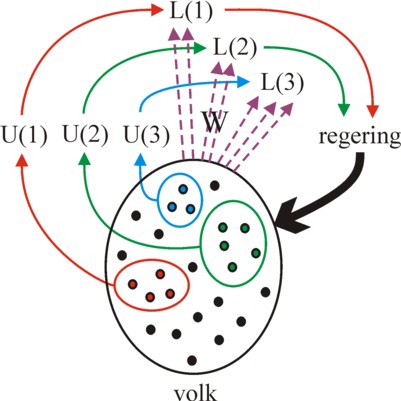

Figure 1: Communication flows in

pluralism

U(k) = target function; L(k) = leader k;

W = choice function of voters

Any society controls the human behaviour by developing her own morals. The morals also affect the economy, and partly determine its efficiency and the social welfare. Nevertheless, little is known about the formation of norms. The present column explains norms by means of the rational choice paradigm. For this purpose the value rationality is analyzed. It is explained how norms can be enforced. An obvious method is sanctioning, but internalization is also conceivable. Various mathematical models are discussed.

Since over a year the Gazette regularly publishes columns about political economics. That is not due to a diminishing interest in economics, because this continues to fascinate your columnist. The broadening of the material is simply caused by the undeniable fact, that politics partly controls the development of markets. Those who want to understand economics, must gain insights in its social embeddedness1. Besides, your columnist has been imbued with an interest in state interventions, like those that the traditional social-democracy propagated. In this respect one may remember the rather extreme Leninist experiment, which has put its mark on the twentieth century, and completely integrated the economy and politics. Thus the Gazette has already in a column of 2013 reflected on the interaction between the social factors and the economy.

This early column of 2013 introduces two interesting thinkers, namely the economist Paul Frijters and the sociologist Heiner Ganßmann, who set the tone for the later discussions in the Gazette. Frijters and Ganßmann state, that markets do not completely conform to the ideal picture, that liberalism traditionally attributes to them. On the contrary, markets have many deficits, which lead to a desintegration of the system, unless they are curbed by a supervisor. By now it is generally known, that markets cause many external effects, that is to say, unintended side effects on various social groups. Next those groups must defend their own interests, and that can commonly not be done by means of market processes. The starting point of all market regulation remains the collective organization. First of all, she leads to the establishment of the state.

The state promulgates laws, such as the criminal en civil laws, which regulate the actions of citizens. Thanks to its monopoly on violence the state can enforce this laws against various interest groups. Since due to the state power, politics can intervene with corrections, this legitimizes its existence. Unfortunately it is extremely difficult to manage markets in an effective manner, because the operation of markest is still poorly understood. Despite attempts of analysis, the macro-economics, the society, the culture, and politics remain a black box. The state is in principle also a body at the macro level. In the modern industrial states, at first the control was conceived in the form of a central plan. Our compatriot Jan Tinbergen has done ground-breaking work in the science of planning. However, the experiences show, that this instrument is much too rigid and primitive for satisfactorily solving the market failures.

Therefore, halfway the twentieth century the economic scientists began to search for more refined instruments of economic intervention. Thanks to the scientific progress there finally grows some understanding of these collective phenomena, namely by truly starting the analysis at the micro level of traders and enterprises. This approach is called the methodological individualism2. The starting point for this relatively new method remains the image of man as a homo economicus, which already dominated the classical economics. The homo economicus is a calculating actor and an egoist pur sang, only motivated by his own survival. However, he wants to protect himself against the externalities of his companions, and he finds this countervailing power in the collective organization.

