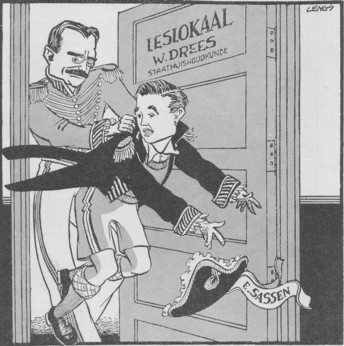

Figure 1: Drees teaches economics

Caricature by H. Lengs (1949)

Source: De Nieuwe Eeuw

During the eighties the original ideology of the social-democracy failed ineluctably. Perforce the social-democratic parties have transformed their programs into the radical centre (Third Way, Neue Mitte). Subsequently the radical centre has been very successful in elections. The present column analyzes the politics of the radical centre. Its hallmark is pluralism. The variants in England and Germany get special attention. They are compared with the Van Waarde project in the Netherlands.

In roughly ten columns the Gazette has described the economic history of the Dutch social-democracy, from its early rise until the present, with sometimes a detour to her foreign congenials. This attention for the social-democracy is justified, because she (together with corporatism) is the only current, that seemed to offer a credible alternative for liberal capitalism. Especially at the start of the twentieth century she was a source of innovative social ideas, with a ready blueprint for a new economic system, which claimed to offer a solution for the existing problems. The core of the blueprint is the expropriation of enterprises.

At the time there was a social consensus, that liberal capitalism could not be durable, because it does not succeed in solving the social question. That is to say, the industrial workers live in degrading conditions, and their situation hardly improves, despite the economic growth. Their fate is in glaring contrast with the situation of the entrepreneurs, such as the urban bourgeoisie and the peasantry. This causes severe social tensions. In this situation the willingness to radically reform the society increases, notwithstanding the huge social costs. The socialist ideology became popular in some intellectual circles. Incidentally, there was not much awareness of the costs, that a revolution entails. For instance, there was still much appreciation for the French revolution, although she and her aftermath were fatal for Europe.

The doctrin of the socialization was so convincing, that after 1917 Russia has indeed realized it, although this required an extremely violent revolution, resulting in a civil war, that lasted for many years. It turned out that she was a historical mistake, which imposed a horribly high price on the Russian people. However, due to the then coup d'état of the Leninists, the socialist doctrin did get the opportunity to prove itself. And it has lost the system battle with liberal capitalism. Soon, during the thirties, the western congenials of Leninism recognized, that the early doctrin of the social-democracy is unsound. Moreover, gradually the motivation for that rigourous revolution disappears, because capitalism is supplemented with social security. However, an existing movement can not simply discontinue itself, and therefore the social-democracy has continually tried to revive herself by means of new ideas.

The next find of the social-democracy is the planned economy, which maintains the private property. This attempt is similar to corporatism. The socialization does not concern the property itself, but merely the control of the property. Nevertheless, the planning ideology has never incited the enthusiasm, that emerged earlier for socialization. The social question can be solved within capitalism, and due to the scientific progress the high costs of revolutions become apparent. And the terror of the Soviet Union shows, that the correction of wrong reforms is extremely difficult.

Nevertheless, during the fifties various western states have experimented with a mixed economy. Notably France deserves mentioning. Some branches are socialized, whereas for other branches a central plan is formulated. In Western Europe the plan is merely indicative, although the state policy aims to urge on the industries to conform to the plan. The results can not be called impressive. The intervention does not improve welfare, and not even the social well-being. Therefore many states have not even experimented with planning, and West-Germany is a typical European example of these sceptics1.

By then the social security is established, resulting in the welfare state or social state. A revolution would be nonsense. Indeed within the social-democracy many believe, that the original goals have already been realized. However, a movement, that is built for mobilizing discontent, can not simply integrate into the existing order. Therefore, now the social-democracy embraces Keynesianism, which also wants to centrally control the private industries, albeit merely at the macro-economic level. Notably the state must stabilize the volume of investments. Incidentally, Keynesianism is quite attractive for politicians, who like to redistribute money. The popularity of Keynesianism peaks during the sixties. However, also here the results are disappointing. This is partly caused by the irrational working-out, that especially the social-democracy presents for Keynesianism.

