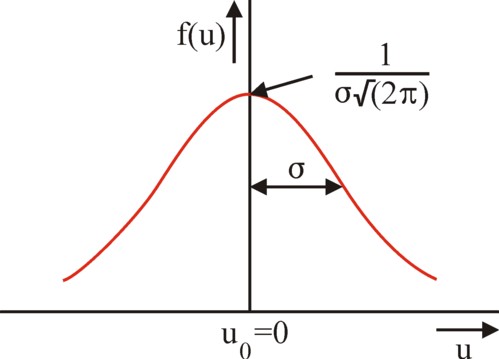

Figure 1: distribution of psychical income

Jacob van der Wijk was a pharmacist, and in his leisure time also a social democrat and marxist. However he has become nationally known for his studies about the distribution of wealth and income. His largest merit is the discovery of the logarithmic frequency distribution of incomes and wealth, incidentally at the same time (1931) as the Belgian R. Gibrat. The unique part of the theory of Van der Wijk is the connection of the distribution with the psychical income (say, utility). Thus his studies model the marginal utility of money for various income groups.

Just like Sam de Wolff also Jacob van der Wijk has published merely in the Dutch language. At least this has helped to make their ideas known in the Netherlands. Incidentally both thinkers were friends, and De Wolff makes kind remarks about his comrade in arms in his memoirs1. Both were executives of the S.V.M.V. (Socialistische Vereniging tot bevordering van Maatschappelijke Vraagstukken), at the time an authoritative sociological thinktank. Furthermore Van der Wijk was politically active among others in the Party Council of the SDAP. His main work from that episode is the book Inkomens- en vermogens-verdeling2. In 1942 he was, already very ill, deported to Sobibor in Poland by the German occupiers, where he was murdered by gassing3.

It has already been mentioned in the introduction, that Van der Wijk has developed a theory about the distribution of the incomes and wealth. The theory is built on two pillars. The first pillar is the assumption of the Belgian A. Quetelet, that an "average man" exists. That is to say, the human properties are spread around the universal average value according to a normal distribution. The second pillar is the idea of the Italian D. Bernoulli, that people are inclined to compare monetary sums not according to their absolute differences, but according to their mutual proportions.

Van der Wijk, just like De Wolff, combines an interest in sociology with skills in the use of mathematical methods. This is undoubtedly caused by the fact, that both are inspired by the books of Karl Marx4. Van der Wijk uses the method of Quetelet, which applies the formulas of the probability calculus to personal properties and behaviour. Van der Wijk justifies this approach with the statement, that the law of the large numbers is valid for many social phenomena, not just in a qualitative sense, but also in a quantitative manner. He writes: "Due to the gradual growth of groups, which are the bearers of the social life, this is also ever more the case for the purely economic phenomena" (see p.67 and further in Inkomens- en vermogens-verdeling).

Moreover Van der Wijk follows the view of Quetelet, that also subjective-psychological properties are measurable. For instance Quetelet wants to measure the property "courage" by counting the number of courageous actions of people. Nowadays his idea of measurable properties has become commonplace, among others in the personality psychology5. It is surprising that among all social sciences notably the economists have remained reserved with respect to the measurability of subjective behaviour. Van der Wijk focuses his attention on the psychical income (or wealth) due to a given sum of money.

Van der Wijk defines the psychical income u of a physical income x (that is to say, a monetary sum) as the average valuation of that income x by its owners. The psychical wealth is defined in the same manner. In fact the word "psychical" expresses here, that it concerns a utility valuation. Van der Wijk argues: "In our atomic society the factors, which determine the formation of income and wealth, have an arbitrary character. This does not imply, that there is no cause for these changes, but it means, that there are many factors present, which are unknown to us, because there is a mutual interference" (see p.67 of his book). Van der Wijk believes that the psychical income or wealth is always distributed according to a normal probability distribution.

Thus the frequency distribution of the psychical incomes u has the familiar shape of a bell, which is the hallmark of the normal curve (also called the Gauss curve). Incidentally Van der Wijk prefers to call this curve the line of Quetelet, because Quetelet has introduced her in the sociology. The "average man" has a psychical income u0, which corresponds to a certain monetary income x0. The owners of the income x0 neither feel poor nor rich. Those who have less, feel poor, in gradations which are related to the size of the deviation. Those who have more, feel rich. The law of the large numbers makes deviations less probable, according as they are more extreme. The number of poor and rich people is identical6.

