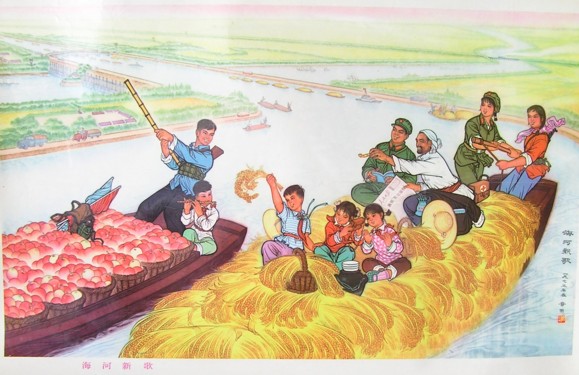

Figure 1: Chinese poster

Since more than a century the capitalist west tries to combat the poverty in the Third World. The present column discusses several economic theories, which make suggestions for an effective development policy. First, the dualism of J.H. Boeke is described. Next, the proposals of the planning committee of the United Nations, chaired by Jan Tinbergen, are studied. This is concluded with a retrospection in 1992, mainly by H.W. Singer. As a complement, the views of the then Novib director M. van den Berg are summarized. And an impression is given of the operational methods of private aid organizations.

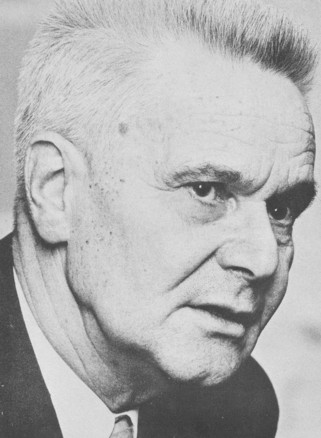

Economic growth is an indispensable condition for guaranteeing the human welfare, and in particular the individual development. Therefore the theme of growth is central in most columns of the Heterodox Gazette, as well incidentally as in the work of its namegiver Sam de Wolff. Notably a study has been made of state interventions, that could contribute to a rapid growth. The Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen pleads in favour of economic planning as a means to further a targeted and effective state policy. In the planning approach the targets of the state are formulated with precision, and policy instruments are selected, that are most suited for the realization of those goals. Tinbergen even has developed a mathematical model for the calculation of the relation between the policy goals and instruments.

Tinbergen has presented his ideas during the fifties of the last century. Since then much practical experience has been made with the planned control of the national economy. The most rigorous variety can be found in the Leninist planned economies, which preferred a strictly centralized system, with merely state enterprises. The Leninist system has failed, because the whip of the market operation can not be missed. Incidentally, Tinbergen himself has rejected the Leninist dogma, and advocated the preservation of a significant private sector. Such a mixed system of private and collective activities has for instance been realized in France, during the period between 1950 and 1975. At the time the French planning system could match the economies in its neighbouring states, which did not use planning, and relied on the operation of markets.

Nevertheless, the French planning became increasingly troublesome, according as the economy integrated into others within the frame of the European Economic Community. The French planning system received its death-blow during the seventies, when the two oil crises (1973, 1979) caused violent fluctuations of the global conjuncture. According as the state continues to merge its economy with foreign economies, the national planning becomes increasingly powerless against the unpredictable developments elsewhere in the world. Since the eighties planning is hardly applied any more in the western industrial states. It has given way in favour of computations of economic scenario's, where the outcomes are the basis for policy choices. Here the state has retreated somewhat from the economic activities, and relies more on the productive forces of the private markets.

Even though the globalization and her consequences do not make the theory of Tinbergen and his adherents obsolete, they do diminish her significance. In a modern economy the input data are simply too capricious in time. Nevertheless, it could be a argued, that the planned system is still attractive for primitive and backward states, such as can be found in the Third World. For, their economy consists mainly of agriculture, which produces mostly for the needs of the domestic population. The integration with the global economy is still weak. Thus they are more or less in the French situation immediately after the Second Worldwar, when good results were still obtained with state planning. The present column describes the insights with regard to the economy in the Third World, and analyzes the proposals, that have been made for furthering its growth by means of state interventions.