Thus, halfway the seventies the social-democracy is ideologically bankrupt. There is no longer a credible alternative for (neo)liberalism. Actually, an alternative is no longer needed, because due to the social safety net the liberal capitalism functions satisfactorily. This is painful for the social-democracy. In some states she still rules the state, but that is preceded by impossible and misleading promises to the electorat. During the eighties the social-democracy is a part of the social problems, and not of their solutions. More than ever she is in danger of becoming a collection of querulous individuals and unworldly fanatics. According as this becomes more apparent, the support for the social-democracy has waned.

Political movements commonly die after an ideological bankruptcy. The question is whether the social-democracy can still be saved. Adherents of the social-democracy point to the continuity in the ideological ideas. The social-democracy always tried to curb the power of private property. And she believes that the economy must be controlled by means of collective decisions, instead of by private initiatives. Due to the collective interventions the risks would diminish. On the other hand, the continuity of the social-democracy can be questioned. The socialization of property is truly different from central planning. One does not logically lead to the other. And Keynesianism is a policy at the macro level, which is not related to socialization or central planning. It are actually three separate ideologies.

However, traditions and institutions die hard. When people have found something to go by, such as an idea, then they stick to it. Conversely, spiritual leaders want to exploit the good reputation, that their movement has created previously. Due to the dynamic interaction between the top and the base, mass movements can become very rigid, and will not simply dissolve themselves. The social-democratic leaders naturally sense, that their reputation has become worn out. During the nineties they introduce a new ideology, the idea of the radical centre, which causes a revival of their movement. It must immediately be added, that the radical centre has little resemblance with the original social-democracy. Notably, henceforth the property rights and relations are accepted unconditionally2.

It is controversial, whether the ideology of the radical centre can be called the heir of the original social-democracy in all her diversity of socialization, central planning or Keynesianism. The present column wants to analyze claims concerning a possible congeniality of the radical centre with the social-democracy. It is obvious that the congeniality is not the ideological program, because in retrospect all social-democratic blueprints are unsound. The radical centre avoids blueprints. Therefore the possible continuity can be studied only in terms of values, on the moral-ethical level. This analysis can also clarify whether the radical centre is indeed different from liberalism or the christian-democracy.

The most general book about the radical centre, that until now has been studied by your columnist, is Third way reforms by the American J. Huo3. Huo uses the expression Third Way for the politics of the radical centre, because this is common in the Anglosaxon states. Henceforth, your columnist will continue using the expression

According to Huo the traditional social-democracy propagates the values of justice, fairness, solidarity and equality. After the mentioned ideological bankruptcy of the social-democracy, during the nineties of the last century the idea of the radical centre is developed. Two leading thinkers of the radical centre are the American A. Etzioni and the Englishman A. Giddens. Here it is already clear, that it is difficult to define the radical centre, because Etzioni propagates collectivism, whereas Giddens is an adherent of individualism. To be concrete, Etzioni belongs to the philosophical current of communitarism. Giddens is part of liberalisme.

According to communitarism, man is formed by the society, where he or she is formed and lives. There is pluralism. The individual obtains his norms and values from external sources. Since the individual is a product of his society, it is desirable that he behaves in a dutiful manner. He must be dedicated to his environment. On the other hand, in individualism the society is less important, because the values are universal. The individual can autonomously make his or her decisions, in a rational manner. Thus the politics of communitarism and of liberalism are mutually strained. The radical centre solves the tension between the individual and the collective by honouring them both4. This reminds of the model of the Dutch economist P. Frijters, where networks and groups have a symbiotic relation - although in the end Frijters is still an individualist.

