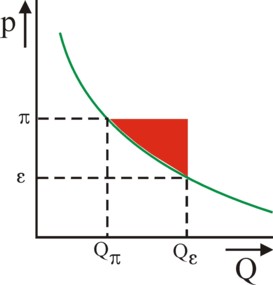

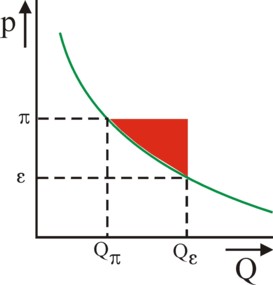

Figure 1: Compensated demand curve

and social welfare loss

The problem of the structure of health care is described, notably the adverse selection and the moral hazard. Next the optimal size of the state budget is studied. Empirical time series of the state ratio are presented. Various factors increase the ratio. The law of Wagner and the Baumol effect are explained. It is also explained, that various social groups are rent-seeking. This is true for citizens, politicians and the state bureaucracy.

Recently the Gazette has studied various important state activities. First the general theory of the social security was explained. Such public services are the pillars of the welfare state. Next the principles of the pension system and social benefits were presented. Recently the primary, secondary and higher education have also been studied. In this series a description of health care is still missing, and the present column fills this lacuna. For the contents the books The economics of the welfare state (in short EW), Economics of the public sector (in short EP), De architectuur van de welvaartsstaat opnieuw bekeken (in short AW), and Öffentliche Finanzen in der Demokratie (in short OF) have been consulted1.

Health care supplies medical services to individuals, aiming to prevent and cure illness. In this column this is succinctly called care, and emphatically here various forms of social assistance (youth care, family care and the like) are excluded. In principle care is not a public good, because it is supplied for individual consumption. In this regard it can be compared to education. Nevertheless, care has various positive external effects. Some care reduces the risk of contagious diseases (p.264 in EW). And care keeps individuals productive, which furthers the national activities (EW 265). Empathy can bring about, that people want to help sick persons in general (EW 264). The state can use such arguments for justifying interventions in the market for care.

The insurance of the costs of health care is unavoidable, because only wealthy people can pay them by themselves. Care can be provided by means of private markets. Therefore in this column the patient is called a customer. The insurer uses the actuarial method for calculating the costs (contribution) for the insurance (policy). The actuarial method has the advantage, that each customer buys the policy, which matches his needs. The health care in the United States of America (in short USA) is based on this method, albeit with various exceptions (EW 262, 273)2. The necessity to insure the costs for care is an important cause for the problems on the market for care. For instance, chronical diseases can not be insured, because the future costs are already known. Since most ill persons can not cover these costs, the state must subsidize them (EW 268; OF 441, 444). Perforce the state intervenes in care.

Individuals can be divided in "good" (profitable) and "bad" (loss making) risks, dependent on their health. When an insurance for the costs of health care is effected, the customers are tempted to conceal their physical deficits. Therefore the insurer misses information. This phenomenon is called adverse selection. Adverse selection has as its consequence, that the private market fails. For, the insurer is not capable of differentiating the height of the individual contributions in accordance with the expected future costs. The economist C.B. Blankart has invented a solution for this. The starting point is, that each insurer calculates a contribution, which is based on the risks of the population as a whole. The insurer maintains a customer file, which describes the health history of each customer (OF 440).

Now, according as the real risks of the customer become clear, the insurer reserves a fund for covering the expected costs of sickness for this customer (OF 446 and further). The funds of the "bad" risks are covered by those, who turn out to be a "good" risk. However, private markets require, that the customer is free to choose his supplier. And now an individual with a "bad" risk kan not simply change to another insurer, because his present contribution does not cover the costs. Since the risk is known, the new insurer wants to calculate a higher contribution. This policy, where the insurers only accept healthy individuals as their customer (or at least the profitable ones), is called cream skimming (EP 318).