This paragraph is mainly based on the book Oosterse economie by the Dutch economist J.H. Boeke1. In this book Boeke analyzes the economy in the Third World, albeit that he restricts his studies to East Asia. Incidentally, this restriction does not affect the validity of his observations and conclusions. Boeke states, that the Third World is characterized by a dual economy. At the time approximately 80% of the working population lives in the countryside, and performs agricultural activities under feudal conditions there. He calls this system a pre-capitalist economy. The central element for the activities is the village. The villages are arranged for self-provision, and for mutual aid. However, in the cities the modern capitalism emerges. The people convert to individualism, so that the relations change into those of an exchange economy. The goal of making profits is introduced into the productive activities.

The cities are attractive for the social elite, because they offer various facilities, such as trade, education, care, and security. Therefore the rich citizens move to the cities, which thus become the centres of political power. A social and spatial division between the prosperous citizens and the large masses of backward peasants is formed. However, these two economic systems can not exist in isolation, and yet have to interact. For, the state supplies various services, such as legislation and regulation, education and care. Moreover, in the villages a consumptive demand for some industrial products emerges. In other words, the villages start to import goods and services from the cities. These can only be paid, when the farmers start to "export" a part of their production to the cities.

Now Booke states, that often the domestic agricultural production is less suited as an export product. Therefore the farmers must change partly to products, that do not fulfil their own needs. This withdraws agricultural land, that used to be employed for their own food provision. Besides, the labour productivity of the farmers is miserable, so that their products have relatively little exchange value. The low productivity is a hallmark of the feudal culture, which attaches little value to effectiveness and efficiency. The production in the countryside is practically deprived of innovation. It is true that cattle is often used for transport and for earthwork, but this practice is mainly intended to symbolize status. The stock-farming is totally unprofitable. The consequence of this careless way of life is, that the countryside continues to make debts in the cities.

On p.97 Boeke even states, that the farmers are "mad on credits". They simply are not capable to use money effectively. Also in other respects the farmers have difficulty in adapting to the facilities of the modern society. For instance, thanks to the improved care and infrastructure the death-rate decreases, so that an overpopulation occurs. The people continue to create large families - although the farmers sometimes resort to infanticide2. The education and the capitalist trade undermine the traditional way of life, and they make the farmers aware of the misery of their existence. This is actually desirable, because dissatisfaction can perhaps awaken the farmers from their mental apathy. However, Boeke takes a different view. He is convinced, that the urban industry can not grow fast enough to supply work for the excess of labour in the countryside. Besides, he doubts that the farmers can adapt mentally to the modern way of life.

Boeke even denies, that the productivity in the agriculture can rise (p.106). There is simply a lack of spirit of enterprise (p.72). The Asian farmer is not a homo economicus. The Green Revolution is still beyond the imagination of Boeke. Thus finally in chapter 11 (De armoede en haar leniging) Boeke makes the policy recommendation to restore the villages. The export from the cities to the countryside must be reduced. The state must even strengthen the culture and the religion of the traditional village, so that the farmer's family will reconcile with its miserable fate. Here he cites an expression of Mahatma Ghandi: "Plain living and high thinking". Your columnist acknowledges, that he has to swallow at this unexpected conclusion. It is clear that Boeke is dimmed by the poverty in the countryside, and by the attempts of the western administration to eliminate the abused.

Nevertheless, an official ought to appreciate more the possibilities of regulation, of advice and of other state interventions. On several places (p.31, p.44, p.98) Boeke does acknowledge, that the colonial rule in the Dutch Indies succeeds in somewhat protecting the farmers economically, even more than for instance the regime in China. Moreover, the sketched situation reminds of the English development during the eighteenth century. For instance, this type of advancing capitalism has been described long before by the political thinker Karl Marx, in chapter 24 of the first volume of Capital, about the original accumulation3. It can be expected, that also in East Asia an effective economy will develop. But apparently Boeke has become desillusioned.