Less than a year ago the Gazette presented the radical centre in a column about the ideas of Giddens. Then your columnist still complained, that a solution of the unemployment problem is missing. That is so far right, that the radical centre has reservations with regard to a demand side policy. That no longer works in the era of globalization. The states are obliged to balance their budgets, and thus engage in a supply side policy. However, the radical centre shows, that a supply side policy is also able to combat unemployment. For, the essential values of the radical centre are the productivity and the reciprocity. The radical centre wants to activate a maximal number of people, so that they participate in productive activities. And it provides the corresponding financial means.

The traditional social-democracy was strongly focused on the equality of incomes. She accepts the human passivity. However, the radical centre demands the equality of life chances. People must be enabled to unfold themselves. The seamy side is that now the equality of outcomes can not be guaranteed. People get what they deserve. However, they can rely on the state for the provision of resources, such as education, formation, and a temporary job with subsidized wages, if required. Incidentally, if desired the state can delegate the execution of the policy of activation to private organizations.

According to Huo the radical centre differs from neoliberalism, because it propagates reciprocity and solidarity (see p.20). The difference with the christian-democracy is less clear. Huo states, that the christian-democracy prefers a passive solidarity, such as the reduction of unemployment by means of early retirement of the workers (p.196). The radical centre is relatively willing to offer collective services, such as child care, training, and parent leave. These are arrangements, that are also supported by the middle class. Indeed the middle class is an important political target group of the radical centre. Nevertheless, the low-paid are also addressed. Therefore Huo calls the activation a prioritarian egalitarianism, to stress that especially the vulnerable groups can count on support by the state.

Huo acknowledges, that the political autonomy is severely restricted by the globalization, and by the technological progress. Nevertheless, Huo concludes that the radical centre does possess its own ideology. This ideology generates the energy, which allows to change the formal national institutions. Reforms usually require a collective action. In a two-party system this is fairly easy. However, in a system with coalition governments reforms are only possible, when a culture of corporatism is present. For, at the beginning the reforms are always accompanied by huge social costs, and then sufficient social support is vital. A disadvantage of corporatism is, that some trade unions engage in cliëntelism, and thus in exclusion.

Most of the contents in the book of Huo concerns an empirical study of the radical centre. He analyzes the social-democratic policy in no less than nine states, with seven of them in Europe. He presents time series of policy results, which suggest that the policy of the radical centre is effective. However, those time series are rarely longer than ten years, so that they do not give conclusive evidence for the long-term effects. And the social investments of the radical centre must prove themselves also in that period. Also, the method of Huo may be controversial. For instance, he categorizes both the Netherlands and France as continental systems, which are connected to the christian-democracy. However, the German Wolfgang Merkel makes a distinction between the Netherlands and France, as examples of respectively corporatism and state-capitalism5.

Another problem is that Huo has clearly become sympathetic with the social-democracy. This raises the question, whether he is always objective towards the facts, when he praises the radical centre. Your columnist believes that the radical centre is an interesting idea, but he is not yet convinced, that it is indeed better than other systems. Incidentally, it may be doubted that the radical centre is truly innovative. For, three quarters of a century ago, during the Great Depression, programs for activating workers were also common. It is not a coincidence, that in England New Labour gave its program the name New Deal, after the approach of the American president J.D. Roosevelt. In the Netherlands there were once programs for work provision. Their effect was rather meagre. It almost seems that they mainly aim to eliminate the social apathy, as a kind of European dream.

In Europe the English sociologist Anthony Giddens is the most important ideologist of the radical centre. A sketch of his views can not be omitted here, although it is already given in a previous column6. According to Giddens the traditional social-democracy does not have sound answers to the social problems. The people desire personal emancipation, and this can not be translated in a left-right controversy. Pluralism in society increases. Individualism creates a need for education, work and mobility (activation). Solidarity is interpreted as reciprocity, where rights are coupled to obligations or duties. That reciprocity is even expected in family life, for instance in child care and parent leave. Such an image of man requires a policy of the radical centre.