Blankart proposes to solve this by coupling the customer to his reservation fund. When a customer changes to another insurer, he can take along his reservation fund with him to the new supplier (OF 448). Then the contribution can remain the same. In this manner the private market can yet survive. The "good" risks kan simply change to another supplier with a lower contribution. Thus the reservation funds are paid mainly by the younger insured customers, who still have a clean file. Incidentally, in all existing health care systems the younger customers pay for the expenditures of the old ones (OF 446). Nevertheless, when your columnist understands Blankart well, this system of transferable reservation funds has never been tried in practice. Therefore the practical results are unknown. According to the economist J.E. Stiglitz the customer file significantly raises the transaction costs3.

Many states prefer a health care system, which makes the inclusion of certain treatments in the insured package compulsory (OF 440). The insurer must offer this package in a policy with a uniform contribution, without differentiation (OF 449 and further). This universal system is not optimal, because it forces healthy individuals (the "good" risks) to have an excessive insurance (OF 451). This incites individuals to omit their insurance. Therefore the state dictates this as an obligation (OF 446). For, it is morally unacceptable to refuse to supply health care to the uninsured individuals. Thanks to the obliged insurance free riding is prevented (OF 446). The state can compensate insurers, which have an excessive number of "bad" risks among their customers, for this (OF 450).

A variant of the fixed contribution is the income-dependent contribution (OF 453 and further). Then the state usually collects the contributions, and pays the insurers from this fund. When care is paid out of the yield of taxes, then the contribution is actually also dependent on income4. In such situations the care system is used to redistribute incomes, albeit in kind. Strictly speaking this is not desirable, because it further weakens the relation between needs and payment (the principle of benefit). However, the economist N. Barr believes, that redistribution in kind is advantageous, in comparison with a redistribution in money. For, then the hurt citizens (those who contribute) can be sure, that their money is indeed spent for improving the health of their fellow-men. This can be a mental reward for them (EW 265). On the other hand, such a redistribution is rather paternalistic.

A problem in care is de situation, where the customer can change the probability of the risk or the incidental loss, for the benefit of himself. This is called a moral hazard (opportunism). An example is the lost wage due to a planned pregnancy. Indeed in the age category between 20 and 45 years the costs for care are much higher for women than for men (OF 454). Yet they both pay the same contribution. Incidentally, the moral hazard created by the customer is limited, because he is not a good judge of his own needs for care (EW 257, 263, 267, 287; EP 309; OF 440)5. Unfortunately this faulty knowledge also implies, that the customer does not really know his own preferences. Therefore the demand on the market is actually dictated by the supply (OF 440).

Nowadays the need of the customer for information is recognized by the state, and he tries to make the market more transparent by spreading information about the suppliers (EW 259; EP 309; OF 443). This is an important improvement. The state naturally also supervises the offered quality, and regulates it. This all reinforces the position of the customer. But yet the customer remains dependent on the physician, who advises him and sells his services (OF 440). The relation is more based on trust than on a market exchange6. Since the physician is often paid for his performance, he is inclined to push the supply upwards (EP 320; OF 441, 454; AW 421). The physician will intervene medically more often than is necessary. It is of course possible to reward the physician with a fixed wage, but this would reduce the incentive to perform7.

The need to cover the costs for care with an insurance reinforces the moral hazard. For, then the insurer pays as the third party in the transaction8. The customer loses the incentive to check the offer of the physician. For, an unnecessary treatment will hardly raise the contribution. The physician and his customer both tend to engage in over-production of care (EW 258, 267; EP 311, 314; OF 441)9. The over-production and -consumption of care reduce welfare, because the customer does not really want to pay for it. Insurers try to temper the over-consumption by asking a personal contribution of the customer for each treatment, or by giving no-claim reductions (EW 276; EP 306, 315, 319).

The figure 1 shows in green the compensated demand curve p(Q) of the customer. It represents the value p, which the customer attaches to an extra unit of care, when he has already received a quantity Q of care. Suppose the total product price is π and the personal contribution is ε, with ε<π. In this case the personal contribution leads to an increase of the consumer-surplus, but the costs for society are larger (EP 315). The red area in the figure 1 is the social welfare loss due to the (small) personal contribution10.