In principle the preceding arguments about Asia also hold for the Third World in the other continents. However, Africa south of the Sahara (also called sub-Sahara) deserves a separate discussion, because there the historic conditions for development are particularly unfavourable. This is explained clearly by D. Acemoglu and J. Robinson in their book Why nations fail4. In most states of sub-Sahara Africa a central authority, which maintains order, is absent. On p.92 and further Congo is discussed as a typical example of the reigning abuses. European travellers report already in the fifteenth and sixteenth century that the state is miserably poor. Then the empire is called Kongo, and it is ruled by the governors of a king. Slavery plays a central role in the economy. The elite of Kongo uses slaves for her own estates, and also sells them to passing Europeans.

All trade is a monopoly of the king. And he plunders the free farmers by means of high taxes. Therefore the farmers have no incitation to invest in their own enterprise. Even when they get to know new agricultural techniqes, they refuse to apply them. Here the administration is the main threat for the properties and human rights of her subjects. Nevertheless, the elite around the king is extremely wealthy. During the seventeenth century the king has a standing army of 5000 warriors, which at the time is an enormous armed force. It can generally be stated, that slavery is a domestic hallmark of the states in sub-Sahara Africa. Incidentally, the Portuguese have worsened the situation in Kongo, because they buy slaves, and in exchange supply weapons to the Kongolese king (p.112). Thus he is better able to acquire new slaves, and to suppress rebellion.

As far as on this continent powerful states are formed, they engage in warfare and plundering, with the goal of acquiring yet more slaves. Then East Africa mainly supplies slaves to the Arabic world (p.178). For instance, also Ethiopia has always been ruled by absolutist kings and emperors, which were active in a lucrative trade of slaves (p.232). Kongo is located in central Africa. In the west Mali, Ghana, Togo and Songhai can be mentioned (p.247). Also Angola deserves to be mentioned. The European supply of arms to the tyrants has increased the misery. For instance, at the start of the nineteenth century the British yearly sell approximately 300.000 rifles to West Africa.

During the eighteenth century approximately six million slaves have been transported across the Atlantic Ocean, among others to the Caribbean colonies. Inspite (or due to) the military power the African society is ravaged by a total disorder. The authors describe on p.249 that in Nigeria the oracle Arochuku was housed, which directly locked up many pilgrims and sold them to European traders. And when during the nineteenth century Europe and North-America forbid the trade of slaves, the African rulers again employ their slaves for themselves (p.251). It is clear that Africa has an extremely backward tradition, which has made economic developments impossible. Even the sad analysis of Boeke fails here. The society must be built up almost from the ground.

The colonization of the Third World at the end of the nineteenth century was unmistakably an attempt to further the economic development. However, the development aid starts only truly to expand after the end of the Second Worldwar. In 1945 the organization of the United Nations is established (in short UN). Other global institutions are also founded, such as the Worldbank and the International Monetary Fund (in short IMF). It is said that the period 1961-1970 is the first decade of development. After 1966 the development committee of the UN, chaired by the well-known Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen, tries to formulate goals for the second decade of development (in short DD2), which runs from 1971 until 1980. The committee publishes a report about these goals, and then Tinbergen writes the book Een leefbare aarde in an attempt to make the report popular5.

The present paragraph will summarize his most important findings. Even in 1970 still 75% of the population lives in the countryside. Tinbergen believes that the rapid expansion of the population is a serious problem - apparently little has changed since Boeke. According to Tinbergen the development cooperation is mainly a fight against poverty. Poverty leads to social polarization, to rebellion and to conflicts, and she threatens the peace. Violence and wars are frequent in the Third World. Tinbergen already predicts the international migration, which is made possible by the improvements in the passenger traffic (p.36). However, the development aid can prevent this. She must affect the four production factors, namely the natural resources, labour, the capital goods, and human knowledge. If desired, this can be expressed mathematically in a production function.

