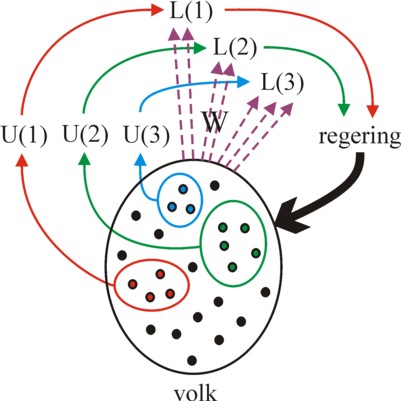

Figure 1: Communication flows in

pluralism

U(k) = target function; L(k) = leader k;

W = choice function of voters

In this column the present-day christian-democracy is studied. As a reminder the political philosophy of the state is summarized again. It is compared with the evolutionary institutionalism, which is now also applied in economics. Then the hallmarks of christian politics until the formation of the CDA are sketched. Against this background the ideas of five christian writers are discussed, namely H.M. de Lange, C. Huijsen, A. Rouvoet, J.P. Balkenende, and S. Buma. An evaluation concludes the column.

Soon after the foundation of the Heterodox Gazette, discussions about the political democracy obtained a prominent place. For, the economic markets are embedded in the social system, and therefore they depend for their functioning on the political system. The citizens will aim to arrange their society in such a manner, that the general well-being W is maximal. Unfortunately this optimum can not be realized in a natural way. In 1651 the philosopher Thomas Hobbes concluded, that in the natural state there is a war of all against all. The state and its monopoly of violence are indispensable for maintaining the order. In other words, the state dictates its own order to society1. It can be summarized in a target function U. Therefore the state executes the transformation W → U.

In the democratic state the conflicts of interest are restricted by the Constitution. The parliament decides about legislation, based on majorities. Since more than a century, parliament is divided in coherent groups, which are supported by political parties in their programmatic activities. These parties can be viewed as circles k of citizens, which unite around shared morals U(k). According to the group theory such circles are most effective, when they delegate their power to a leader L(k). During the periodical elections the leaders compete for the approval of the electorat. The outcome of the elections defines the framework, which guides the leaders in their attempts to form a temporary coalition which together will support the government. The government determines the political policies during the time, when it is in power. This democratical process can be modelled as a control circle with feedback. See the figure 1.

Apparently there is a continuous tension between the participation of the citizens and the delegation of power to their leaders. The liberal fundamental rights guarantee a number of liberties to the citizens. Besides, there are social fundamental rights, which introduce a certain social equality, so that all citizens can indeed use their freedom. In this model the parliament is the link between participation and delegation. It depends for the supply of its information on the signals from society. This raises several akward questions. For instance, which democratic form must be given to the weighing of group interests? And which policy is developed for furthering the personal autonomy? In other words, are the citizens made sufficiently capable to express their will? To what extent does the state try to control its citizens by means of social formation?

The combination of participation and delegation implies, that there does not exist a fixed central Will. The historical development of society follows a certain path. This is especially clear in political systems, which order and regulate society by means of a democratic feedback. Therefore the Gazette has recently paid attention to the evolutionary institutionalism. This assumes a psychological model, where each circle adopts a mental model. Together the circles form a cognitive structure. Informal institutions guarantee, that the social behaviour is somewhat predictable. They lower the transaction costs, which must be paid by citizens in their mutual exchange. The figure 1 shows, that the informal institutions are tested in a cyclical process, and are therefore subjected to a permanent process of learning. There is innovation, which is spread by imitation.

Nevertheless, the informal institutions do not suffice, notably in the modern mass societies. There are so many different circles, that the society is pluralistic. Due to the decreasing cohesion the attractiveness of opportunist behaviour rises. Therefore the modern society needs all kinds of formal institutions. Together they form the central state of Hobbes. These are often simply the recording of informal institutions, because these have proved to dispose of an appreciable social support. Thanks to the laws of the state each circle can enforce the obedience to contracts. The path-dependent institutions are the result of a struggle for power, aimed at furthering partial interests. However, in a democracy one may hope, that they nevertheless improve the social effectiveness. Then the function U is sound.