The state combats the moral hazard by imposing an upper boundary on the budget of health care (EP 276; OF 454)11. However, the politicians are pressurized by interest groups, which want to raise the budget (OF 461). They are rent seeking. It turns out that in this manner the costs for care become uncontrollable, at least as long as politics intensely interferes with the execution. The general interest is lost in the struggle for individual interests. Therefore, since the start of the eighties of the last century there is a search for other forms of organization in care (and incidentally also in various other policy fields)12.

The preceding text has shown that care is exchanged on the market. However, each market has its own peculiarities. The problems on the market for care are also found on other markets, but not with the same intensity. The regulation of the market for care, partly by the state, is inevitable. The intervention changes the interaction between demand and supply. The intervention is rigorous to such an extent, that the term quasi-markt is used. This constructed market aims to increase the efficiency of the supply, notably by means of competition (EW 287). The demand on the quasi-market partially originates from public funds (EW 287). However, demand and supply are separated, and decentralized whenever this is possible. The customers can themselves determine their supplier. This system has some similarity with the distribution of consumption vouchers (EW 287).

Competition in health care can be created by various constructions, both in the health insurance and the medical treatment. A way to curb the moral hazard is the integration of the insurer and the physician (EW 168). For, the physician-insurer must keep the contribution low in order to remain competitive. The physician-insurer does create the moral hazard of reducing the quality of the supply (EP 323). Nevertheless, this solution has been chosen in the USA. The English reform of health care since 1991 has also created room for such organizations13.

This paragraph again consults the books, mentioned in the previous paragraph. Besides, knowledge is obtained from Économie et finances publiques (in short EF), Public choice III (in short PC), and Political economy in macroeconomics (in short PE)14.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the industrial proletariat became discontented with its living conditions. The free markets of unbridled capitalism undermined the social well-being. The discontent was expressed in collective ideologies, such as socialism and the christian democracy. They wanted to control the economy by means of the state, possibly together with social organizations, in corporatism. Thanks to deliberations and planning an optimal economic order, which takes rational decisions based on facts, could perhaps be realized. However, during the twentieth century the experiences with state planning were disappointing (EF 222, 392)15. Apparently the unbridled expansion of the state and other collective organizations is not the solution to the complaints about private markets. Therefore in the last quarter of the twentieth century the question rose: what is the optimal size of the state?

Before elaborating on this question, a measure for the size of the state must be defined. Let G be the size of the state expenditures and Y the size of the gross domestic product. A useful measure is the state ratio, which is defined as γ=G/Y (OF 150; EF 437). The variable G also includes the transfers O by the state, such as subsidies and benefits16. When these are excluded, then one finds the real state quote ρ = (G-O) / Y (OF 150). The values of G and Y can be calculated by means of the market prices of products and services. Here a problem is, that many public goods do not have a market price. Therefore the value of G is commonly calculated by means of the factor costs. This is the sum of all rewards for the production factors (labour, capital, land), which are needed for the production of the public goods. Generally the calculation of the private production Y − G does use the market prices (OF 150)17.

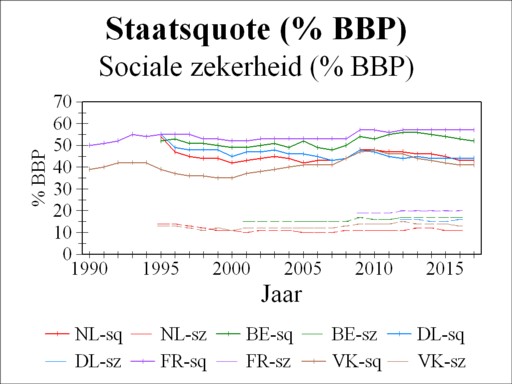

The figure 2 shows time series of the state ratio γ for the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom18. In the considered period 1990-2017 the values of γ are between 35% and 57%. The graphs show, that some states prefer a clearly larger size of the state than others. Apparently this is determined by the development of the national institutions. There is a path dependency, which merely allows for limited fluctuations of γ (EF 227). For instance the Belgian and French corporatism lead to a high state ratio (AW 441). Also take notice of the increased state expenditures since 2008, which aim to combat the consequences of the financial crisis and the following crisis of national debt. In the graphs this is only apparent as a ripple. The United Kingdom has relatively the strongest intervention, but also here the old level has been attained in 2017.