In economics it is common to attach a positive utility value to property. A sum of money, however small it may be, always has a certain utility. However Van der Wijk supposes, that an income below x0 is experienced as a displeasure by its owner, because the owner feels undervalued7. Therefore he attributes a psychical utility value of zero to u0 (see p.79). The figure 1 is a graphical presentation of the distribution of the psychical incomes (or wealth). The values of the psychical incomes themselves are presented on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis presents the fraction f(u) of people, which dispose of the corresponding psychical income. In other word, the vertical axis is normalized in such a way, that the surface below the normal curve equals 1. The parameter σ measures the spread of the psychical incomes; its square is called the variance8. Together this is a frequency distribution.

Next Van der Wijk discusses the second pillar of his model, namely the size of the physical monetary income (or wealth), which is needed in order to realize the psychical income (or wealth). He introduces the hypothesis of Bernoulli, which predicts that the utility of an income increases with equal steps each time when the corresponding monetary sum is multiplied with a given constant (see p.57 in his book). In mathematical terms the hypothesis is: when the monetary income grows from x to μn×x, with μ>1, then the psychical income increases from u to u + n×Δu. Each time when the monetary income x is multiplied by μ, then the psychical income rises with the same step Δu. The hypothesis of Bernoulli takes into account, that €1000 has a different utility for a millionaire and a worker with a minimum wage.

The hypothesis of Bernoulli is satisfied, when the psychical income is a logarithmic function of the monetary income. In order to express this logarithmic relation in the shape of a formula, Van der Wijk assumes that there is an absolute minimum m of human existence. The height of this m is evidently determined by the social conditions. Nowadays m could be equated to the level of social assistance. Van der Wijk defines the height of the monetary income, which corresponds with the average psychical income u0, as m+a. He calls the parameter a the absolute measure of value.

Thus Van der Wijk finds the following relation between the monetary income x and the psychical income u:

(1) x(u) = m + a × 10u/k

In the formula 1 the quantity k is a scaling factor for the psychical income u. For u is a utility, and this does not (yet?) have a logical unit. Its absolute value is arbitrary. The formula 1 shows, that indeed the income x − m above the minimum must be multiplied with a factor 10Δu/k in order to make the psychical income rise with Δu.

Van der Wijk prefers in his book to express u in terms of x. Then the formula 1 takes the form

(2) u(x) = k × 10log((x − m) / a)

The formula 2 shows clearly, that a is the measure, which scales the income. It removes the influence of the monetary unit. Besides the formula 2 is convenient for the calculation of the marginal utility of money (income). For that marginal utility is defined as ∂u/∂x. Thus it obtains the value k / (x − m). This is precisely the hypothesis of Bernoulli, at least if it is also assumed that m=0.

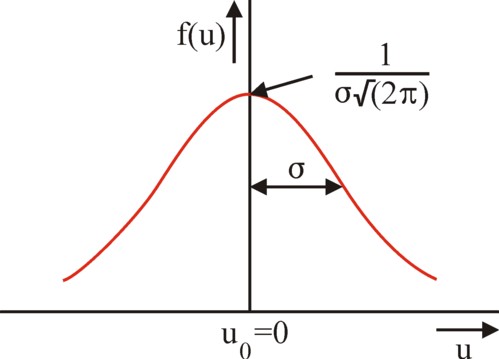

Van der Wijk has introduced the quantity m, because incomes below the existential minimum do not have a practical meaning. The quantity m is indispensable in order to model the empirical relations in a realistic manner. For the model can be tested by means of the actual income distribution, which can be obtained for instance from the data of the tax assessments. For when u(x) in the population has a normal distribution, then according to the formula 2 the incomes (x − m) / a must be distributed according to a log-normal distribution G. It is immediately apparent from the formula 1, that the frequency distribution of the monetary incomes for the richest part of the population is stretched towards the larger incomes. The figure 2 is a graphical illustration of this phenomenon.

The log-normal distribution of the monetary incomes is called the Law of Gibrat-Van der Wijk (although Van der Wijk himself mentions, that J. Wisniewski has also made the same discovery, in nearly the same period). Note that for the case of G(x) the part of the population with the average monetary income is not equal to the part of the population with the average psychical income. Furthermore x=m+a is the monetary income, which leads to u=0 (of the "average man"). Van der Wijk shows in his book, that the income distribution of many states and times can be approximated accurately by the log-normal distribution.

