Figure 1: Button Rietkerk

(AbvaKabo FNV)

During the cabinets Lubbers and Kok the Dutch economy has recovered miraculously. The present column studies the executed policies of these cabinets, by means of the book A Dutch miracle. It turns out, that corporatism or pluralism was preferred, depending on the policy field. The criticism of the policies is also analyzed. Balkenende and Fortuyn want to replace the corporatism by pluralism, possibly on an organic basis.

In a previous column it has been described how since 1982 the Dutch economy has recovered thanks to a package of reforms. Notably the economic growth increased again, the collective expenditures were reduced, and the participation on the labour market has increased significantly. The present column elaborates on the nature of the various reforms. Despite the good results there is yet also criticism on the then executed policies. Here the criticism will be discussed extensively. Special attention will be paid to the ideas of the writer W.S.P. Fortuyn, because he created a shock in Dutch politics, with lasting consequences. The criticism itself naturally again incites comments, but these are banned to the footnotes, whenever possible.

The present description of the Dutch package of reforms is mainly based on the authoritative book A Dutch miracle (in short DM)1. This book exculsively focuses on reforms, which occur in three policy fields, namely (1) the industrial relations, (2) the social security, and (3) the employment exchange. It is immediately admitted, that this focus is rather restricted. For instance, nothing is said about the whole package of reforms, which aimed at the efficiency of the public sector and of the administration. This package reinforces the supply side of the economy. The regulation and the state interventions have been reduced, so that free markets again can return. In the public sector organizations often receive some autonomy, or they are privatized. The state policy also increases the use of human incentives, such as the principle of benefit (those who benefit, contribute)2.

Neither is attention paid to the significant investments in Dutch infrastructure by the Purple cabinets. In short, the book does not sketch a complete picture, but merely the developments in the mentioned three policy fields. Reforms are possible in favourable periods, when the institutions, politics and the relations of power all operate in the same direction (p.12 in DM). The recession of 1982 created a sense of urgency (p.99). There is a social learning process3. The reform package consists of three phases, corresponding to the three policy fields. In pahse 1 (1982) the profit rate in the industries is improved. This is accompanied by wage moderation. Phase 2 (1992) is the reform of the social security. In phase 3 (1995) the labour market is reformed. The social debate concerns respectively the industrial and social rights, and the right to work.

The reforms are a package, because they reinforce each other (p.16). The reforms require social support. The book notably elaborates on the various roles of corporatism, that is to say, the cooperation of the trade union movement and the associations of entrepreneurs. The institutional time path of corporatism is capricious. After the Second Worldwar it is made formal in the Foundation of Labour. But around 1970 this institute becomes outdated (p.96). In 1982 it is again revived with the signing of a Social Pact (concluded in Wassenaar; phase 1). After 1989 there is an increasing support for the reform of phase 2, when the number of disabled workers rises to 17% of the professional population (p.18). This reform is completed thanks to the resolute political leaders (Lubbers and Kok), although the trade union movement protests4. The phase 3 is again in the form of corporatism.

In other words, the phases 1 and 3 have been completed in an atmosphere of consensus, where the interests are reconciled by means of compromises ("voice"). The institutions are adapted in a process of mutual trust. On the other hand, the phase 2 is pluralistic (p.53). There is a conflict, where the interest groups prefer the "exit", and in the end politics wins. Here the trade union movement refuses to be a part of the learning process. The development of the European Union in the Treaty of Maastricht is an external factor of influence in the willingness to reform (p.64)5. All in all, the Dutch time path shows an inclination to prefer corporatism, partly due to the christian tradition. The state is prepared to share the tasks of public law with the civil society (p.66). The phase 2 illustrates, that in such a system the exit costs are high for all involved groups.