Like Hobbes already concluded, the process of making political decisions by no means is harmonious. The psychology proves, that the circles have many biases and stereotypes about each other. They are inevitable, because the capacity of the human brain to process information is limited. Unfortunately, in unfavourable conditions they can stimulate hostile behaviour. Nonetheless, at least in the west a political system develops, modernism, which is fairly successful in curbing hostility. The sociology characterizes modernism by individualization, differentiation, flexibilization, rationalization, and domestication2. These are tendencies, which reduce the need for coercion and violence. Nevertheless, also modernism has sometimes established wrong formal institutions.

A striking postwar example is the attempt of the Dutch state to impose the public branch corporations (in short PBO) to society. Although there was from the start much resistance against this formal institution, the state only gave up this ambition after several decades! The failure of the PBO has certainly contributed to the social confusion, which was so omnipresent in the Netherlands after the early sixties. The PBO idea was a shared mental model of the then roman-catholics and social-democrats. It was mainly designed at the central level, so a top-down innovation, although the collective agreement (CAO) was a (modest) predecessor, which emerged fairly naturally from the economic practice. It turns out that the PBO unnecessarily limits the individualization, differentiation and flexibilization. Apparently the circles can indeed sometimes cherish an unsound mental model

When the administrative system is subdivided in the state, the market, and the social circles, then three ideologies can be derived: conservatism, liberalism and the social-democracy3. For years, the Gazette studies the mental model of the social-democracy. It propagates in essence three institutions, namely the socialization of property, the economic planning, and the collective control of investments. During the twentieth century the experiences have shown, that these three institutions are unsound, at least in the rigorous form, which the social-democracy promotes.

It is bad, that the social-democracy incites the citizens towards hostility against the leaders of the industries. Originally, this unrealistic stereotype had the form of the class struggle. The citizens must eliminate the existing order during a revolutionary process. This historical breach of course contradicts the insights of the evolutionary institutionalism4. Although the paradigm of the class struggle is untenable, the social-democracy could never truly shake it off. During the seventies Nieuw Links revived it, under the name of polarization. During the nineties there was a return to realism. But in the course of the new millenium the social-democracy again became radicalized5. Therefore your columnist has now shifted his attention.

Since more than a year the Gazette also studies the christian-democracy, which is an important representative of conservatism. Other than the social-democracy, the christian-democracy does trust the ruling informal and formal institutions. It is the hallmark of the christian-democracy, that she traditionally accepts the church as the leader of morals (say, the shared mental model). God's Will determines the form of the target function. In other words, God is the sovereign, and not the people. Finally, the christian elite reconciles with the democracy, but she wants to maintain a certain aristocracy. The competition for the truth with respect to God's Will remains in the hands of the churches. In roman-catholicism the Pope is even the wordly representative of Jesus. The conservatism emerges from the view, that God's Will becomes visible in history.

This view of life implies, that the christian-democracy is more interested in morals (the value-rationality) than in effectiveness (instrumental rationality). Materialism is distrusted. It is convinced, that finally the whole population will be converted to the christian truth (christianization). The roman-catholics and the Calvinists have translated this ambition in the establishment of a cohesive personal circle, a so-called pillar, in order to organize their mission in a powerful manner. However, a previous column has shown, that in the course of the twentieth century christianity loses its supporters. The mission had no chance, and then the pillar became an inner directed circle. The ties with the external world were weak. Therefore the pillars were bad in innovation. The feedback is stifled.

