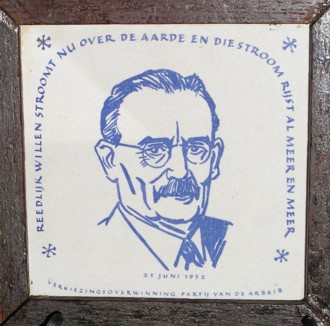

Figure 1: Tile of Willem Drees sr.

This column complements a previous discussion about the public branch-corporations (publiekrechtelijk bedrijfsorgaan, in short PBO) with many annotations, They show that the input of individuals influences the political developments. Among the leaders are J. Veraart, D.U. Stikker, E. Kupers, W. Drees and H. Vos. The position of the trade unions during the German occupation in 1940-1945 is discussed extensively. During this period the Foundation of Labour (Stichting van de Arbeid) is formed. There is also an analysis of the ideas of the social-democracy and the roman-catholics immediately after the liberation. Finally, the opinions of present-day politicians with regard to the PBO are summarized.

Your columnist is definitely stuck on political economics. She engages in a search for universal laws, that are the foundation for the economic actions in society. According as this knowledge increases, the social order can be directed better towards the collective well-being. However, sometimes political economics fails to understand the reality, namely when individuals determine the course of things. In such situations historical studies are indispensable. This is the case for the establishment of the public branch-corporations. For, once one knows the case history, it is surprising that after the Second Worldwar the social-democrats and roman-catholics quickly abandon their ideal of an economic order. In this whole process the behaviour of the leaders of the trade unions is essential. This column tries to sketch a picture of the then personal entanglements.

The Second Worldwar itself brings about, that the traditional patterns are broken. Two causes can be identified, namely the weakening of the ruling authority and the transition to crisis management. With respect to the first cause: it is generally known, that after a war the defeated states are particularly vulnerable to revolutions. The ruling regime has lost its good will, so that alternative groups and avant-gardes get a chance. The change of power van lead to a break with the tradition. Two examples of this phenomenon are the revolutions in Russia and Germany after the First Worldwar. The victor can prevent this by occupying the defeated state, and take over command. But when later the victor withdraws, such as was the case in the Netherlands in 1945, then the question of leadership re-emerges.

With respect to the second cause: a war creates a situation of crisis, which requires a more central form of leadership1. In times of peace the leaders are mainly concerned with the expansion of the support for their policies. Therefore they consult the rank and file by means of participation, which usually is cast in an institutionalized form. Such a policy is continuous and predictable, because the individual preferences are equilibrated. The law of the large numbers is valid, and the average preference in the distribution of Quetelet can persevere. However, in times of crisis a rapid and energetic reaction is required, and then participation becomes subordinate. Therefore the organization gives a mandate to her leaders in order to decide in the name of their ranke and file. Then the personal preferences of the leaders get obviously more chances to persevere. Therefore the policies become less predictable.

In uncertain and chaotic situations people tend to be seduced into behaving in an opportunistic manner. They do not conform to the expectations, that others had of them. Yet one must be reticent with criticism, remembering that "he who is without sin, cast the first stone". Your columnist is not willing to do that. Nevertheless it is instructive to analyze such situations, and to learn lessons from them. This is the purpose of the present paragraph. It describes some personal relations within the leadership of the Dutch trade unions during the Second Worldwar. The relations have unmistakably influenced the structure, that was chosen for the collective bargaining between the social partners (who at the time are often called the industrial companions) after the Second Worldwar.