Politicians try to realize the right mix of market, civil society, and state. The benefits of the formation of consensus are known to the loyal reader. The involved groups succeed in defining a general interest, because they share the same morals. Mutual obligations reduce the transaction costs, increase the time horizon, and reinforce the network. The regulation becomes self-enforcing. There is more symmetry of information. This all stimulates the learning capacity of the various groups and circles In pluralism, which is found in particular in the Anglo-saxon system, these virtues are all weaker (p.69). On the other hand, corporatism has disadvantages, notably when the conflict becomes more severe. Such a situation of politization can degenerate into a decision trap (p.75). Then the state is better off by using pluralism. Thanks to pluralism, it can act relatively rapidly and energetically, because it is free of impasses6.

The choice for corporatism or pluralism is ultimately determined by the specific situation and the policy field (in casu: a corporatist phase 1&3, and a pluralistic phase 2). It turned out that the corporatist institutions were sufficiently flexible to adapt for the case of wage moderation and the employment exchange (p.74). It did not succeed for the case of the social security7. Visser and Hemerijck, the authors of A Dutch miracle, prefer the corporatist method, because then the reforms can rely on sufficient support, and proceed by means of a gradual adaptation (p.79). For instance, the wage moderation and the flexibility of the working hours (the industrial relations) are realized in corporatism, which continues until the present (p.111). Corporatism even shifts to the micro level of the enterprises8.

In the case of the social security the cabinets Lubbers first try to maintain corporatism, partly because they do not want to endanger the wage moderation (p.144). The retrenchment of the social benefits uses the method of decremental slicing (p.135). This leads to a gradual stabilization of the benefits during the economic hausse, but in 1990 these expenditures again begin to rise. And the economic growth is almost jobless. Due to the high insurance premiums, the gross wages (the wage costs) also remain undesirably high (p.138). Therefore the cabinet Lubbers 3 decides to reform the social security on its own (exit, followed by pluralism). The Purple cabinets continue on this path (p.146). Financial incentives are introduced in the insurances.

Traditionally, the Netherlands has never applied an active policy on the labour market. The desire to reform the employment exchange grows gradually, among others due to the high unemployment around 1982. This is done primarily by means of wage moderation. But in 1990 the Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid (scientific council) advocates the stimulation of the degree of participation (p.140, 157). This policy must also address groups, which in the past were not at all available for the labour market, notably women. The passive welfare state creates too much dependency (p.156). In abstract terms: the state must invest in human capital. Concretely, the state can activate by means of training, jobs which increase experience, jobs in the public sector, job pooling, and wage subsidies (p.173-174).

The reform proceeds by means of corporatism. For instance, in 1994 the trade union movement blocks the abolishment of the protection against dismissal (p.162). In this policy field the market has its own role, because since the seventies the commercial temporary employment agencies contribute to the job mediation (p.165). In 1993 there is an experiment with a tripartite board for the employment exchange (p.169). But the social partners (trade union movement and the associations of enterprises) mainly engage in rent seeking. Therefore the public employment exchange is already strongly restricted in 1995. Henceforth it will merely mediate for "vulnerable" groups (p.172)9.

All in all, Visser and Hemerijck believe that the package of reforms and its results truly are a mircale. The reviving of corporatism in 1982 has worked well. The economic growth increased, the employment has been extended, and moreover it has been distributed over more workers (p.29, 180). The wage moderation stimulates the service sector, which fulfills needs and therefore potentially offers much employment. Besides, the reforms have barely affected the income equality10. Dependent on the policy sector, the state has selected corporatism or pluralism. According to Visser and Hemerijck, luck has also played a role in the eventual success of the reforms (p.185). In any case, other states can not simply copy the Dutch solution.

Unfortunately the reforms have not ended the long-term unemployment (p.36). Moreover, there is still a lot of hidden unemployment (jobs with wage subsidies, social benefits, disability, and early retirement) (p.39). Even in 1997 this "wide" unemployment (open and hidden) still affects 20% of the professional population (p.113). This failure leads to criticism, notably by Fortuyn, who states that this situation is inhumane.