The intriguing question is how man as a natural individualist is capable of establishing such collective bodies. For, man as a homo economicus aims at maximizing his own utility or satisfaction. The present column wants to sketch the direction, where science hopes to find the answers3. An important scientific break-through is the so-called rational choice theory (in short RCT). According to the RCT the satisfaction ui of an actor i can be represented by the formula4

(1) ui(ci1, ci2, ..., ciM, t) = Σj=1M xji × ln(cij(t))

In the formula 1, cij(t) is the quantity of the good j, which the actor i owns at the time t. The parameter xji is a positive constant, which indicates the need of the actor i for the good j. The formula 1 shows that markets can be regulated. Bodies at the macro level must promulgate laws and rules, that affect the quantities cij(t) in such a manner, that the externalities of the individual actions become positive for society as a whole. The assumption of the individual optimization of utility implies, that the actors behave rationally, so that regulation has a predictable effect. This is called instrumental rationality, or also consequentialism. This model of the RCT turns out to be scientifically fertile, and has lead to many new insights.

Nevertheless, the RCT can not be the final word. For, the formula 1 suggests, that the preferences and needs of the individual are stable. His motives are fixed by the constants xji. However, in reality each individual i undergoes a continuous development during his life, so that his nature xji adapts to his environment. The experience shows that this adaptation can also be beneficial for the individual, and as such it can be rational. However, the adaptation can no longer be explained by the instrumental rationality. Therefore, it is distinguished by calling it value rationality, or somtimes axiological rationality5. This kind of behaviour affects the personal norms and values of the individual. It is far-reaching, and sometimes outright painful, because the personality is partly abandoned. The collective interest enters in the individual utility. Here Frijters uses the term love.

As an illustration of value rationality it is interesting to reconsider a previous column about the ideology of the social-democracy. There a model of communication flows in a society with pluralistic politics is presented. The model is depicted graphically, and for the sake of convenience it is copied in the figure 1. It is clear that in the state the individuals organize into various interest groups (hence pluralism). In the organization of type k the individual utility functions of the formula 1 are transformed into a collective target function U(k). A leader L(k) is appointed, who must propagate the target function, for instance in a political coalition. When the democracy is representative, then the citizens determine together in an election the composition of the coalition. Thanks to the election the individual utility functions W of the non-organized citizens are also represented.

Both the organization of individuals and the election are processes, which from the micro level control the macro level. Now, for the present column about value rationality the thick black arrow in the figure 1 is relevant. For, it represents exactly the reverse communication flow: the control of the macro level on the micro level. It is precisely this flow, which allows to regulate the behaviour of the individuals, among others on the economic markets. The leader L(k) formulate together a government policy. Here the policy measures can target both instrumental rationality and value rationality. In the first case, the individual adapts his actions to the policy, because thus his utility increases. This changes his quantities cij(t). In the second case, the individual adapts his norms to the policy, which changes his preferences xji(t). Thus the individual i changes the structure of his own utility function ui.

The instrumental rationality can be modelled fairly simple with as the starting point the individual, who maximizes his utility. Previous columns in the Gazette have illustrated this with various examples. However, value rationality has a more complex character. Therefore she is discussed in a separate paragraph.

The present paragraph discusses three views on value rationality, of the sociologists R. Boudon and J.S. Coleman, and of the economist P. Frijters. Boudon gives a presentation, which is rather philosophical, and of limited practical importace. Nevertheless, she proposes an interesting frame of thought. Boudon complains about the "black box" approach, which is fairly common in the human sciences. It states that human actions are prescribed by the actual boundary conditions (the box), such as human nature, culture, or various historically grown institutions. Thus it is true that reality is described, but an explanation of the box itself remains absent. Boudon argues, that developments can always be attributed to logical causes. He states that famous sociologists such as Alexis de Tocqueville, Max Weber and Emile Durkheim all base their analysis on human rationality. Boudon is a true advocate of the RCT.

However, he acknowlegdes that it is difficult to apply the RCT to actions, that are dominated by value rationality. He wants to analyze such situations with the concept of the objective observer, which originates from the famous English moral philosopher Adam Smith. This simply means, that individuals can judge the reality in an impartial manner. Thus for each problem a single solution is the best one. And man can choose that solution. Following Emile Rousseau, it can also be said, that a universal will exists. Therefore logical causes can be identified for all human norms, values and laws and regulations. It is the task of science to reveal this rationality in the social developments. Boudon calls this scientific approach somewhat pretentiously the general theory of rationality. The RCT is a special case of this, namely when the rationality is instrumental.