At the beginning of the war there are three large federations of unions in the Netherlands, with each several hundreds of thousands members, namely the Dutch Associations of trade unions (Nederlands Verbond van Vakverenigingen, NVV), the Roman-catholic worker's association (Rooms-Katholiek Werklieden Verbond, RKWV), and the Christian national trade association (Christelijk Nationaal Vakverbond, CNV)2. Besides, there is a handful of federations with various ideologies, with each several tens of thousands members. After the defeat of the Netherlands the German occupier comes into power. He assigns several important positions to members of the congenial party National-socialist movement (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB) in the new boards of the federations. Thus the executive committee (EC) of the NVV is fired, and the NSB-member H.J. Woudenberg replaces it as a commissioner. Woudenberg cleans the organization of the NVV, and appoints sympathizers in the most important functions. The RKWV and the CNV remain intact, although a German contact commissioner is added to their EC. The occupier wants to appease the churches.

The NVV remains politically neutral, but in fact from that moment onwards the NVV is the informal mouthpiece of the NSB, and an instrument for the execution of its policy. Woudenberg can obviously not replace all officials at the executive level, so that there he experiences some unwillingness and passive opposition. But the 800 paid NVV workers also want to continue their daily work, and carry out their duties. In august 1940 the NVV merges with the small Dutch trade association (Nederlandse vakcentrale, NVC), evidently by means of coercion. It is curious that here A. Vermeulen, who still occupies a subordinate position within the NVC, becomes the second man of the NVV, immediately beneath Woudenberg.

The German occupier and the NSB plan to unite in the medium term all Dutch workers in the Labourfront, in imitation of the situation in Germany. Therefore in july 1941 the executive board of the RKWV and the CNV are also dismissed. Woudenberg becomes the commissioner in these two federations as well. However, the executives of both federations oppose this vehemently, and inform their members that the federations will be discontinued immediately. The member Kuiper of the executive of the RKWV even says to the German commissioner: "And I must tell you, that I would rather die than work as a vassal beneath an NSB official"3. And the member De Jong of the executive of the CNV says: "We are a christian federation or we will not be"4. The members of the RKWV and the CNV follow the call of their executive, so that consequentially both federations become empty and cease to exist.

In the mean time Woudenberg merges the RKWV and the CNV (or what is left of them) with his NVV. The christian federations are forced to hand over their files and possessions to the NVV, and Vermeulen contributes in a loyal manner to this dismantling. The christian executive members have never forgiven him these actions. However, after this liquidation the employers are no longer interested in the continuation of the collective bargaining with the trade federations, because these no longer have the trust of the workers. After this rebellion the associations of employers are also discontinued. In may 1942 the NVV is truly transformed into the Labourfront. This is for most NVV officials the last straw, and they leave the organization. This is true for Vermeulen as well, and incidentally for the large majority of the members. After the war the Council of Honour of the NVV has marked this moment as the break towards collaboration with the occupier.

In the remaining war years the former chairmen of the three large federations (E. Kupers of the NVV, A.C. de Bruyn of the RKWV, and A. Stapelkamp of the CNV) now and then meet in order to have informal discussions. Although the three men have been fired, so that they are formally powerless, the official direction of the ministries remains in touch with them. For instance, in the beginning of 1942 the secretary-general of the ministry of Social Affairs asks them to co-operate in order to establish the Labourfront. After some fruitless negotiations the three former chairmen refuse to co-operate5.

The informal discussions within the circle around the director-general of Labour A.W.H. Hacke, an official at the same ministry, are more successful. Apparently the circle is formed at the start of 1943. The representatives of the employers are sometimes also present at these discussions. Notably D.U. Stikker must be mentioned, who would later become the chairman of the Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD). It may seem bizarre, but Vermeulen is also included in the circle. In spite of the resistance of de Bruijn and Stapelkamp, Kupers is tenacious of his presence, because he fears that otherwise the NVC will split off again from the NVV6. Later Vermeulen will even enter the executive board of the reconstructed NVV. Some memorial books call the circle-Hacke illegal, but considering the participation of Vermeulen and the subjects of the discussions this seems to be too much homage. The occupier may have disapproved of discussions about the situation "after the liberation", but they are not truly subversive.