Corporatism is related to the christian-democracy. Therefore it is interesting to analyze the views of christian-democratic ideologists with regard to the economic recovery. During the nineties of the last century the politician J.P. Balkenende was active in the Scientific Institute of the CDA. The present paragraph analyzes his view, as far as it concerns the reforms and the resulting economic recovery. Balkenende defends the traditional christian moral, that the society equals a collection of circles, such as families, enterprises, and the civil society (associations and organizations; in the past notably the churches)11. The state and the economic markets must be the servants of the circles, so that their sovereignty is maximal. The private initiative gets primacy, and management must be selfregulation, whenever possible. This is called organic pluralism.

Social organizations must be active in the public sector, namely in education, health care, media, housing and insurances12. They have their own responsibilities, and are paid by their members. In other words, the social responsibility is spread, and the principle of benefit is leading. Such private organizations have the advantage, that they are a reference-point for their members and users13. They create coherence, thanks to their shared morals. The morals must include at least a constitutional patriottism14. In such a structure the state is nothing more than a central supervisor. Therefore Balkenende wants to reduce the "subsidy-state"15. So it is not surprising, that he (just like traditionally the christian-democracy) likes the bipartite structure of deliberations. Incidentally, this fits well with the institutions at the European level16.

Balkenende wants to clearly separate the responsibility of the state and of the social partners (enterprises and trade unions). It makes sense that he advocates to leave the insurances for workers in the hands of the social partners. He even states, that the social partners must also accept responsibility for the environmental protection, employment, and the economically weaker regions. He expects, that such a self-regulation furthers the growth dynamics17. This gives the impression that he agrees with the argument of Visser and Hemerijck. Nevertheless, Balkenende clearly wants to place the state at a greater distance. He sympathizes with the bipartite structure. He prefers a different form of organization, namely civil law instead of public law. Autonomous associations and organizations will compete more with each other. Balkenende shows, that there is a real alternative for the Purple policy.

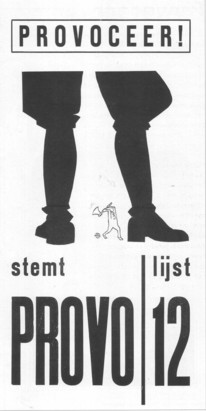

The previous column has shown, that the Dutch miracle lasts until the financial crisis of 2008. However, yet the citizens become discontent, because in the elections of 2002 the Purple cabinet Kok 2 loses. The just founded Lijst Pim Fortuyn gains 17% of the votes. Since according to Fortuyn the Purple cabinets have created a disabled state, it is interesting to analyze his criticism. Here his books are consulted, notably Zonder ambtenaren (in short ZA), Uw baan staat op de tocht! (BT), De verweesde samenleving (VS), and Mijn collega komt zo bij u (CU)18. An additional argument for this paragraph is, that not everybody shares the enthusiasm of Visser and Hemerijck for corporatism. There is also much support for pluralism, and precisely Fortuyn gives this a warm recommendation.

It is already now remarked, that the ideological argument of Fortuyn is rather radical and unsound. Readers, who prefer discussions with nuances, can skip this paragraph with an easy mind. Fortuyn begins his career as a teacher in marxist theory, in 1972. He remains employed with the university of Groningen for 16 years. Soon his focus shifts to the policy of the labour market. After 1988 he becomes a true liberal. After 1995 he develops his own philosophy of morals, which is the foundation for his electoral successes in 2002. Thus it is difficult to place Fortuyn in an ideological category, certainly for your columnist, who derives his pleasure from socio-economic themes19. His philosopy of morals is roughly as follows.