Thus Van der Wijk derives from the Dutch tax statistics of 1915-1916, that the distribution of the monetary incomes is characterized by m=568 guilders and a=49.84 guilders. In this case the width (square-root of the variance) σof the normal distribution equals 0.896 (see p.253). And the distribution of the Dutch monetary possessions of 1913-1914 satisfies mv = -450 guilders, av = 568 guilders, and σv = 1 (see p.258).

Incidentally Van der Wijk obtains an even better approximation of reality by assuming, that the minimum of existence depends slightly on the monetary income x. There is some logic in this assumption. For a part of the population with a certain monetary income x must estimate m in order to determine its psychical income (the satisfaction of needs). It is natural that rich people, who have a large x, will choose a larger minimum of existence m. Van der Wijk has done some computations with

(3) m(x) = m0 × (1 + ln(x / a))

In the formula 3 m0 is a constant, and ln is the function of the natural logarithm (see p.105). This formula is purely empirical, and merely chosen because of her simplicity. Van der Wijk believes, that more appropriate functions than the formula 3 may be available.

This formula concludes the essences of the model, which has been discovered by Van der Wijk. His finding to identify 10log((x − m) / a) with the utility of an income testifies to his originality. Besides his ideas have become courageous, because since then many economists have rejected the measurability of utility. The idea of Van der Wijk, that utility is measurable, is at present called the cardinal interpretation of utility. Whereas she is supported by prominent economists such as Frisch and Tinbergen, she is dismissed by others, such as Robbins, Hicks, and Samuelson9. In the remainder of this column the theory of the income distribution by Van der Wijk is related to the modern ideas about the satisfaction of needs and utility.

When Jevons, Menger and Walras related the price of products to their utility, they supposed that the pleasure itself can be measured. This is even more apparent in the work of H.H. Gossen, who was the first to stress the importance of the consumer preferences. The first law of Gossen states even explicitely that the intensity of a need falls according as it is increasingly satisfied, and that she can also become negative when the point of saturation has been passed10. In other words, the marginal utility ∂u/∂x decreases with each subsequent unit of the product. This groundbreaking idea can only be defended, as long as the consumer can indeed determine the quantitative decrease of the utility, according as he buys more of it. The valuation of the utility must be cardinal.

Cardinality exists in various gradations. Gossen applies his cardinality to the valuations by an individual for the satisfaction of his own needs. An individual can judge how much utility the possession of a product or service will yield. Van der Wijk goes a step further. For he uses interpersonal utility comparisons. The utility, which is obtained from the monetary income x1, is compared with the utility of another individual, who owns a monetary income x2. Moreover this comparison does not concern specific individuals, but the utility, which is experienced by the "average" man in a certain income category. Although this type of cardinality is rejected by many economists, it has yet an intuitive logic and appeal. Man is man. And a feeling is a feeling, a conscious state, certainly within groups11.

Later Pareto suggested, that a utility theory can be construed without the use of cardinality. In this alternative approach the quantity of the utility does not need to be measured, and it suffices to determine the qualitative order. This ordinal approach assumes, that a series of utilities u(i) can be brought in the order u(1) > u(2) > u(3) > ..., without any further knowledge about the actual differences in utility. Then the first law of Gossen must be abandoned12.

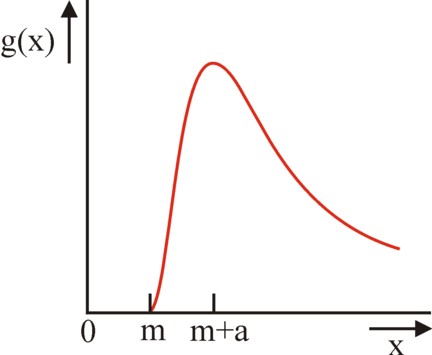

However, the first law of Gossen is so important for the economic theory, that its abolition must be followed by some kind of replacement. The ordinal approach makes special demands on the so-called indifference curves in order to fill the void. Indifference curves indicate which combinations of quantities (x1, x2) of two products lead to identical experiences of utility. Therefore they are also called iso-utility curves. The figure 3 illustrates this concept in a graphical manner. Now in the ordinal approach the demand is made, that the indifference curves have a convex shape. That is to say, the bulging side of the curve is directed towards the two axes13.

Although this modern approach, which is based on the mathematical theory of sets, is formally right, the demand of convex behaviour is not self-evident. The hypothesis misses the intuitive logic, which is attached to the first law of Gossen. And that is unpleasant.