Tinbergen believes that the human knowledge is of central importance. Essential is a modern attitude towards labour, just like Boeke already stated. The population must be willing to make an effort for the improvement of her material wellbeing (p.65). This also includes the capability to take into account the future. In short, the valuation of the spirit of enterprise and of innovation is crucial. The people must be sufficiently tolerant to be willing to cooperate. This requires a certain self-control and disciplin. Reversely, the traditional law is not desirable for a modern society. Education contributes to a better attitude towards labour. Tinbergen focuses on this theme, because in the Third World the quality of labour is commonly miserable (p.74). And after reading the previous paragraph about the African society, this is understandable.

The rapid growth of the population has the consequence, that labour is abundant. Thus in the global competition the Third World has the comparative advantage, that it disposes of relatively cheap labour. Therefore in the global division of labour the Third World will have to concentrate on labour-intensive product branches (p.96). And for the domestic market it must choose labour-intensive production techniques. Tinbergen is convinced, that the Third World benefits from the reduction of trade barriers. Protection is only defendable in special situations, for instance when a state wants to further a new economic branch. Then she must be temporary. The international economic integration contributes to the welfare of all. The growth efforts do not necessarily require high profits. For, a rising wage sum increases the means of the state as well.

However, the optimal international division of labour does not form spontaneously. The states have to develop a plan for their economic structure. Tinbergen even advocates an international coordination of the division of labour (p.106, 164, 176). This confidence in centralization surprises somewhat, and can not be found in his previous publications. It almost seems as though here Tinbergen at the age of 67 years returns to the dogmatic ideas of his old mentor F.M. Wibaut. In addition Tinbergen prefers the mixed economy, which in principle consists of free markets. However, in some markets the product prices fluctuate to such an extent, that Tinbergen calls them unstable (especially the agriculture and mining). He wants to regulate them centrally. He also acknowledges, that for the time being the Third World has maintained elements of feudalism (p.112). Contrary to Boeke, he believes, that the political efforts can transform this system into capitalism (p.126).

Tinbergen bases his optimism on statistical data, which indeed show some progress in the Third World. Both the oil-producing states and the newly industrialising states in East Asia, with Japan on front, succeed in significantly increasing their welfare. The education improves and spreads, and even here and there the democracy is introduced. The Worldbank, which in former days restricted the granting of credits to building projects, now also finances education. The UN has a world food program, which redistributes food surpluses. However, Tinbergen wants to yet further expand the aid.

The report of the plan committee demands the member states of the Organization for economic cooperation and development (in short OECD) to transfer 1% of their gross domestic product (in short GDP) to the Third World, namely 0.75% by the governments and the remainder by the private sector (p.165). As far as the transfer consists of credits, they must have favourable conditions of redemption. In the long run Tinbergen even wants to increase these transfers to 2%. These are enormous sums of money, even for the rich OECD. They should be raised by taxation. Unfortunately Tinbergen hardly makes credible that thanks to this skimming of the OECD the Third World could indeed develop faster. Nevertheless, it is obvious, that such enormous sums of money can not simply be invested in a useful manner. He certainly ignores the possibility, that the aid could have an averse effect.

Furthermore, the aid must preferably be multilateral, so that the donor loses his say about its expenditure (p.158). In other words, thus the accountability with respect to the expenditure of the transferred capitals disappears. Tinbergen hopes that an international order will form, but this is hardly indicated by the present practices. In this respect he advocates the establishment of a global ministry of finance (p.192). Your columnist likes to comment here, that this form of aid opens the door for enormous squandering. Namely, the supervision of the expenditures and their evalution must be consigned to the UN organizations, where the Third World itself has an appreciable right of say. Considering the poor administration in many states the UN supervision does not look trustworthy. Besides, it is not clear, what must happen, when the Third World refuses to obey the directions of the UN6.