The figure 2 also shows the size of the social security Z (as dashed graphs), with the exclusion of the transfers in kind. These data for the same five mentioned states also originate from Eurostat. The values of Z/Y vary between 10% and 20%. Also here the largest differences occur when comparing states, and not in the time series of the separate state. For each state Z/Y is almost constant for the considered period, except for a ripple around 2008. The social security is also strongly determined by the institutions, and can not simply be changed. The difference (G-Z)/Y has values between 30% and 35%. Since there are various other transfers, also in kind, the real state ratio ρ is less. The German ρ is merely 13% in 2009 (OF 153)19. In any case it can not be concluded from the figure 2, that the transfers evolve differently than the production of public goods.

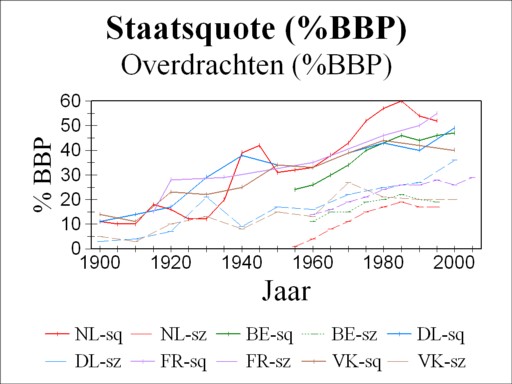

The social institutions evolve quite slowly. A period of a quarter of a century, such as in the figure 2, is too short for studying the national evolution. Therefore the figure 3 shows the same variables γ and Z/Y (or a similar transfer) for a longer period, namely a century (1900-2005). Such time series can not be found at Eurostat or the OECD, so that your columnist had to consult his own sources. Unfortunately each of these sources only gives the time series for a single state. Therefore the figure 3 gives a reliable picture of the development in time for each state, but not the differences between the states20. The essence of the figure 3 is, that during a century a big change occurs for each state. The institutions radically change. Notably during the First and Second Worldwar the state ratio expands significantly. Between 1960 and 1980 there is again growth, followed by a stabilization21.

The figure 3 illustrates, that a state ratio of 35% or (much) more is not strictly necessary. Moreover, the experiences of the Soviet Union have shown, that a state ratio of 100% slows down economic growth. It is generally assumed, that there is an optimal value of γ, where the economic growth gY peaks ("inverted U form": EF 455; PC 549 and further)22. However, the optimal γ could differ for poor and rich states (PC 550). Politics must carefully search for the optimal size of the state. In the figure 3 the various transfers have about the same growth rate as the state ratio of the concerned state. Apparently both the need for public goods and for transfers increases. But a large state also has disadvantages (EF 435). For, the state imposes various contributions on its citizens. Thus the citizens can no longer freely and at will dispose of their income, for instance for economic activities.

Science gives insight in the optimal size of the state. Notably, much research has been done on the causes, which have led to the continuous growth of the state. When the causes of this growth are understood well, then the less desirable growth factors can be suppressed, so that the damage to the economic performance can be reduced, and the optimum is approached more closely. The present paragraph sums up a number of growth factors. The starting point is that G is a function of the income Y, the size N of the population, the national preference U for public goods, and the price τ of the public goods (OF 161; PC 507; PE 680). However, egoistic motives for obtaining rents can also make the state grow. In the past years the Gazette has regularly paid attention to such behaviour, based on self-interest. It is sometimes difficult to clearly distinguish between the group interest and the commonly shared preferences.