The pre-war ideological disagreements seem futile under the cruel power of the occupier. Many trade union leaders (for instance S. de la Bella Jr.) have even died in the concentration camps. Perhaps it is exaggerated to call the atmosphere in the circle-Hacke friendly, but many old conflicts suddenly turn out to be easily solved. Already in 1943 Kupers, De Bruijn and Stapelkamp take the initiative to form the Raad van Vakcentralen, a kind of federation of federations. The associated unions of the three federations will form so-called industrial units at the branch levels, that is to say a branch federation. Thus the pillarization can be moderated.

Besides Stikker takes the initiative to develop the so-called Foundation of Labour (Stichting van de Arbeid), which must be a consultative body for the associations of employers and workers. Here one recognizes the public corporation, where however the state is kept out. This is incidentally the outspoken intention of Stikker. In principle the Stichting van de Arbeid is based on private law. She represents the mentality of "do-it-yourself" and of self-management in the enterprises. This offends against the view of the social-democrats.

Since this paragraph is mainly concerned with the personal relations, some remarks are desirable with regard to the situation of Kupers. After his dismissal in 1940 Kupers has no job. He finds a job as a salesman for a bee parc and sells correspondence courses for cultivating bees7. Thus he can travel a lot and have deliberations everywhere. Then Kupers establishes a capital fund, in order to support unemployed trade union officials. Halfway 1942 Kupers collects with Stikker for his fund, who in spite of the war has maintained the complete disposal of his private fortune8. Stikker donates generously, and later says: "The NVV experienced that now the big industries were immediately willing to remove the difficulties for the secret continuation of the organization". Incidentally, after the liberation the donated sum is paid back by the NVV. Long live humanity, but still it is strange.

In this paragraph first the position of the social-democrats immediately after the liberation must be explained. The preceding paragraph describes that during the war the leaders of the three trade federations come closer. A similar process occurs for the politicians, among others due to their collective imprisonment in the hostage camp in Sint Michielsgestel. Here the kept political hostages feel that their previous ideological differences where futilities, which henceforth they want to eliminate. Incidentally, this realization grew already before the war, when in 1939 the Social-democratic Labour Party (SDAP) joined the government for the first time in her history. Thus in a few years time such a mutual trust develops, that there is a general hope for a political break-through9.

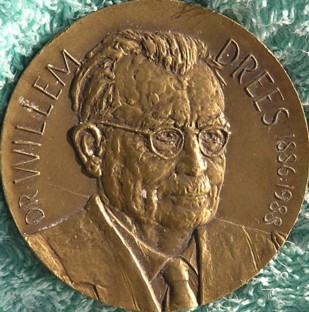

Immediately after the liberation the concerned politicians decide to subject the trust to a final test. Namely, during a year, until may 1946, the SDAP gets almost a complete control in the interim cabinet of Schermerhorn. Thus the SDAP leader W. Drees obtains the position, which immediately after the First Worldwar had been refused to P.J. Troelstra! Due to the clearly evolving political ideas of both the SDAP (and its successor the PvdA) and the KVP there is the need to postpone the national elections for a while. The mutual advances need to sink in, also in the rank and file. Formally, the cabinet Schermerhorn gets a year in order to prepare the elections. Until that moment the cabinet is supposed to merely deal with the current affairs.

In the first months after the liberation there is a political vacuum of power, and that allows for all kinds of revolutionary agitation. Undoubtedly the confessional parties hoped that these would be moderated by making the SDAP herself responsible for the political policies. This reflection is also an important incentive for Stikker to establish the Stichting van de Arbeid together with the trade union federations10. But the SDAP is eager to know what is possible, and in that year throw out a few feelers. High on the list of wishes are the public corporations (PBO), which have already been discussed in a previous column. Yet some indistinctness remains, so that it is desirable to consult additional sources of information. Fortunately, the standpoint of the social-democracy during the liberations has been documented well in the book Nederland industrialiseert, where again Herman de Liagre Böhl has written an important contribution11.