The citizens also demand from the state, that it is efficient. That is only possible, when the state relies more on the operation of markets. Decentralization can stimulate that, and moreover furthers the democracy. This frame needs a state, that cooperates with the civil society. Thus the state withdraws from the policy execution. The spirit of enterprise is encouraged, but the state guarantees, that the risks remain bearable. In such a society the equality consists mainly of participation and inclusion. Giddens calls this social liberalism. Work is essential, because it makes people truly independent and autonomous. On the other hand, passive income provisions incite love of ease. Active measures are an investment in human capital. They can be a wage subsidy, but also incitations such as exemptions from taxes, especially for the low-paid.

Some critics reproach Giddens, that his expectations with regard to the operation of markets are too high. Giddens replies, that he actually advocates the regulation of markets. For, these can curb the power in markets, for instance those of monopolies. However, it is also necessary to remain vigilant against the suffocating state bureaucracy, which degenerates into rigidity and authoritarian behaviour. Efficiency is a common interest. Indeed the traditional social-democracy has erred here (see p.57 in The third way and its critics). The radical centre furthers the democracy, because it satisfies the needs of the middle class. It is the bearer of the knowledge economy. This can be reconciled with a policy for the poor. For, sometimes talent benefits from support. A society of trusting networks is a productive capital7.

It it true that Giddens influences the social-democracy, but yet New Labour under Blair chose its own course. A good analysis can be found in the book by S. Driver and L. Martell, which indeed has been consulted for this paragraph8. The authors believe, that the policy of New Labour is a mix of liberalism and social-democracy. The latter affiliation becomes apparent notably in the active role of the state, and in the investments in public services. Liberalism can be observed in the preference for the operation of markets. Therefore New Labour is a hybrid movement, which is internally pluralistic. Considering the history of New Labour this does not surprise. At the start of the eighties in the last century Labour still believed that the policy of Thatcher should be combatted with a shift to the left, so that it became even more extreme than at the time the Dutch PvdA. Then the return to reality is a long process9.

Around 1990 Labour still wants to conform to the continental social-democracy. However, they change their minds because of the economical problems of Japan and Germany. Henceforth the American New Democrats under Clinton become an example worthy of imitation. New Labour is born in 1994, when Blair is chosen as party leader. Almost twenty years of Conservative hegemony have changed the English society forever. This makes New Labour more liberal than its sister parties on the continent. It reduces the protection against dismissals, and lowers the benefits. The society remains rather unequal. The primary goal of New Labour is inclusion, by means of jobs. Therefore New Labour invests in education, in child care, and in health care. This is a clear rupture with the course of the Conservatives. However, the means for these services must be earned by economic growth.

New Labour purposefully seeks the electoral support of the lower middle class. The spirit of enterprise is encouraged and the civil society is stimulated10. Notably Blair sympathizes with communitarism. He advocates collective morals, which bind the citizens. Welfare must be realized by means of employment, as well as the battle against poverty. Anti-social behaviour is opposed. The trade unions are not the natural allies, and must prove that they can act responsibly. New Labour prefers a supply-side policy, and this includes moderate wages. It has already been remarked, that the labour laws are made more flexible. On the other hand, the Social Charter of the European Union is ratified.

The performance of the public services must be improved. Therefore New Labour maintains the new public management, which advocates performance management by means of indicators and goals. In some branches quasi-markets are introduced, where cooperation remains a possibility. Moreover, Blair propagates more freedom of choice, due to a diversified offer, for instance in education (see p.132). Finally, it is interesting, that the preference for decentralization has led to more self-government in Wales and Scotland. On the other hand, Blair wants to control the New Deal by himself, and manages it without a say of the municipalities. All in all Driver and Martell conclude that New Labour does not have a clear ideology of its own (see p.53, p.168). Policy is formed by an internal compromise.