Already in 1876 the German economist Adolph Wagner predicted, that the state will grow faster than the economy (OF 141; EF 439)23. According as the citizens become more wealthy, their need for collective goods rises, such as infrastructure and regulations. The social security also is an indispensable part of industrialization (PC 508). It is a luxury good (EF 439). In a broader sense redistribution can be interpreted as a part of social security (PC 507, 530). Your columnist believes that the law of Wagner is credible. Expressed as a formula the law implies, that the elasticity of income of the state size satisfies εYG = (∂G/∂Y) / (G/Y) > 1. According to some economists this is indeed the case (EF 215, 439), but others believe that nowadays one approximately has εYG = 1 (OF 162; PC 509; PE 680). When the latter group is right, then the demand no longer justifies a rapid state expansion. Incidentally, even with a stable size G the state can always shift between policy fields.

The value of εYG gives no information about causality. Not all G is a luxuy good. Wagner already suggests, that the state (G) may be a production factor (EF 440). For instance, education, health care, infrastructure and scientific research raise the labour productivity (EF 393, 449-450). Markets can benefit from the constitutional state and from various institutions (EF 451; PC 546). It has been suggested, that the expanding branches of services prosper thanks to state interventions, because these reduce the transaction costs (PC 522). Regulation curbs the natural monopolies, and restricts competition, for instance in order to eliminate negative externalities (EF 229; PC 506; PE 678). And redistribution furthers the social cohesion and political stability (EF 452; PC 546). It has an added value for the citizens (PC 516). Then the citizens will increase G, until the marginal product ∂Y/∂G equals the marginal costs τ of the public goods.

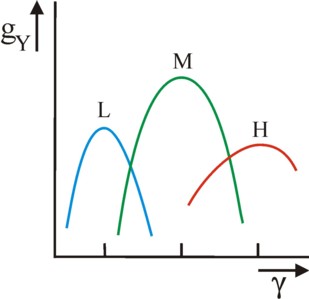

Recently, globalization affects G. On the one hand, the global competition enforces low taxes, in order to keep the prices of the export products low (OF 174)24. On the other hand, globalization requires a lot of regulation (EF 216). And it increases the economic uncertainty, because a deficit on the balance of payments can emerge due to the worsened terms of trade (PC 507). Subsequently this global conjuncture must be moderated by means of the social security (OF 174; EF 444; PC 508). It turns out empirically, that open economies with trade risks have indeed a relatively high state ratio (PC 507). Especially corporatist states are attached to income security (OF 174). This suggests, that the value of γ with an optimal economic growth gY differs for each type of state. The figure 4 distinguishes between lowly, moderately and highly developed states, and shows that a rising development leads to a higher optimal state ratio (PC 549-550)25.

Thus the law of Wagner has a productive and a consumptive side. The production Y requires a state G. But the citizens themselves also need G. In the end, in a democracy the voters determine the size G of the state (EF 456). The electorat is sometimes divided in the underclass, the middle class and the upper class. Generally, the underclass prefers a lot of G, and the upper class wants to restrict G. The median voter determines the standpoint of the majority (OF 118; EF 212; PC 514). Thus the middle class has a key position, because it can choose between coalitions with the underclass and the upper class (PC 515, 519). This model of the median voter reminds of the MAR theory of the social psychologist Mauk Mulder.

The size of the state is partly determined by the price elasticity of the public goods, namely ετG = (∂G/∂τ) / (G/τ). Here the price τ is somewhat artificial, because generally public goods are not supplied by the private market. The tax rate must be interpreted as a price. When G is measured physically (say, in units), then obviously ετG is negative (PC 507). Nonetheless, when ετG lies between -1 and 0, then the state ratio (in money) will rise with a rising price τ (EF 442; PC 507). The reason is, that G in the state ration is expressed as a monetary sum, and therefore includes τ. It turns out empirically, that |ετG| is (physically) probably indeed less than 1 (PC 510, 511). This conclusion leads to the so-called Baumol effect, also called the cost disease of Baumol (OF 163; EF 226, 441; PC 510; PE 680).