This source shows in particular, that the minister H. Vos of Trade and industries has indeed copied his bill for the BPO from his chief of cabinet J.F. de Jongh12. A special aspect of this bill is that the proposed PBO in its elaboration rather deviates from the previous SDAP-reports, such as Nieuwe organen. Thus De Jongh criticizes the presence of the representatives of the general interest in the branch councils. De Jongh comments about this aspect: "Behind this construction a view is present, which separates and tears apart the general interests and the industrial interests too drasticly". Vos and De Jongh want to compose the branch council by means of parity (bipartite), with employers and the trade union federations, and not tripartite. Thus they adapt to the ideas, that are common in the confessional circles. In order to maintain some supervision in favour of the general interest, Vos and De Jong want to appoint a state commissioner as chairman in each branch council.

Another difference with regard to the social-democratic reports is the division of the corporation into an economic chamber and a social chamber. In the economic chamber, which addresses the regulation of business economics, the employers have the democratic majority. The social chamber does have a composition based on parity, and treats all social affairs, which concern the industrial workers. A third difference with regard to the previous SDAP-NVV reports is that Vos and De Jongh principally prefer vertical product corporations as the only PBO-model. A radical aspect is that the SER does not become the federation of the corporations, but merely an advisory body. Incidentally, the SER does get a tripartite composition.

Apparently this bill is a smart solution based on compromise, which should be able to reconcile all political currents. However, in practice actually nobody likes the bill, with the exception of the SDAP (and her successor the PvdA). The employers, the liberals and the protestants complain that the corporations become too dependent on the state, due to the appointment of the state commissioner. The trade unions are disappointed, because they are represented poorly in the economical chamber, and so they can not influence the economic decisions. For, during many decades the trade union federations (notably the NVV) have cherished the illusion, that the enterprises would gradually become socialized. They can not even participate by means of the SER. Besides, they prefer a horizontal integration of the corporations instead of a vertical integration13.

The elections of 1946 result in a huge disappointment for the PvdA. Instead of the hoped break-through the party merely obtains a meagre 29% of the votes, and thus is even smaller than the KVP (32%)14. The PvdA slowly begins to understand, that the support for the high ambitions of the cabinet Schermerhorn is completely absent. She will have to adapt her ideology, and make compromises. Especially the rank-and-file can hardly accept this reality. In spite of the feelers, thrown out by the PvdA, the KVP has maintained her trust in the PvdA, so that in 1946 the cabinet Beel can be formed. However, the enthusiasm of Vos has not pleased the KVP, and now the position of the minister on Economic Affairs is granted to the catholic G.W.M. Huysmans. This minister immediately reject the PBO-bill of Vos, and installs a committee for formulating a new proposal.

The Law on the PBO of 1950 eliminates the state from the branch organizations, with the exception of the SER. The emphasis is on the "self-management" of the industrial partners. Even the input of the Stichting van de Arbeid remains present, in spite of her private nature. She is coupled to the SER, and remains responsible for the daily wage policies. In many aspects the SER and the Stichting van de Arbeid are duplicates. This must have irritated notably the state socialists, the successors of Bonger and Wibaut. It is the first political defeat of the PvdA in the cabinet. Many will follow - but large successes as well, such as the state pension. The then emphasis on the self-management becomes apparent in the Law on the works councils (ondernemingsraden, OR) as well, in 1950. The establishment of the OR is legally binding, but the law does not supply procedures to enforce them! It is worth mentioning that now the trade unions must restructure in accordance with the new branch organizations, and many do not want this. Notably the officials (brain-workers) refuse to join the labourers.