Huo presents in Third way reforms an empirical analysis of the English policy. Summarizing, during the rule of the government Thatcher the rights of the trade union movement have been curtailed significantly. Thus the unions do not inhibit the reforms of New Labour. And jobs have already been made flexible. The government of New Labour initiates the New Deal program, which tries to direct the unemployed to jobs. It is executed by Jobcentre Plus. The policy mainly adresses the youth and the persistently unemployed. The unemployment is reduced, albeit sometimes by means of worsening terms of employment. The trade union movement is willing to moderate wages. Nowadays many terms of employment are determined by law, so not by means of collective bargaining.

The low-paid obtain extra incitations to work by means of tax exemptions (Making work pay). The benefits and support are partly paid out as fiscal means. The child care is facilitated, and the child poverty is opposed. Thus the American minimalism is circumvented.

After the Second Worldwar, for twenty years the German social-democracy (the SPD) was pushed into the role of opposition at the federal level. It has profited from this period by carrying through a programmatic reform into a pragmatic party. In 1959 the SPD adopted the program of Godesberg, which by the then standards may be called liberal. During the seventies the SPD appoints the recently deceased Helmut Schmidt as chancellor, who is universally respected and trusted. Thus during the nineties the SPD feels less need to reform ideologically than Labour. The German debate aims at continuity, and therefore the ideology of the radical centre is adopted with reluctance. A recent German party-ideologist is the policy scientist Thomas Meyer, and his view will be consulted here for illustrating the present ideas within the SPD11.

According to Meyer the core values of the social-democracy are freedom, fairness (justice), and solidarity. Nowadays these values must be realized within the boundaries set by globalization, the knowledge economy, austerity and flexibility. The social-democracy differs from liberalism by the desire to guarantee a decent existence for all, by offering opportunities for participation, and by a certain solidarity. Individuals are responsible for themselves, but the society secures their existence. For, the security of existence is a natural condition for participating. Besides, the society must continuously offer opportunities, for instance by organizing retraining. It is precisely this reciprocity, that dictates obligations to the individual, because the system must be maintained. Everybody contributes to solidarity by doing productive activities, and by minimizing the use of social benefits.

Meyer accepts unequality in incomes and wealth. The reward for performance is an indispensable incentive. He states that the radical centre of chancellor Gerhard Schröder (in German Neue Mitte) is not yet sufficiently concrete. Meyer believes, that tasks must be transferred from the state to the civil society. The stimulus of communitarism can make state interventions superfluous. Public services must further autonomy and choice. Nevertheless, Meyer wants more than just social inclusion. Activation can not replace the duty of the state to create employment. Meyer even rejects the recommendation of the spirit of enterprise12. He wants to replace this by the call for social responsibility. Here it appears that Meyer does not fully support the demand of Giddens, that citizens must become independent by means of productive jobs.

After 2003 the SPD breaks up as a consequence of her choice for the radical centre. just like once the Dutch PvdA and the English Labour Party broke up as a consequence of left-wing extremism. During the election of 1998 Schröder presents the SPD as a reform party, because the German economy stagnated and must be modernized. The reform of the social security by the Rot-Grün coalition under Schröder causes so much resentment in the trade union faction of the SPD, that those members form the pression group WASG. Later the WASG will merge in the new party Die Linke, where also the former SPD leader Oskar Lafontaine starts a second career.

Originally Schröder hopes that the reforms can be realized by means of tripartite consultations, and he tries to reinforce the German corporatism. The success of the Purple "poldermodel" inspires him, and he attempts to establish an alliance of labour (Bundnis der Arbeit). A core target of Rot-Grün is the reduction of the additional costs of labour, especially for the low-paid. After several years the coalition concludes, that the industries (including the trade unions) are not able to modernize the social security on the basis of consensus. Then Rot-Grün decides to realize the reforms in a top-down manner. Therefore several committees of political and scientific experts are formed, so that the proposals will yet have sufficient social support. The package of reforms is called the Agenda 2010.