Two decades after Een leefbare aarde the volume A dual world economy, edited by the Dutch economists W. Adriaansen and J. Waardenburg appears7. It is worth summarizing its contents, because it reflects on the results of the first and second decade of development. In 1992 still 75% of the population in the Third World turns out to be active in the agriculture. However, the Third World itself changes, because thanks to the rising welfare more and more states leave this group8. After Japan the Asian tigers South-Corea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong have also become modern industrial economies. Whereas in the time of Boeke the Third World is still a homogenous block, in 1990 the picture is differentiated. There are industrial states, oil-producing states, states with a globally average income, and the low-income states of the traditional Third World.

An interesting phenomenon is the increasing urbanization in the world. The population moves more and more to the big cities, a development that Boeke considered impossible. It is striking, that the most successful states have commonly applied a policy, that encourages saving (p.26). Furthermore, in a middle group (Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Indonesia, etcetera) there are many direct foreign investments. Thus the growing urban population does find sufficient employment. Since 1960 the importance of development aid has diminished relatively (as a percentage of GDP). The experience shows that aid has a discouraging effect on the domestic willingness to save in the developing states (p.31). This shows, that dogmatic and one-sided attempts to fight poverty are rarely successful.

The need for an undogmatic policy of growth is precisely the message, that the well-known development economist H.W. Singer presents in his contribution to the book. For instance, Tinbergen has proposed the establishment of a global ministry of finance, because previously the Marshall aid to Europe was a strong stimulus for growth. However, an important condition for this approach is the presence of human capital (knowledge and skills) in the receiving state. And in the Third World labour is precisely of a miserable quality. When then the OECD transfers capital to the Third World, it can not find profitable applications (p.67). Nevertheless, especially during the seventies the Third World has acquired credits on a large scale, because at the time the oil dollars are abundantly available. Since then many of these states have accumulated a huge debt to foreign suppliers9.

A big problem of the Third World is maintaining the equilibrium of the balance of payments. In principle this can be solved by protecting the domestic industries by means of import restrictions. However, this encourages laziness of the industries. Singer believes that the Third World benefits most from the development of an export industry (p.69). However, this requires a good attitude towards work, a skilled administration, and an appreciation of entrepreneurial spirits. The modern development aid values the accumulation of human capital as a high priority of policy (p.76; as the reader knows, Tinbergen also considers the human behaviour as an indispensable production factor). But the agriculture must also be modernized, so that her productivity rises. In the past, this has received insufficient attention, at least in the Third World, because the OECD states did always invest in their agriculture.

In 1992 the Third World is already mainly reduced to sub-Sahara Africa. The labour-intensive production is still considered to be the best way to compete internationally. In this view the small-scale agriculture can be maintained. Nowadays, planning, resulting in a structure policy, as proposed by Tinbergen, has lost its appeal (p.86). Planning discourages initiative and participation (p.95). On the other hand, Singer states, that the structural adaptation programs (in short SAP) of the IMF aim too much at the liberalization of the economy. The Belgian economist L. Cuyvers states in his contribution to the book, that in the emerging states a significant part of the new employment is created in the sector of services (p.172). This contradicts the old idea, that modernization can merely proceed by means of industrialization.

Cuyvers als advises the developing states to export their goods, because export stimulates an efficient production, and moreover reduces the production costs due to advantages of scale. However, the present Third World states can not simply imitate the growth trajectory of the Asian tigers, because since then the global rate of growth has slowed down. The postwar period of the golden thirty years is over, and therefore also the huge demand for products from the Third World. Nowadays the export-driven growth requires much more effort (p.188). The Dutch economist H. Verbruggen also sees many advantages in export, such as the accumulation of knowledge (p.198). It will be accompanied by a gradual opening of the domestic economy. Finally, P. Terhal advocates the formation of a civil society, that consists of various interest groups. Thus she becomes a countervailing power with regard to the state and the industries10.