Vos is undoubtedly a victim of the break-through politics. He has some successes, such as the establishment of the Centraal Planbureau (CPB). However, Vos wants to execute the Plan van de Arbeid, his own invention, as completely as possible. He advocates the realization of a centrally planned economy in the Netherlands. In this case Vos as a person can not make the difference, that according to the beginning of this column can sometimes be achieved. Despite the chaos of the moment the social forces bring about, that the average of Quetelet perseveres. It is a hopeless attempt from the start, which shows that in the new PvdA the socialist ideology has been almost abandoned. The dogmatists miss the ability to make a pragmatic and neutral analysis. In the cabinet Beel the PvdA does not outrightly reject the centrally planned economy, but she recognizes that it is politically not feasible15.

In a previous column the social-economic ideas of order within the roman-catholic (R.C.) pillar are sketched. There, the explanation mainly concerns the organization. In this paragraph an attempt is made to also give an impression of the cultural atmosphere within the pillar. It must immediately be admitted, that your columnist does not have his own experiences. It may have become clear by now, that he is mainly concerned with the social-democratic perspective. But a deep insight is not needed for the recognition, that even the roman-catholic pillar with its long traditions is susceptible to the type of mood swings, that are described in the introduction of this column. It is worthwhile to analyze the hidden tensions with regard to the economic order. Within the roman-catholic pillar the idea of order is supported by three groups: the intellectuals, the priests and the labourers.

Among the intellectuals notably prof. J.A. Veraart has contributed much to the catholic ideas about order16. At the beginning of the twentieth century he becomes fascinated by the idea of branch councils. During the moral disorganization at the end of the First Worldwar he seizes the opportunity, and on april 19, 1919, he assembles representatives of all catholic social organizations (employers, labourers, middle-class, and farmers). Together they publish the Eastern manifesto 1919, which calls for the formation of a R.C. branch council in each branch. The councils are united in the R.C. Central Council of branches. All councils must be composed on the basis of parity, with equal numbers of representatives of the entrepreneurs and the trade union. The organization of councils will apply itself to the collective regulation within the branches.

The Eastern manifesto 1919 is impressive in its foresight. Many provisions are announced, which later will be indeed realized, such as the minimum wage, protection against dismissal, participation, and social benefits. The manifesto is welcomed with enthusiasm notably within the circles of the R.C. labour movement. Your somewhat cynical columnist suspects, that indeed the R.C. elite wants to prevent with this manifesto, that their workers become attached to the social-democratic movement. For, the contents of the manifesto closely resemble the proposals, that at the time are made by P.J. Troelstra. Here it must be taken into account, that the universal suffrage has just been established. The Central Council of branches is established immediately, and two months later during the first congress of branch councils the formation of no less than 64 branch councils can be reported.

In the years after the First Worldwar the revolutionary atmosphere rapidly wanes. Now it turns out, that the representatives of the employers are not representative of their rank-and-file. According as the rebellion collapses, the R.C. entrepreneurs gain courage again, and resist the tutelage of the council system. The R.C. press, which in the beginning writes positively about the councils, begins to wander about. The large employers leave the Central council, and in 1924 he actually ceases to exist. The general opinion is that the attempt of Veraart to organize social solidarity is premature. He has tried to coerce the social reality. The R.C. class organizations withdraw within their own class in order to reinforce their organizations. Thus it is not surprising, that in 1925 the R.C. Worker's Association (RKWV) is formed.

This brings to the fore two other groups, that favour an economic order, namely the priests and the labourers. Thanks to the special structure of the R.C. pillar these two groups are extremely integrated17. Namely, the RKWV uses a double membership: each labourer is a member of both the trade union federation and a regional diocesan association. Each of the five diocesian associations maintains the spiritual care of the R.C. believers in her region. Thus each body of the RKWV (federation, trade union, local section) gets assigned a priest as an advisor. Incidentally, this is also the case for the organizations of the other classes, so that especially the labourers as the lowest class must often be content with merely an assistant priest.