Boudon maintains the principle of the RCT, that phenomena at the macro level must be explained from the individual actions at the micro level. According to him, rationality is "common sense", in ordinary life just as well as in science6. Therefore a decision is sometimes based on justice or fairness, and not on an optimization of utility. Although the frame of thought of Boudon is interesting, your columnist also sees difficulties. First, various alternative explanations of a phenomenon can all seem equally logical. Then the best one can not be chosen. For instance, Boudon propagates liberalism, although yet many have other political preferences7. A common objection against the general theory of rationality is the difficulty to test her in an empirical manner. Therefore, it will now be assessed, whether perhaps the theory of Frijters is more promising.

Norms and values are not per se a phenomenon at the macro level, but is seems obvious that they are collective. They obtain meaning, because they are shared with others. Now the question is, how individuals are motivated to internalize norms and values. Frijters proposes as an explanation, that individuals by nature are inclined to exhibit feeling of love towards groups. This is even partly a subconscious process. Love implies that the interests of others are included in the personal utility function. Love is a form of socialization, which sometimes requires some group pressure. Then the entrance of the individual in the group starts with a phase of initiation, which "demolishes" the old utility function. Next the utility function is rebuilt by the internalization of the group norms8. The individual expects that his love will yield a reward. It is an investment.

Participation in a group has several advantages. In other words, she is a social capital. According to Frijters, usually only a group can exert power (although wealth is also a factor of power)9. And the group promotes the interests of her members. The group can punish, but also reward. Thanks to the size of the group, the individual risks can be shared. The group accelerates learning processes, and furthers that the most effective behaviour is imitated. Conversely, it allows for the division of labour. In general groups behave more rational than individuals. Thus it can be imagined, that the inclination to show love is formed in an evolutionary process. It is true that man as species is very suited for this, because he disposes of capabilities of cognition.

Incidentally, each individual is a member of various groups. The groups themselves are again a part of larger groups. Groups continously interact with each other and negotiate, just like individuals. Thus actors from outside the group can exert influence, and in this way force the group to change its norms and values. This is a process from the micro level to the macro level, because it makes the group adapt to society. Thanks to this process, there is social progress10. Frijters believes that the nation state is formed during a long process of group formation11. Thus Frijters presents a model, which is more concrete than the approach of Boudon, because each decision relies on the maximization of utility. Frijters does not need to refer to vague concepts such as fairness or the common sense. However, a further improvement is possible, because the model of Coleman does not explicitely need love.

Coleman concludes that group structures are useful for all. They allow for all kinds of beneficial exchanges. Thanks to the mutual communication agreements can be made, perhaps in the form of norms. According to Coleman two phases are needed for the creation of norms12. It is obvious that the norm must be wanted, for instance as a consequence of a negative external effect. Besides, the norm must also be enforceable. Thanks to an accepted norm, the control of the individual actions is delegated to others than the individual himself. Furthermore, Coleman points out, that the enforcers of the norm are not necessarily the same as those, who are subjected to the norm. In that case he calls the norm disjoint. The enforcers are commonly the individuals, that benefit from the norm. When the enforcers are also the subjects, then the norm is called conjoint.

Coleman distinguishes between three ways to enforce the norms, where the first two use instrumental rationality, and the last one uses value rationality. First, the norm can be enforced, simply because it gives socially the highest yield. The enforcers attach so much value to their norm, that they can buy the ownership of the undesirable action13. The second manner implies, that the enforcers sanction the actor, so that the undesirable action will no longer be beneficial. However, sanctioning causes costs for the enforcers, so that the benefit of the norm may be undone. On the other hand, the costs can be divided among the whole group of enforcers. When this is possible, then henceforth the enforcers as a group control the concerned action of the subject. They own the control.