People unfold in groups. The group or circle cherishes collective morals, which give meaning to the existence of their members. Fortuyn believes that in modernism the morals do not grow spontaneously any more, but must be constructed in a conscious manner (p.67 in BT, p.128, 223-225 in VS). It seems logical to choose a constitutional patriottism, but apparently this is not enough. He is convinced, that morals must be spread by the leaders of the group. Incidentally, this view is controversial20. He distinguishes between two functions of the leader. First, there is the Father, who formulates the group laws, and supervises them (p.160, 213 in VS). Second, there is the Mother, who creates bonding and cohesion. A single person can occupy both functions21. The relation of the ideal leader with his rank-and-file corresponds to the master and his pupils. The leader is the innovator, and the pupils imitate him. He is the sheperd (p.237 in VS).

That is to say, the leaders do not negotiate with their rank-and-file, but impose their will. This process occurs with a minimum of coercion22. This philosophy of morals of Fortuyn sounds paternalistic, and is difficult to reconcile with the modern need of personal autonomy. Yet the criticism of Fortuyn with regard to his political opponents (say, the ruling elite) is, that they do not understand the logic of his argument. He creates a conflict about the political morals. He rejects the existing policy, because in his eyes it is technocratic. This is the result of the de-pillarization, which has eliminated the morals23. A state without Fathers can not survive in the global competition, and will perish. In this view there is naturally not a miraculous recovery. On the contrary, during the past decades the Dutch institutions have completely been derailed24.

Although Fortuyn, with his liberal ideology, can agree with the policy of deregulation and privatization, he believes that the recent reforms are not sufficiently radical. All in all, the technocrats (experts, professionals) have preserved their power. This is not democratic, because they are not interested in the needs of the citizens. The general interest is ignored (p.92 in ZA). Therefore, Fortuyn wants to reform the social structure in such a way, that in all administrative positions the Fathers again return to power. It would seem, that this will create a strict hierarchy. However, Fortuyn understands, that the citizens have emancipated thanks to the (counter-)culture revolution of the late sixties25. He wants to increase the freedom of the calculating citizen26. Apparently he believes, that the group leader (Father) will propagate such morals, that his rank-and-file will agree completely. Balkenende also has this conviction.

Apparently the criticism of Fortuyn does not primarily concern the socio-economic domain. Nonetheless, his publications in the period 1990-1995 contain interesting studies about this, with a liberal tone. He appreciates individualism, flexibility, and small scale (p.12 in BT). In essence, his ideas are a utopian blue-print. He proposes a simple alternative for the administration of the state, which is copied from the big industries. He calls it the modulization (p.34 in BT). The state must shrink considerably, resulting in core ministries, as it were with the size of the head-quarters of a big enterprise (p.27, 51, 79 in ZA). Henceforth the state and politics must restrict their activities to merely the strategic policies, and the supervision of the policy results (p.80 in ZA, p.80 in VS).

The execution is put out to contract to private organizations, whenever possible27. This creates room for self-organization and -regulation, so that policies can be made to measure (p.80 in VS). A true entrepreneurship results (p.56 in ZA), and the organizations become smaller. In other words, the human scale must return in the policies (p.122 in VS). For, in large groups there is anonimity, and this leads to egocentrism among its members (p.214 in VS). Moreover, the leaders lose contact with the rank-and-file and with their own group (p.49 in BT, p.220 in VS; incidentally, this latter statement is controversial28). Apparently, here Fortuyn embraces the organic pluralism, which at the time was also propagated by the CDA. However, he does this in such a radical manner (again), that the approach loses its logic29.

Fortuyn makes several proposals for the three policy fields of Visser and Hemerijck, namely the industrial relations, the social security and the employment exchange. He resolutely promotes pluralism, and does not appreciate corporatism. The desired small scale fits poorly with collective arrangements (p.21 in BT). Fortuyn is convinced, that the tripartite system (the Rhineland model) will disappear (p.31, 50 in BT, p.89 in VS). Nowadays there is insufficient support for delibarations in the economy.