The normal distribution of the figure 1 illustrates how the utility of the incomes is distributed across the population. The distribution can be made discrete, so that it is written as f(u1, ..., un), where the population is divided in n income groups. Then (u1, ..., un) can be interpreted as a vector u with n components in the space Ωn of socially allowed utility combinations. Van der Wijk does not state, whether the real distribution is just. That is the field of work of the so-called welfare theory. She is mainly concerned with the study of the collective welfare, and its optimization. That is to say, actions are sought which make the utility vector (u1, ..., un) maximal. Here n counts all individuals, and not certain groups. Besides, the concept of welfare is not simply coupled to income, like Van der Wijk has done in the formula 1. Instead the calculation uses a welfare function W(u)14.

It is interesting and instructive to mention several approaches, which are current for the social welfare function15. In the utilitarian approach the function W(u) = Σi=1n αi × ui must be maximized. Here the αi are weighing factors, which may also equal 1. In this option the cardinality is interpersonal. Note that here the social welfare will even increase, when the poor must give in, at least provided that the rich will be over-compensated for this loss.

This injustice can be eliminated by the demand of an egalitarian distribution, where one has ui = β (constant) for all i. Then the total welfare is W(u) = n×β, and this can not be improved by a redistribution of the incomes or goods. Nowever the most popular demand for the distribution (rightly or wrongly) is the maximin principle, which is based on an argument by the sociologist J. Rawls. The maximin principe requires, that the smallest occurring value of utility ui is maximized. In mathematical terms: maximize W(u) = mini ui. This means for the distribution according to Van der Wijk, in the figure 1, that the left-hand tail of the normal curve must be "cut" as high as possible. In principle it is conceivable, that this may require an excessive increase in the wealth of the rich.

The utilitarian and maximin principles do not a priori make further demands on the welfare distribution. They are rules of thumb in order to steer the society in the desired direction.

In this paragraph a succinct description will be given of the welfare functions in the income theory of the Dutch economist Bernard van Praag16. The interesting aspect of this economist, and incidentally also of his Leyden School, is that they have rehabilitated the cardinal utility functions. However in his approach the cardinality remains individual, and thus does not become interpersonal. It is remarkable, that Van Praag finds a log-normal distribution function for the individual utility of income. Of course here the context differs from the theory of Van der Wijk, which describes the social distribution function. But it does show, that Van der Wijk does not argue in an intellectual vacuum.

In fact Van Praag supposes, just like Van der Wijk, that the individual finds it difficult to oversee situations with very large quantities. In order to evade this problem the valuation transforms the differences between physical quantities of products into ratios, and not into absolute differences. Thus the (individual) utility function can remain simple, although the physical density function has exponential extremes.

This concept can be generalized for a monetary sum, or in the words of Van Praag for the "representative (or homogeneous) good". The utility distributions of all the independent products in the basket of goods of the individual can be aggregated in the distribution of this representative good, which thus itself obtains a log-normal shape. In this way the preference curve of the individual is construed in the monetary domain.

It is clear that the probability distributions of Van der Wijk and Van Praag have a different meaning. In the case of Van der Wijk the utility function describes the social spreading of the satisfaction of needs, due to the influence of various biological and social factors. In the case of Van Praag the utility function describes the needs of the individual, irrespective of their eventual satisfaction. He chooses to vary the utility of each good between 0 and 1, so that there are neither negative utilities, nor infinite utilities, such as is the case in the theory of Van der Wijk. A utility of 1 implies that saturation is reached.

A fascinating aspect of the research of Van Praag and the Leyden School is their application of the theory in empirical studies. Here measuring methods are used, which are already common in sociology and psychology. Also for this reason your columnist has felt obliged to include the present paragraph. If possible future columns will return to the findings of the Leyden School, and to their relation with the theory of Van der Wijk.

Finally it is desirable to comment on the present opinion with regard to the theory of Gibrat-Van der Wijk. This can be brief, because she is still among the best that is available. There is criticism, but this is mainly due to the unwillingness to accept probability processes in the formation of incomes17. In the same way the objection is sometimes made, thay the various causes of inequality are mutually dependent. For instance a socially weak posititon will probably correlate with a poor education18. That undermines the assumption of coincidence, which forms the basis of the model of Van der Wijk. Van der Wijk himself acknowledges this objection, and answers on p.76 of his book: "This now (the independency) does not a priori need to be the case. Logic can merely have us assume a priori, whether the fulfilment of these conditions is possible or even probable, the test, in casu the statistical verification must decide whether that assumption was justified"19. And in this perspective it can not be denied, that indeed the theory of Gibrat-Van der Wijk has produced good results.