Finally, the third way is to manipulate the actor in such a manner, that he is willing to internalize the norm. Then the actor will integrate the utility of the others into his own utility function. Typical forms of manipulation are education, propaganda, or group pride. It is true that the costs of the manipulation are high for the enforcers, but they are made only once, and next the enforcement can be left to the subject. Moreover, these costs can also be divided among the whole group of enforcers. This manner could be called socialization, and closely resembles the process of love, that has been suggested by Frijters14. Furthermore, Coleman proposes an interesting abstraction of the process, where he cleverly applies existing psychological insights.

Namely, the actor continuously weighs his utility by means of his objective Self15. The objective Self is formed in the interactions with his closest relatives, Thus parts of important others, such as parents, teachers, class mates, colleagues, political leaders etcetera, are integrated in a natural manner. This is accompanied by an internalization of their interests. The individual adapts his own goals and interests to the rest. The Self mirrors the world. This is notably convenient, when the costs of the individual for changing his relatives would be high. Everybody competes with an internal and external world. This view pleases your columnist somewhat more than the love according to Frijters. Due to its high level of abstraction and rationality it seems more amenable to analytical models, although Coleman himself did not invent any. A difficult problem is, that the modelling of the internalization requires a dynamic utility function.

Coleman also refers to the balance theory from the social psychology16. That theory states that individuals have the natural inclination to reduce internal conflicts and tensions in their own world of thought. Thus, when an internal norm causes external rejection, then it is advantageous to adapt the personal system of norms in such a manner, that the rejection will weaken. Your columnist is excited about the inter-disciplinary bridge, that is constructed here between economics and psychology. But unfortunately no method is known for applying this model to situations of economic activities, that generate social consequences. This must also be the conclusion of this paragraph. Boudon is not very helpful. Frijters and Coleman suggest valuable insights for the influence of the macro level on the micro level. But unfortunately they do not supply an operational model.

In short, a clear concept for curbing markets is still missing. But the present paragraph at least shows, that even the human ethics and morals can be explained as a rational phenomenon at tht individual level. It also turns out, that rationality is not a protection against group pressure. Those who possess much power, can discipline others. This shows that morals are relative, because apparently the individuals are willing to opportunistly adapt their ethical principles, if required. Your columnist sees here a beginning towards a deeper insight17. The remainder of this column illustrates the preceding arguments by means of several mathematical models, for the true connoisseurs. First, a mathematical model of Frijters is presented, and then several models of Coleman.

Frijters has summarized his views on group processes in a mathematical model18. This model fits nicely with the view of Coleman. The present paragraph discusses several important aspects of the formalism. The starting point is a system of N individual actors, who are organized in K groups. Frijters assumes that they can join just one group. So there is exclusion, such as in the figure 1. A group has Nk member, with k=1, ..., K. Each group establishes its own norms, and the group members are willing to enforce those norms. As soon as an actor i (with i=1, ..., N) breaks a group norm, he will get a fine, which is a cost for him. Consider a certain time period. In that period each actor j (with j=1, ..., N) can impose a fine of vji on the actor i. Conversely, the actor i himself can impose fines vij on the other actors j.

Apparently the actor i concretely links with a group of a set of actors, which is symbolicly represented by Si. Now Frijters states that the utility of the actor i is given by

(2) νi = ui(yi) − β1 × Σj→N vij − β2 × Σj←Si vji − β3 × Σj→Si vji

The formula 2 requires an explanation. The term ui(yi) is the static utility, which is defined in the formula 1. For the sake of convenience, here the possessions cim are replaced by the aggregate income yi. The Σ symbol is the well-known mathematical representation for a summation. In the formula 2 the sums run over all elements in a certain set. Here → means "is an element of" and ← means "is not an element of" 19.