So although the R.C. church is somewhat nervous due to the emerging social-democracy, at the start of the twentieth century she is by no means an outdated institute. On the contrary, she maintains the ambition to christianize all Dutch citizens. The catholic laymen are also mobilized for this purpose, for instance in order to make house visits. Therefore in 1904 the Credo-pugno clubs are formed, which each is led by a priest. Furthermore, in 1925 the R.C. church starts the Catholic action, which is also meant to be a laymen's apostolate. Nevertheless your columnist gets the impression, that the R.C. pillar begins to show cracks under the burden of the social progress. The power of attraction wanes.

In 1931, pope Pius XI, who lives in the fascist Italy of Mussolini, publishes the encyclical letter Quadragesimo anno. The encyclical letter commands the R.C. believers to further the formation of branch organizations. Thus the Dutch catholics get a motive to cooperate with the social-democratic pillar. However, the distrust between the two pillars is still so intense, that a roman-red cabinet is not an option. Only in 1939 the SDAP joins a government, that also includes roman-catholic politicians. However, that cabinet-De Geer is mainly a war cabinet, and in may 1940 it is chased away by the invasion of the German army. All in all, since the promising campaign of Veraart in 1919 the R.C. pillar has ever avoided attempts to order the economy.

The preceding paragraphs have shown, that during the Second Worldwar the leaders of the three large pillars come closer to each other. The newly formed Katholieke Volkspartij (KVP) is willing to form a coalition with the PvdA, starting with the cabinet-Beel in 1946. Now the establishment of the public corporations becomes a part of the government program. Within the R.C. pillar the trade union federation, which henceforth is called the Catholic Worker's Movement (Katholieke Arbeiders Beweging, KAB), is the driving force behind the PBO. Its spiritual advisors in the diocesan associations are energetic advocates as well. The PBO is seen by them as the guarantee for justice, as far as the wage- and labour-conditions, and the human esteem, are concerned. A priest even states: "The corporation pursues a goal, that must necessarily be realized, similar to the goal of the state and of the family, and thus originates from God, who disposes the goal". The good intentions are clearly present18.

Nevertheless, apparently the R.C. employers do not really like the PBO, because the number of establishments after the introduction of the Law on the PBO in 1950 is scanty. Besides, in the mean time the R.C. pillar starts to collapse under the pressure of modernity. Many labourers are merely catholics in name, and join non-confessional organizations, including the social-democratic pillar. In 1954 the Dutch bishops attempt a kill-or-cure remedy in order to turn the tide, and publish a pastoral letter, which forbids the membership of the NVV, as well as the access to the VARA (radio) and the social-democratic journals, such as Het Volk. The vicar-general F. Féron of the diocese in Limburg expresses the frustration of the bishops in a striking manner: "If we would not intervene now, then in a few years the situation will get out of hand, and merely some protests or considerations in retrospect would be possible", and "Here a dam must be built with clear language, based on authority, although it is perhaps already too late"19.

The pastoral letter of the bishops has the undesired effect, that the formation of the PBO is undermined by it. For, the KAB supports the letter. Even worse is the statement of chairman M. Ruppert of the CNV, that the prohibition of the membership of the NVV for catholics is wise, and who adds that there are even stronger motives to advise against the membership of the NVV20. The NVV is furious, and leaves the Council of trade union federations. The cooperation in the industrial units is also ended. This eliminates a drive force behind the PBO, because precisely these collective associations were its strongest advocates. The PBO can function only, as long as a certain harmony exists between all representatives. Your columnist has indeed the impression, that after 1954 the Dutch movement of trade unions gives little support to the PBO.

In the preceding paragraphs it has been tried to discover the reasons behind the apparent failure of the PBO immediately after the Second Worldwar, in spite of the extant goodwill in most of the representative social-economic bodies. In the present paragraph a first attempt is made to judge the merits of the public branch corporations for the presence and the future. Loyal readers of this portal know by now, that the original social-democratic idea of the centrally planned economy became a miserable failure. She performs poorly in comparison with the free markets of private enterprises. All Leninist attemps to reform the system have turned out badly. As an excuse for the social-democrats it must be mentioned, that around 1950 this outcome was still uncertain. Nevertheless, it is striking that even in the fifties the people are already hardly willing to engage in central planning.