The decline of christianity shows, that its morals are insufficiently appealing. The christian anthropolgy (insight in human nature) misses accuracy6. Namely, it rejects individualism and rationalization. Although the christian-democracy has a better mental model than the social-democracy, yet its rejection of modernism was a dead end. The maintenance of the pastoral leadership of the church is irreconcilable with individualism. The neglect of the instrumental rationality weakens the social performance. The pillarization is in conflict with differentiation. In retrospect the complacency, with which the pillars embraced isolation, is astonishing. The pillars have probably been artificially maintained for too long. Then internally a huge pressure to change builds up. This era illustrates again, that institutions can degenerate into obstacles.

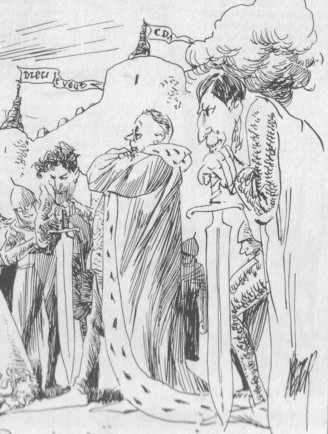

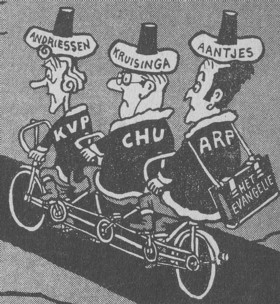

Only in the late fifties do the pillars reluctantly acknowledge their failure, so that they become more open for other ideas. Partly, the churches themselves are the driving force in the shifting of their institutional path. In this way, during the sixties the roman-catholics (in short RC) and protestants (PC) can quickly reconcile. Their elite introduces a new theology, which attaches more importance to the social action than to the profession of faith. The churches become wordly. This new message is actively propagated by the christian media7. In 1966 the protestants and the Calvinists start the "Together on our way" deliberations. This undermines the diversity in confessional politics. Next politics perforce begins to reduce the gospel to a source of inspiration, without engagement. Incidentally, the confusion among the religous elite again leads to the alienation of her traditional rank-and-file.

In the Netherlands the adaptation of the christian-democratic model approximately coincides with the foundation of the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (in short CDA), in 19778. The idea of the Devine sovereignty is abandoned. During the preparations of the CDA the answer-philosopy is developed. It requires, that the CDA gives an "answer" to the Gospel9. Those who want to become active in the CDA, must accept the Gospel as line of action, but do not need to adhere to it. Thus God is no longer the undisputed sovereign. The core principles of the young CDA are the shared responsibility, justice, solidarity and stewardship. Here the past of the christian-democracy can be recognized: conservatism, paternalism, moralism, personalism and a moderate internationalism. Within the oecumenical movement especially the RC Church traditionally has the ambition to be a global religion, more than the PC Church.

In the beginning the ideological innovation is successful, because the establishment of the CDA indeed slows down the decline of confessional politics. However, the innovation is now a continuous process, which finally does not end the losses10. Therefore it is worth studying the accommodation of the requirements of modern times in the renewed principles. Now a fascinating question is how the modern christian political scientists and authors view the democratic ideas, and notably how they want to morally define the general interest. Your columnist limits his analysis to the political thinkers of the protestant religion, because he is most familiar with it. Besides, that restriction makes the quantity of relevant publications less immense. Five political authors are presented, namely H.M. de Lange, C. Huijsen, A. Rouvoet, J.P. Balkenende, and S. Buma11.

In the mentioned list of authors, De Lange and Huijsen illustrate, that believers can be found in the whole political spectrum. Namely, De Lange is a socialist and Huijsen is a social liberal. They are discussed here in order to clarify the flexibility in confessional thought. The ideas of De Lange are taken from his book De gestalte van een verantwoordelijke maatschappij (in short GVM)12. Although De Lage himself is a protestant, his book analyzes the views of the global oecumenical movement, as it is expressed by the World Council of Churches. Since the twenties of the twentieth century this Council (and its predecessors) publishes a report each decade, wherein an evaluation is given of the social order. Incidentally, since the sixties the Council concentrates its activities more on the Third World than on the west.