The economist W.J. Baumol remarks, that the price τ is determined in part by the labour productivity ap in the public sector. This ap rises slower than the productivity in the industry, because the public sector mainly produces services. It is difficult to automate services. Therefore the price level of public goods rises faster than the general price level (price index). It has just been stated, that this leads to a rising state ratio γ, because the demand rises inelastically. Note that the Baumol effect pertains specifically to the productive activities of the state, and not to the transfers. Transfers hardly require any production. So the Baumol effect can not explain the rise of the transfers (OF 163; EF 442; PC 511).

The Baumol effect can give cause for dramatic reflections about the future G 26. Fortunately, there are various factors, which weaken the Baumol effect. First, the labour productivity in the public sector can be improved, thanks to the information- and communication-technology (OF 163; PC 510). Furthermore, the private sector also increasingly produces services, and this affects the general price index (OF 163; EF 226; PC 510). Nonetheless, empirical studies suggest, that within the OECD the Baumol effect is indeed important (PC 510, 530)27.

The law of Wagner and the Baumol effect are causes of state growth, which are legitimate, wanted or unavoidable. The citizens appreciate a fairly strong state. But this can not explain all growth. The remainder of this paragraph discusses causes, where the various social groups use state growth as an instrument for personal rent seeking. obviously interest groups can be socially useful. The communitarianism argues, that such groups order the individual egoism and impose duties on their members, and further participation. The interest groups can be a form of social capital. In a pluralistic society the interest groups can be indispensable links in the social networks. They seek justice, but not rent.

But interest groups can also be the cause of injustice and stagnation. This is called institutional sclerosis (PC 556). Too much capital can be wasted in an unproductive lobby. Sometimes the state does not establish the right framework for the struggle between interests, and then a powerful group can be parasitic on the rest of society. This is undesirable, and in fact a case of administrative failure28. Naturally these interest groups prefer to receive their interest in the form of subsidies. However, this might attract the attention of the media and other groups. Therefore the interest groups often strive for transfers in kind, which are less conspicuous (OF 168; EF 211; PE 680-682). When they succeed in their intention, then the state ratio is unjustly raised. According to the economist Olson such interest groups will finally change into institutions (OF 169; PC 555). The corporatism is pre-eminently amenable to such abuses (OF 169).

The state ratio is determined by the national legislator, and therefore by politicians (EF 225). The politicians are elected by the citizens in periodical elections. Thus the national electoral system affects the state ratio (OF 154; PE 683). The political decisions follow the preferences of the citizens (OF 160). The median voter is leading. However, the politicians also seek rent for themselves (OF 166; EF 211). Politicians want to be elected, gain power, and promote their ideology (EF 212). They benefit from favouring certain groups in their rank-and-file. Therefore politicians promise, among others, transfers to these groups (PE 681). Such transfers are not necessarily in the general interest, and then there is over-production. Politicians can do this for tactical-electoral reasons, even when they are of good will.

A well-tried means is the engagement in coalitions with other politicians, which is based on a mutual support of each other's interests. Such occasional coalitions are called logrolling (OF 166-167; EF 444; PC 532). The costs of the exchange of favours is shifted to the minority outside of the coalitions, so that society can yet be hurt. For instance, the state ratio is increased without any need (OF 167). However, exchanging votes also has advantages. In this manner a minority can still satisfy its intensely felt needs, simply by effecting their realization by means of an exchange for less pressing concessions (EF 210). Then logrolling leads to more stability in the balance of power between the various groups (PC 532)29.

According to the political scientist W.D. Nordhaus, a political conjuncture can emerge, because the ruling politicans spend extra money immediately before the election (OF 172; PC 528; PE 228 and further). Later this returns as taxes, due to the national debt. Forthcoming elections make politicians myopic (EF 215)30. Furthermore, when the ruling politicians fear, that they will lose the elections, then they can spend extra money in order to thwart their successors31. The politicians obviously need funds in order to pay the rent for their rank-and-file. This requires unnecessarily high taxes. However, the tax system is complex to such an extent, that the voters underestimate the size of their liabilities. The economist A. Puviani was the first to discuss this phenomenon, which is called the fiscal illusion (OF 172; EF 442; PC 527, 531; PE686). For instance, the voters often do not understand the creeping increase due to the progression in the tax rates (PC 528).