It is worthwhile to summarize some opinions of modern leaders about the PBO. In 1969 the chairman A.H. Kloos of the NVV writes: "It becomes clear that that the fundamental idea of corporatism - which is the origin of our PBO -, namely the creation of relations between capital and labour for cooperation and management, are a misapprehension. The PBO requires the acceptance of the existing social order, and that can and must not be proposed to the trade union movement, who has the task to change the society and to never accept the full responsibility for her. The trade union movement must not integrate in the administrative establishment"21. But also: "Nevertheless, the trade unions acknowledge the importance of a place, where at the level of the branches information can be exchanged with the employers about the economical problems". It it the time of the New Left and of the social polarization. Your columnist believes, that the trade union movement is an institute and therefore is inevitably a part of the administrative establishment. It almost seems as though Kloos wants to return to the past.

The NVV chairman and later prime minister W. Kok believes that "the [confessional] CDA [is] a party where the corporatism always occupied a central place - it is they who after the war wanted the public branch corporations"22. Does this statement express frustration about the marginal influence of the state? Following Kloos he argues: "When things truly matter, there is a certain tension between the advices about the general policy goals from the perspective of the general interest, and from the perspective of the promotion of the pure, direct, individual interests. When a choice is made for a gradual increase of the influence of the workers on the economic life, then that is inevitably accompanied by a certain acceptance of the corresponding responsibility". Furthermore, Kok concludes, that with the decentralization of the wage policies since 1982 (in accordance with the agreement of Wassenaar) the advices of the SER and of the Stichting van de Arbeid have become less important. He does not any longer see a clear reason of existence for the SER and the PBO.

Prime minister R.F.M. Lubbers believes that the SER is still useful, because: "when the pressure groups function in isolation, and do not exchange their arguments, then they become increasingly isolated and they merely want to defend their interests in a one-sided manner"23. Yet his standpoint is ambiguous: "Both the fear for corporatism, which shirks the democratic control and accountability, and the deconfessionalization and de-pillarization have contributed much in the Netherlands, but also elsewhere in Europe, to the reduction of the role of intermediate structures". He advocates a greater flexibility: "We want more freedom for the market, but we want to have better reforms than the United States by avoiding as much as possible the social abuses".

Interesting is certainly also the opinion of J.R.M. van den Brink, the minister who introduced the Law on the PBO. He writes: "The idea of the PBO develops during a period - the thirties - of social-economical disorganization, years when the industrial companions are mutually very dependent. During times of a growing prosperity few corporations are realized"24. And: "Especially in the industry there is little interest - and even resistance - among the employers and the workers. Neither does the trade union movement undertake any positive initiatives".

In a preceding column the leftwing [confessional] ARP politician and CNV trade union official Wil Albeda has been cited25: "The rather static concept of the branch, with coupled to it the idea of a branch community, fits better with the agricultural or handicraft branches than with the dynamics of a modern industry. So our ideas about the branch corporation turned out to be not really realizable, with the exception of the handicraft branch, the small industries and the agriculture, and therefore the PBO was already obsolete when this law was introduced, I fear". And: "Now I think that in the fifties we did not yet recognize the practical problems, which were created by the branch organization in the dynamics of the modern economy".

When pondering over the views of these authoritative politicians and trade union leaders, it must be concluded that they bury the public branch corporations, albeit with many flowers. To say the least of it, they have lost their enthusiasm. The grand stories of the roman-catholicism and the social-democracy turn out to be chimerical. That stimulates reflection and humbleness. How must someone feel, who once in a Credo-pugno club roamed the country in order to assure everybody that the PBO is commanded by God?26