Consider the second term in the formula 2. These are the fines, that the actor i himself imposes on the N-1 other actors. The imposition of the fine is a burden for i, so that his utility νi diminishes. The parameter β1 is a scaling factor, which determines the costs of the imposition of the fine vij for i himself. The third and fourth terms are fines vji, that the N-1 other actors impose on the actor i. The third term describes the fines by actors j, who are not a member of the group Si. The fourth term describes the fines by actors j, who do belong to the same group Si as the actor i. Note that each actor has the same scaling factors β1, β2 and β3. Frijters assumes, that 0 < β1 < β2 < β3. In other words, receiving a fine is worse than imposing a fine. And a fine from the personal group is worse than a fine from outside. The last three terms in the formula 2 introduce the group dynamics in the utility function.

The formula 2 strongly suggests, that the group dynamics has a negative effect on the individual utility νi. It seems that it reduces νi. However, the group formation is indeed rational, because she augments the income yi of each actor i, and thus also ui(yi). Besides, there is a redistribution, which can be interpreted as taxes and benefits. Each actor determines how much taxes and benefits he will pay. Frijters believes that the incomes are so important, that he analyzes only norms, that concern redistribution. Therefore the imposition of a fine is always an attempt to correct and manage the tax remittances of the actors. Frijters supposes that the redistribution is characterized by the tax rate, that is to say, by the fraction of yi, that is paid as taxes.

Suppose that the actor j pays out a benefit to i, which matches a tax rate τij. The actor i will usually prefer a different distribution. He will believe that actually a tax rate σi,Sj is fair, for all actors in the group Sj. First of all, he demands the benefit for himself, and for reasons of solidarity will demand the same benefit for the other members of his group Si. Thus group power emerges. When an actor j breaks his norm, the actor i will show his anger with a fine vij. It is remarkable that according to Frijters a breach is absent, when the actor j pays more than i prefers. Now in formula the fine is expressed as

(3) vij = αi × (f(σi,Sj − τij) + γi × Σh→Si/i f(σi,Sj − τhj))

In the formula 3 f(t) is a function, which rises for an increasing t. When t≤0, then f(t)=0 holds, so that no fine is imposed. And Si/i represents the group Si without the actor i himself. Thanks to this split the solidarity or love of i with regard to his group is expressed. An egoistic i has γi<1, whereas a heroic i prefers γi>1. Incidentally, Frijters expects, that heroism is absent. The parameter αi expresses, that i is indignant at the supposed injustice. Suppose that ζi is the distribution of income, which precedes the levying of taxes. Then the distribution after taxes equals

(4) yi = ζi − ζi × Σj τji + Σj ζj × τij

Now the actors choose a social system by each of them maximizing his own utility νi. The formula 2 shows, that this is a complex problem. For, the actor i can vary both yi and vij, and in addition the reactions vji of the others must be taken into account. The formulas 3 and 4 show, that at a somewhat deeper level the actor i must decide about the norms αi, γi, and σi,Sj, that he wishes to support (the objective Self), and about the taxes τji, that he is willing to pay (the acting Self). The aggregated choices of the N actors lead to a social equilibrium. This completes the model. Its merit is that a long narrative is condensed into a few formulas. Nevertheless, it is also clear, that the model is quite abstract. And although Frijters elaborates the model for a few special cases, the road towards practical applications seems long.

Coleman illustrates his theoretical argument about norms with several clarifying examples. They will be copied in this paragraph. Consider a social system with three actors, say A1, A2, and A3. Each of them is requested to support a project with a gift with a value of 9. The project promises a profit rate of 1/3. However, the yield of the project will be distributed equally among all three actors. Apparently it is a public good, which does not allow to exclude anybody. Let Gj be the gift of actor Aj. Then his profit is given by Wj = -Gj + Σk=13 (Gk + Gk/3) / 3. Now each of the actors must decide in isolation whether he will contribute to the project. The table 1 presents the profit, that each of the actors receives, dependent on their decisions. This manner of analyzing exchange processes is called game theory.