Of old the churches believe, that the society is ordered as a result of a natural development, under the supervision of God. Therefore the religion does not interfere with collectives, which implies that religion is purely personal. The liberalism of the nineteenth century reinforces this attitude. However, in the course of the century the socialist movement argues with an increasing force, that alternative orders are conceivable. Therefore the churches lose supporters, especially among the industrial proletariat, and they try to combat this by proposing their own ideas with regard to a christian order. Thus the theologists begin energetically to study worldly affairs, such as the concrete order of the economy13. The World Council of Churches even forms many commissions, where theologists and scientists together develop the theory of the christian order (see p.25 in GVM). De Lange is one of these scientists.

System builders must dispose of their own anthropology (GVM p.242). Christians find their anthropology in the Bible, which is the revelation of God. God has made his son Jesus the example of mankind (p.57). Therefore the christian anthropology is based mainly on Jesus and his love of his neighbours (58). Unfortunately the love of self has the result, that man again and again succumbs to sin (p.63 and further, 245). The pastoral direction to faith is necessary in order to combat the human imperfection. Sin results in a social system, which itself has become unsound (88). The World Council of Churches complains, that the present society creates too many obstacles for the experience of faith (that is to say, for the individual unfolding within the personal group) (GVM p.28, p.66 and further, p.90). Individuals become confused, and lose their meaning of life (236, 241).

The Council notably rejects in all of its reports the prevailing materialism, which degenerates into commerce and the desire for profit. The reports see the solition in the mutual or social responsibility (GVM p.41, 235, 241). This is pre-eminently a christian norm, and a hallmark of God's Kingdom. The people must form and educate each other. Here the state has its own responsibility, and must develop a policy of culture (238). Such a policy equips the people with social responsibility (92). See the core questions at the beginning of this column. That is to say, the churches and their members must actively press politics to realize a christian order. This is indeed a striking anthropology: the population as a majority has an unsound attitude, and she must be reborn by the intervention of the church!

De Lange even argues, that the churches and their members must identify the errors in the economic system (92)! He does not shrink from political propaganda, and wants to realize the responsibility with socialist principles. He naturally believes, that the christians must promote the social security (49, 120). He is an energetic advocate of the mixed economy (78). With a reference to the American economist J.K. Galbraith he wants to spend more money on the public sector (p.104 and further)14. Furthermore, he wants to further reduce the inequality of the income distribution (109). And he maintains that the state must create employment (125). Thus De Lange indeed defines the christian variant of the transformation W→U, on the understanding that he equates it with social-democratic policies!

The politician Coos Huijsen was mainly important as a party ideologist. His career is striking. During the seventies he is active in the youth movement of the CHU, and next enters parliament for that party. However, then he switches to the PvdA, where he is mainly active as a publicist. For the present paragraph his book De PvdA en het Von Münchhausen syndroom (in short VMS)15 is consulted. Huijsen tries to be the successor of the christian PvdA ideologist W. Banning. Just like at the time the CHU, Huijsen is not interested in political programs (p.17, 134 in VMS). The PvdA must derive her profile from a persuasion, and from morals (p.47, 138). According to Huijsen the essential values are: justice, freedom, responsibility, solidarity and respect (p.49, 61, 76). Personal initiative and assertiveness are indispensable (33, 58).

The core of Huijsen's philosophy is his dislike of the so-called mass man. The society becomes larger and larger, because this leads to gains in economic efficiency. Huijsen calls this the idea of utility (utilitarianism). However, in this way the individuals become anonymous (36). Huijsen believes, that they can not process the complexity and information (38). That alienates them, because man can only develop personal morals in small circles16. The idea of utility leads to consumerism and commerce (14, 37), where the mass media dictate the individual consumption (69). Thus Huijsen is ambivalent with regard to progress (16). He believes, that small-scale formation of groups is more important than advantages of scale (109). Now Huijsen even becomes sceptical towards growth, and wants to slow down consumption (62, 64). In this respect he as a predecessor of the female politician Femke Halsema17.