Acemoglu and Robinson mention in their book Why nations fail several conditions, which must be satisfied for the development of a state. Solid institutions are essential for a successful economic development11. They must be inclusive, that is to say, everybody must be able to participate in the economy and in politics (p.87). In such a society everybody can start their own enterprise, and that leads to innovation and creative destruction. And innovation is an indispensable element for furthering a durable economic growth. The political inclusion is necessary, because in modern capitalism politics determines the shape of the economic institutions (p.49). And in a democracy the citizens control politics. The political process is the key to success (p.73).

Systems that limit freedom are called extractive (p.81). Then there is an elite, that possesses all power, and that does not accept an external competition. This type of systems often suffers from a power struggle within the elite, because that is yet the only possibility to enlarge one's own wealth (p.152). In a state without inclusive institutions development aid merely has a limited positive effect (p.433). Here the reader probably recognizes the plea of Tinbergen and Singer in favour of an increase of human capital.

According to Acemoglu and Robinson the transformation to an inclusive system is by no means simple, because luck plays a role. Namely, transformations towards inclusion emerge only during crucial historical phases, during an unexpected window of opportunity. When then the institutions are reformed, these generate an institutional drift (p.112, 415). That is an upward spiral, that makes the institutions more and more inclusive. Unfortunately, downward spirals back to exclusive ones are also conceivable.

In 1995 the politicians M. van den Berg and B. van Ojik wrote the book Kostbaarder dan koralen, by order of the Dutch development aid organization Novib. In 1998 the same authors published the sequel De goede bedoelingen voorbij12. In these two books the authors describe the changing ideas about the economy in the Third World, and in particular about the development aid, from the perspective of a private aid organization. They state, that since the seventies the aid could rely on a broad social support within the Netherlands. However, during the nineties the scepsis about the positive effects of aid increases. Help seems to improve the situation in a Third World state merely, when the policy of the state is sound. Besides, the operation of markets is seen as an essential condition for development (as has already been shown in the paragraph about the views of Acemoglu and Robinson)13.

During the sixties help still aimed at the stimulation of growth. However, Van den Berg and Van Ojik believe that the economic growth is only beneficial, when in addition the society becomes more egalitarian. And indeed during the seventies the policy shifts to the satisfaction of the basic needs in the population. This is a policy, which Jos de Beus called kind equality, and which is also embraced by the authors. Therefore they criticize the approach during the eighties, when the operation of markets, competition and liberalization are recommended. The oligopolies of the big industries and banking dominate on the markets. These enterprises undermine the development in the Third World (p.44 Dgbv). Thus the authors yet seek the cause of the global poverty in the OECD states. They want to complement the policy of markets with a fight against poverty14.

According to the authors, South-Corea is a classic example of a sound development. That state obtained much international aid, and moreover the state intervened in the economy. Essential basic needs are a broad education, care, and the protection of human rights. Therefore it is desirable to create a civil society in the Third World. This requires lots of money. The authors turn again to the ideas of Tinbergen, and want to collect global taxes. The yield must be controled by the United Nations, that can pay a global social security from these funds (p.112 Dgbv, p.27 Kdk). Here your columnist notes, that the collection of taxes is the prerogative of the state. Since the UN are not a world government, such a fund invites waste and abuse.

All in all, the authors substitute the fight against poverty in place of the plea of Tinbergen for economic independence and growth (p.87 Kdk). The public sector must expand again (p.62 Kdk). They hope that education can lay the foundation for a better government. This implies that states with a corrupt government must still receive aid (p.74, 106 Kdk).