| A3 contributes | A3 does not contribute | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 contributes | A2 does not contribute | A2 contribute | A2 does not contribute | |

| A1 contributes | 3, 3, 3 | -1, 8, -1 | -1, -1, 8 | -5, 4, 4 |

| A1 does not contribute | 8, -1, -1 | 4, 4, -5 | 4, -5, 4 | 0, 0, 0 |

It is clear that each actor must make a difficult choice. It is socially desirable that all actors contribute, because then the total profit Σk=13 Wk is maximal, namely 9. Then each actor obtains a profit Wj=3. However, when the individual actor does not contribute, then he has a fair chance to obtain a profit of 4 or even 8. In this situation each of the actors does behave rationally by not contributing. Thus the total profit becomes Σk=13 Wk = 0, which is a sub-optimal result. Apparently there is a social need for a norm, which obligates everybody to contribute.

Suppose that the actors A1 and A2 simply contribute, but the actor A3 does not. Furthermore, suppose that the project is repeated regularly. Then the free riding of A3 can be observed by A1 and A2. As long as an enforceable norm is lacking, A1 and A2 can only punish A3 for his action by refusing to contribute as well. This threat may stimulate A1 to yet contribute. Note, that it does not suffice, when merely A1 threatens. For, it is true that this would reduce the profit of A3 from 4 to 8, but that is still more than 3 (the outcome of contributing). Apparently it is necessary that A1 and A2 coordinate their threat.

Coleman tries to find a more attractive manner of enforcing the norm. He ignores the possibility of internalization. It seems obvious to organize the norm in such a manner, that a breaker is immediately punished with a fine. The fine must have a value of 5, because this reduces even the highest profit of 8 to 3. This fine will make it profitable for the breaker to henceforth contribute. However, there are costs attached to the introduction of a judicial body, which imposes the fines. In the formula 2 of Frijters only the actual imposition of the fine on j causes costs vij. However, Coleman assumes, that the costs are "fixed". That is to say, the establishment of the body itself has costs with a value of 5, which must be borne, even when the actor j obeys the norm. It is a coincidence, that here those fixed costs are identical to the imposed fine20.

Unfortunately this manner of enforcing has a problem. Namely, suppose that A1 pays the establishment of the body. This costs him 5, whereas enforcing the norm brings him merely (3 − (-1) =) 4. A1 would suffer a loss. Apparently the body can only be realized, when A1 and A2 share the costs. In other words, A2 must give a reward (positive sanction) to A1, so that he will establish the body. For instance, A2 could subsidizy half of the costs, namely 2.50. The interesting point is that in this way a new problem from game theory is introduced, albeit with just two actors. The various choice alternatives are presented in the table 2. The outcomes in the table 2 are the sum of the outcomes in the table 1 and the costs of the body. The enforcement of the norm by the body is a public good. Therefore Coleman calls this game a public good problem of the second order.

| A2 subsidizes | A2 does not subsidize | |

|---|---|---|

| A1 subsidizes | 0.50, 0.50 | -2, 3 |

| A1 does not subsidize | 3, -2 | -1, -1 |

It is clear from the table 2, that the enforcement of the norm is viable, because the yield is larger than without norm. Nevertheless, there is a temptation to shift the costs of the body to the other actor. Coleman does not clearly address this dilemma22. Apparently, for instance the actor A1 must threaten, that he only subsidizes the body, when A2 does the same. Or from another perspective: actor A2 understands that he must encourage A1 with a reward (positive sanction) to pay the body. Furthermore note, that the risks in a game of second order are less than in the game of first order. When an actor breaks the norm in the second-order game, then this costs the other (0.50 − (-2) =)2.50, whereas a break in the first-order game costs (3 − (-1) =)4 to the other(s).