It has just been remarked, that high taxes T hurt the exports, and limit the freedom of consumers. Furthermore, marginal changes of the taxes (this is to say, marginal increases or reductions ΔT) affect the individual behaviour (PC 536). The column about welfare economics has shown, that rising taxes cause a dead-weight loss (DWL) in consumption. In a similar way, higher taxes can discourage working, because they lower the freely disposable wage (PC 539). There exists much literature about the optimal level of taxes, which will minimize the distortion of behaviour. However, this subject oversteps the theme of the present column. In the future the Gazette will yet address it32.

In the discussion of the law of Wagner it has been remarked, that politicians can offer public goods in order to pacify social groups (OF 170). Sometimes this has social advantages, but it can also be an expression of political laziness33. A political system with direct democracy (referenda) between two elections probably reduces the rent seeking of politicians (OF 161, 173, 175; PC 531). For, between two elections the citizens can enforce their will by means of referenda, and for instance block an increase of the state ratio γ. Switzerland is commonly mentioned as the textbook case of the favourable effect of the direct democracy. In general decentralization reduces the growth of γ (PC 533).

During the seventies of the last century the political scientist A. Wildavsky pointed out, that the bureaucracy of the state disposes of a monopoly position (OF 170)34. Another economist, W.A. Niskanen, states that therefore politics can not simply dictate its will to the bureaucracy (OF 134, 170; EF 446; PC 362-368; PE 688). The politicians must supervise the execution of their policy, but they have less information and skills than the bureaucracy (OF 171; EF 219; PC 525). The bureaucracy strives for more income, power and expansion (EF 219; PC 362, 523-524). This leads to the over-production of collective goods. Thus it pushes up the state ratio (OF 171). Previously the Gazette has already presented a model of the state bureaucracy, in the column about collective property, which illustrates the over-production. When the bureaucracy forces up the wages of the civil servants, then this is called X-inefficiency (EF 221; PC 362).

The well-known economist J.M. Buchanan has, together with G. Brennan, developed the Leviathan model of the state (EF 447; PC 380-383, 529-30). In this model the politicians and the bureaucracy are presented as a coalition, with a collective interest. Then the politicians are no longer the supervisors of the execution. This changes the nature of the principal-agent dilemma. The citizens are still confronted with rent seeking politicians, but now these are backed by the power of the bureaucracy. In this (admitted, quite grim) situation the citizens can only control their politicians by means of the constitution (PC 380-381)35.

For many years your columnist has been active in politics, as a party militant. Rent seeking by citizens, politicians and bureaucrats, can be observed in practice. This conclusion is nothing new, because of old the traditional religions and psychology warn against the "sinful" human nature. The awareness of the earthly "brokenness" belongs to a virtuous image of man36. However, thanks to new institutional economics (NIE) and the public choice paradigm, knowledge about the mechanism of rent seeking is now available. This has the advantage, that policies can take into account such undesirable behaviour. Thus the state ratio γ can indeed be brought closer to its optimal level.

| state | 1913 | 1920 | 1937 | 1960 | 1980 | 1990 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL | 9 | 14 | 19 | 34 | 56 | 54 | 49 |

| BE | 14 | 22 | 22 | 30 | 58 | 54 | 53 |

| DL | 15 | 25 | 34 | 32 | 48 | 45 | 49 |

| FR | 17 | 28 | 29 | 35 | 46 | 50 | 55 |

| VK | 13 | 26 | 30 | 32 | 43 | 40 | 43 |

| state | 1937 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL | - | 12 | 29 | 39 | 36 |

| BE | - | 13 | 21 | 30 | 29 |

| DL | 7 | 14 | 13 | 17 | 19 |

| FR | 7 | 11 | 21 | 25 | 30 |

| VK | 10 | 9 | 15 | 20 | 24 |