Especially in Kostbaarder dan koralen the authors still use the model of a participative democracy. The Third World states must get a bigger say in the aid programs. On p.21 they even conclude, that those state can stonewall by blocking the global environmental policy. Incidentally, migration is also a means to incommode. The donor states intensify the control on the use of aid, and the authors interpret this as a restriction on the autonomy of the Third World (p.82, 87). Your columnist notes, that during the seventies New Left experimented with the participative democracy, and that this failed in the west.

Development aid has many forms. Western donor states commonly give a part of the aid to special projects, that aim at specific development themes. This kind of aid also subsidizes the export of the Dutch industries to the Third World. Furthermore, there is bilateral aid, often in the form of state programs. And finally, there is the multilateral aid, where the expenditure is delegated to international agencies15. When an aid program is put out for tender, then non-governmental organizations (in short NGO's), such as Novib, Caritas, Hivos, The Red Cross, Physicians without borders, etcetera, can react with an offer. So actually a market for development aid has been created16. The activities of the NGO's on this market give an interesting impression of the functioning of the economy in the Third World.

Some states are even totally dependent on aid. For instance, halfway the nineties the aid to Tanzania was 33% of its GDP, to Nicaragua 50%, and to Mozambique even 70%. The book De crisiskaravaan by L. Polman describes the working methods of NGO's in various Third World states17. She concludes that reporters rarely write critically about aid, among others because the trip and the stay are paid by the concerned NGO. Polman wants to highlight in her book some dark sides of the aid branch. She stresses, that the NGO's are normal enterprises, which depend for their existence on the acquisition of aid contracts. Thus the NGO's are forced to picture the progress of their projects in a possibly favourable manner. When a project fails or leads to waste, then this will often be concealed for the donor and the media.

On the other hand, the attention of media is essential for the NGO's, because politicians often react by making available extra funds. The NGO's try to make the TV pictures and press reports very spectacular. Usually the concerned Third World state (the beneficiary) supports this enthusiastically. Once a contract has been signed, the funds will be spent completely, even when the effects turn out to disappoint. On the spot in the aid area the NGO's advertise for their presence, by abundantly showing their logo. This is only omitted, when the local situation is too unsafe. The local government commonly skims an appreciable part of the aid. In emergency aid this can add up to 80% of the total budget (p.97, 120). The NGO's accept this waste, because the remainder does reach the target group.

The NGO's themselves are sometimes inefficient as well. Polman describes a project in Afghanistan, where a western NGO hired other western NGO's as sub-contractors. Thus 60% of the fund was spent in the western head-quarters, even before a start was made with the development aid on the spot (p.143)18. Incidentally, the NGO's are competitors, and therefore they are usually not willing to support each other.

Once one ponders over the preceding text, the conclusion seems obvious: the economic development depends strongly on the right attitude towards labour and on the spirit of enterprise. Education, care and sufficient food contribute to a beneficial atmosphere for entrepreneurs. Therefore, since the Second Worldwar a transfer of capital from the OECD member states has been advocated, in order to realize such basic facilities in the Third World. However, during the eighties the notion spread, that such aid can be counterproductive, because it fosters laziness, love of ease, and abuse in the Third World. Henceforth it is preferred to combine the development aid with the operation of markets. The Third World must learn to export. The planned development in South-Corea and Japan can no longer be copied, because in the mean time the global competition has become more fierce.

Originally this change of policy lead to resistance from the NGO's and the leftwing politicians, especially in the Netherlands, since they preferred to realize socialism in the Third World. They believed that a dominant state is indispensable for a sound rule. However, this resistance has weakened, partly because nowadays the NGO's themselves also compete on the market for development aid. The implementation of central planning in the Third World has been abandoned. The domestic administration is usually too miserable for planning, and besides it hinders the economic integration. Henceforth the Third World must produce for the world market in order to acquire foreign currencies. Here it has the competitive advantage, that it can employ a labour-intensive production with low wages. And the markets of the OECD states become more accessible, because they reduce their import 19.