Coleman has developed a model, which allows to calculate for a given system the social support for a prohibitive norm23. To be concrete, it concerns a situation, where the actor 1 wants to execute a project, that promises him a profit. However, the project has a negative externality, so that the other N-1 actors will suffer from it. Therefore they need a norm, which forbids the project to all. Therefore the norm is conjoint. Apparently the system can be in two different states. In state A the norm is not commonly supported, so that actor 1 is free to execute the project. And in state B the norm has sufficient support for prohibiting the project.

Here there is actually a conflict of interests. Both the actor 1 and the other N-1 actors try to gain control over the project. Whoever has the control, determines what the state of the system becomes: A or B. That is to say, there is a conflict about the ownership of the project, and those who want to pay most will acquire it. The outcome of the conflict follows from the value of the project for actor 1, and from the value for the other N-1 actors. Suppose that for the actor 1 the project p in state A has a value vpA, and for the N-1 actors the project in state B has a value vpB. Only when vpB > vpA holds, then the norm has sufficient support. For, then the N-a actors are willing to compensate the actor 1 for the loss, that he suffers due to the norm. Thanks to the compensation the actor 1 will abandon the project.

Coleman applies the formula 1 for the calculation of vpA and vpB. The quantities cij together form an N×M matrix, and the interests xji form an M×N matrix. For the sake of convenience, Coleman prefers to normalize C and X in such a manner, that one has Σi=1N cij = 1 and Σj=1M xji = 1. In a previous column it is explained that for such a linear system of actions the value vj of the good j can be calculated. Note that this is a vertical vector. It turns out that one has24

(5) v = (I − X C + E)-1 η

In the formula 5, I is the M×M unit matrix, E is an M×M matrix with elements ejk = 1/M, and the vertical vector η has elements ηk = 1/M. The ownership of the project p at the start (time t=0) is expressed by the column cip in the matrix C. The interest matrix X differs for the states A and B. For, in the state A the actor 1 executes the project, and only he has an interest in it. Thus xpiA = 0 for i unequal to 1. And in the state B the project is prohibited, and the actor 1 has no interest in this. Thus xp1B = 0. The two interest matrices are represented by respectively XA and XB. As an illustration of this model Coleman works several examples, which your columnist copies here. There are three actors (N=3), and four goods (M=4). The project p is the fourth good (p=4). The table 3 gives the numbers, that Coleman uses.

| C | XA + | XB + | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j= | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| i=1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.255 | 0.085 | 0.15 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 |

| i=2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.1 |

| i=3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.1 |

| v | 0.398 | 0.282 | 0.249 | 0.07 | 0.429 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.052 | ||||

Note that the table 3 contains the mirrored matrices of XA and XB. This is indicated by the index +. Their elements are xij. The aim is merely to simplify the grouping of the table. Coleman has chosen a simple matrix C. At the start he makes the actor 1 the owner of the project p (j=4). It seems as though the matrices XA and XB are very different. However, in reality the interests in the two X matrices are equal, with the exception of the interests for the project. The differences occur purely from the normalization Σj=1M xji = 1. If desired, the reader can verify this by himself. In the lowest row of the table the value system is calculated by means of the formula 5, for the states A and B. It turns out that v4A = 0.07 is larger than v4B = 0.052. Thus the actors 2 and 3 can not buy the project from the actor 1. The prohibitive norm is untenable.

This can be explained as follows. It turns out that one has v = X r 25. That is to say, the value of the good increases according as its interests increase, or according as the richess behind the interests increases. Therefore it is conceivable that under modified conditions the norm does receive sufficient support. For instance, Coleman calculates, that in case of a reduced interest of actor 1 (namely x41 = 0.1) the value v4A falls to 0.046. Therefore the introduction of the norm becomes efficient. Coleman also shows, that it matters who at the start owns the project. Suppose that the ownership is attributed to the actors 2 and 3 (c14=0, c24 = c34 = 0.5). Then one has v4A = 0.057, and v4B = 0.060. Thus the norm is again tenable. The reason is that the ownership of the project gives more power rj to 2 and 3.