Just like Balkenende, Fortuyn also wants to separate the state and the civil society (p.10, 77 in ZA, p.220 in VS). Then the various associations of the social partners simply become pressure groups (p.96 in ZA, p.52 in BT). They will have to prove their utility (p.62 in BT). The trade union movement loses tasks to the works council (p.96 in ZA). The consensus must be replaced by power and countervailing power (p.83 in ZA). This creates room for new groups and outsiders (p.83 in ZA). The social partners can naturally of their own free will and unanimously choose an organic system with a bipartite structure, like Balkenende propagates, but that is not absolutely necessary.

Since Fortuyn prefers policies made to measure, he rejects a collective wage moderation. Nowadays, collective agreements make the labour market rigid, which impedes the entrance of unemployed (p.29, 31 in BT). The deliberations with the trade unions must be decentralized (p.89 in ZA). He wants a wage level, that adapts to the market demand. The labour market becomes global, and this increases also in the Netherlands the inequality (p.40 in BT). This means that notably the low-paid jobs must become cheaper (p.18 in BT, p.67 in CU). Henceforth the remittance of premiums for the labour insurances become voluntary (p.51 in BT). But the wages of the top jobs must rise, notably in the state (p.27 in ZA). During the eighties the top officials have been underpaid too much(p.71 in ZA)30 More generally, the wage must be coupled to the performance (p.100 in ZA).

Fortuyn takes as his starting point for the social security, that everybody must be able to pay his own living costs (p.18 in BT). Solidarity does not mean the certainty of the income, but of jobs. Jobs give self-respect, status, and contacts (p.19 in BT). He calls the existing system of social security inhumane, because it does not offer a perspective to the receivers of benefits (p.77 in VS). The existence is guaranteed to such an extent, that the receiver is not incited to become active (p.107 in VS). Therefore, Fortuyn wants to transform the social security into a mini system, which focuses on the truly inactive persons (p.51, 68 in BT). The general benefit disappears (p.68 in BT), so that the able unemployed must live from a negative income tax (p.51 in BT). The collective sector must more often apply the principle of benefit (p.35 in CU). Therefore a performance in return may be asked from those persons, that apply for support (p.37 in CU).

The reader will understand, that Fortuyn rejects the tripartite structure of the employment exchange (p.93 in ZA). With regard to the employment exchange he advocates a radical version of the Anglosaxon model. He wants to realize full employment by making the labour market more flexible (p.70 in BT, p.110 in VS). The protection against lay-offs must be restricted fundamentally, so that the workers remain active (p.19 in BT, p.108 in VS). His ideal is that henceforth everybody gets a temporary labour contract (p.68 in BT). The temporary employment agencies are useful, notably for the employment at the bottom side of the labour market (p.36 in BT).

According as the wages are lower, the Dutch economy can become more labour intensive (p.71 in BT). He rejects wage subsidies, and prefers low-paid jobs in the personal services (p.63 in BT). Consider cleaning jobs, day nursery, taxi services, gardening, shopping services, handymen, canteen personnel, porters, and even again the direction servant (p.67-69, 80 in CU)31. Thanks to the new jobs the workers can again form their own networks (p.69 in CU). So although Fortuyn wants to create jobs mainly in the service sector, he yet advocates the maintenance of the Dutch industries (p.108 in ZA). Unfortunately an explanation is missing. Considering the liberalism of Fortuyn, your columnist suspects, that he favours a voluntary wage moderation and flexible jobs for the personnel.

In conclusion: the ideology of Fortuyn created a shockwave in Dutch politics, despite the considerable welfare. Yet his ideology does not contain much truly innovative ideas. His plea for pluralism can at the time also be found with Balkenende and others. The moral philosophy of the Father is conservative and paternalistic. Besides, the radical implementation by Fortuyn, leading to apparent contradictions and utopian blueprints, looks unsound. It is admitted, that a philosopy can never be refuted objectively, because it is in essence a belief and conviction. It is impossible for the case of Leninism, and for the case of Fortuynism as well. Therefore Fortuyn can still convince people. Your columnist concludes with a speculative summary: perhaps Fortuyn prefers an untamed liberalism, where he trusts that the Fathers will at least keep the mini system of social security at a humane level?