It is curious that Huijsen prefers a political system with two large blocks, namely progressives and conservatives. Apparently here the large scale is not a problem. Just like Banning, he embraces the postwar Breakthrough. The progressives want to make society more humane by stimulating personalism. The meaning must come mainly from religion, arts and the sciences (30,70). Here Huijsen recommends to limit the state interventions (42, 59), because they do not fit with assertiveness and mutual resposibility. The state is merely a stimulus and regulator (86). In that sense the philosophy agrees well with the former CHU, the radical centre, or social liberalism.

According to your columnist the view of Huijsen is problematic. He formulates a system of values, but does not support it with a credible anthropology. This gives his image of man the appearance of an imposed dictate, which evidently conflicts with the also recommended assertiveness. Notably, the citizen must give up his freedom as a consumer, in exchange for a culture policy. The criticism of the idea of utility has lost cogency, since nowadays this idea is popular in psychology and sociology. See the rational choice paradigm. Besides, nowadays there are good alternatives for the speculative morals of Huijsen. For instance, the social psychology tests models of behaviour with experiments, and thus offers a proven image of man18.

The politician André Rouvoet was the party leader of the Calvinist Christen-Unie (in short CU), which was established in 2000 by the merger of the tiny parties GPV and RPF. His view is interesting, because the CU is less wordly than the CDA. Your columnist consults the book Het hart van de zaak (in short Hz)19, which clearly expresses the ambivalence of the christian-democracy with regard to the modern state. The CU wants to serve the Kingdom of God. This includes the universal ethics of truth, an ethical pluralism, tolerance, the natural rights, and the protection of life (Hz p.46 and further). The truth in the Bible is absolute, and has an above-individual objectivity (p.72 and further). There is freedom in responsibility. Justice and stewardship are more important than effectiveness (183). Charity and the love of one's neighbour go deeper than solidarity, because they include servitude and sacrifice (102)20.

Now Rouvoet analyzes the transformation W→U. He rejects the ideas of the Enlightenment, which make the truth relative, and which open the door to the dictature of the majority (p.46 and further, 206). The present-day citizens are not very assertive, because they react impulsively (p.125 and further). Therefore Rouvoet rejects the direct democracy (114), and prefers a strong moral leadership, which builds trust and unites (125, 143)21. Politicians must testify. Such leaders point the way, and have authority. When a new category of leaders appears, then the social responsibility can be given back to the church, the enterprise and the family (20-21, 180). The formation occurs within the family, the school and the church (97). The state must step back. The citizens must pay for their consumption of services, so that the taxes can be reduced (23). Here and there in the book Rouvoet complains about the addiction to subsidies22.

At first sight this plea agrees with the social-democratic movement of the radical centre, which attaches value to the together-efficiency. However, whereas the radical centre expects an increased effectiveness from private initiative, as well as personal emancipation, Rouvoet hopes that it will stimulate the discussion about morals. He wants to prevent, just like de Lange, that individuals stray spiritually in anonymity. But his remedy bears a resemblance to the Calvinist dogma of Abraham Kuijper, and it may be argued, that this is by now truly made obsolete as a result of better insights.

The present paragraph is based on the book Anders en beter (in short Ab) by J.P. Balkenende23. After the neutral left-liberal cabinets Purple I and II, Balkenende advocates a return of morals in the state policies (Ab p.16, 52, 116, 120). Morals are indispensable for the maintenance of the constitutional state and its constitution (Ab p.60, 121). Balkenende propagates the CDA morals, and tries to translate these in a political policy. He stresses, that the individual freedom (autonomy) must go with responsibility (duties). The love of one's neighbour and solidarity in communities have their own value (p.69, 118). Therefore he believes, that the policy of the state must aim at households, and not at individual independence (26, 70).

Furthermore, Balkenende refers to the principle of spread responsibility. He wants to make the civil society (community, "social mid-field") more important, at the cost of the market and the state. This proposal implies that the social order must change (104). The aim is to stimulate the personal responsibility and the private initiative (27, 106). This is the now well-known sovereignty in the personal circle (57), but Balkenende prefers the term "social entrepreneurship". It must be accompanied by regulations, so that the financing by the state can be diminished. The costs of social enterprises must be paid by their clients, for instance by means of appropriate contributions (90, 96, 107). Such enterprises can be active in the traditional policy domains, such as insurances, housing, care, broadcasting, and education (27, 57).

Proposals such as collective morals and social entrepreneurship remind of communitarianism. Balkenende himself acknowledges this (Ab p.25). The secular morals of the CDA indeed remind of the I & We model of the communitarianist A. Etzioni. In Anders en beter no connection is made with christianity24. Elsewhere he does attempt this, and makes ambivalent statements. In 2000 Balkenende states, that the consumerism and materialism are not well reconcilable with serving God. He embraces the Rhineland model, which is built on christian-social principles. He rejects the Anglo-saxon model, which aims at making profits. The churches remain necessary as a valuable source of collective morals25. Nonetheless, Balkenende does value competitive entrepreneurship. For instance, he describes innovation as the mentality to strive for excellence and gains26.

At the moment, the politician Sybrand Buma is the CDA leader, and therefore his view is also interesting. Your columnist consults his book Tegen het cynisme27 (in short Thc). Buma does not share the strongly evangelically inspired conviction of previous generations. He sees the belief simply as the conscience of a higher reality (Thc p.113). The love of one's neighbour is a life style of unselfishness (p.101). Buma states, that nowadays the individual rights begin to dominate the duties (p.74, 157, 196). The welfare state furthers egocentrism, undermines the responsibility, and stifles the personal initiative (p.146-147)28. This abuse is partly caused by the New Left, which has propagated the relativity of culture (203, 211). Therefore Buma wants to promote bonding morals, which bring back trust in society. Citizens must feel mutually responsible.

Therefore it is necessary to give more room to the social circles, at the cost of the individual or the state (78, 145). The family is essential, because the core values are transfered by formation in the personal circle (73). For the same reason, family enterprises often feel socially responsible (81)29. The churches also remain indispensable (71). The CDA translates this into the spread responsibility. Just like Rouvoet, Buma does not demand effectiveness of the social circles. On the contrary, the state has rattled on in this respect (216). Buma wants to further the tradition and morals at the cost of individualism and competition (223). Autonomy is not possible without harmony. The reader may observe, that the CDA ideology has not really changed since Balkenende.

The christian-democracy does not have a sound anthropology (image of man), but nevertheless it has the pretence to solely know the truth. The hallmark is the reference to the love of one's neighbour, which is rather a simplification of human nature. Sin is combatted by means of super-natural commandments (value-rationality), which go beyond merely the human rights. The individualization is distrusted, as far as it leads to the idea of utility and hedonism (instrumental rationality). This would be sinful. Since the christian morals must be imposed on the people as a dictate, the christian-democracy is inclined to be paternalistic. It wants pastoral leaders. This is true even now, although by now the Kingdom and Will of God are abandoned as leading goals. In this secular form the christian-democracy represents communitarianism.

The christian-democracy pleads in favour of autonomous social circles, since there the love of one's neighbour must be realized. That is to say, it promotes the maintenance of institutions, especially those that lead to reciprocity and duties. Such institutions have a value in itself, and therefore do not need to be effective. Effectiveness is not a leading value. In fact, materialism and competition represent the undesirable idea of utility. Apparently confessionalism is not particularly alert with regard to social stagnation, as incidentally became already clear during the European Middle Ages. The autonomous circles are commonly established by the social elite, which in this way can expand her power. So although the christian-democracy presents a more sound view than the social-democracy (which has become stuck in class thinking), it still gives feelings of discomfort.