Schröder feels mainly responsible towards the people, and these want a prospering economy. Political leaders always search for majorities. Therefore he uses the slogan "first the federation, then the party" (see p.85 in Klare Worte, and again on p.162 en 233! 14). Unlike Thomas Meyer, Schröder does believe that the spirit of enterprise is important. Germany needs a performance-based elite (p.122). The human dignity requires independency, and this is realized by jobs. There is no right of supported laziness (p.82). In a previous column Schröder states, that the social security must be a trampoline. There it is already clear, that Schröder promotes an activating state, flexibility of the labour market, and part-time work. The youth must learn to be independent and willing to undertake. Schröder even refers to the legitimate right of investors to have some security. They also serve their society!

Huo presents in Third way reforms an empirical analysis of the German policy. Summarizing, Germany is the typical example of an insider / outsider society, because notably the industry trade union IG Metall is very powerful. Germany is still quite industrial. Therefore that union can guarantee rights in her collective agreements, such as early retirement, that are not accessible for the unorganized. The social partners try to shift their own costs towards the state. Rot-Grün is not able to prevent this. Rot-Grün does start immediately with activating the youth on the labour market. Later the Hartz reforms are realized. Henceforth the duration of the normal unemployment benefit is merely a year. All benefits are controlled by the Job Center, which activates with a mix of incentives and punishments. The local advisor determines the means of activation, that are made available.

The tax wedge in the wage costs is reduced. However, the trade union movement blocks wage subsidies. It also rejects increasing the flexibility of labour. Furthermore, Rot-Grün has reformed the pension system, by adding a private component. In the period, analyzed by Huo, the Agenda 2010 has not yet affected the unemployment. Nowadays the model is praized, since Germany has withstood the financial crisis in 2008 in an excellent manner. Nevertheless, the dual social security naturally remains a problem. Workers in the German industry have more rights than workers in the lowly-paid services. Even the federation DGB can not change this situation. Incidentally, the organizations of employers also accept this exclusion.

The preceding paragraphs attempt to sketch a somewhat coherent picture of the radical centre, at least of its implementations in England and in Germany. It has been remarked at several places, that the radical centre is a pluralistic movement. It is not purely liberal. This allows it to prosper both in the Anglosaxon system of England and in the continental system of Germany. The volumes Sicherheit im Wandel and The global third way debate illustrate some aspects of this ideological pluralism. Thus for instance the traditional social-democrat Müntefering yet concludes, that it is change that maintains security (SiW p.6). The political scientist Herfried Münkler states, that long-lasting benefits degenerate into charity and paternalism. Since benefits foster dependency, they must last as short as possible (SiW p.38). The decentralization of the social security strenghtens the social control (p.45).

The pollster Richard Hilmer concludes, that in 1998 the SPD could win the elections thanks to a growing support from the middle class (p.101). Thus Rot-Grün unites the middle class and the lowly educated. However, the latter group is in danger of becoming demoralized and of abstaining from voting. Within the SPD the zest for a Keynesian stimulation diminishes, and it was never large anyway. The minister of state S. Mosdorf states, that the national debt is a lack of solidarity with future generations (SiW p.142). When the state borrows less, then the industries dispose of more capital for investments. It is already clear from the preceding paragraphs, that the SPD is also critical towards the trade union movement. The former trade union official K. Blessing states on p.158 and further, that knowledge workers want to defend their own interests. They prefer the dialogue, in stead of agitation. Therefore the trade unions must lessen their hierarchical structure.

The political scientist Wolfgang Merkel stresses once more, that social justice must be reconciled with economic efficiency (Tgtwd p.57). He criticizes the enormous disability for work in the Netherlands (Tgtwd p.65). According to the American policy scientists W.A. Galston and E.C. Kamarck the higher middle class expands (Tgtwd p.102). They leave the wider middle class, which therefore shrinks. Thus the income distribution becomes more unequal. This is partly due to the many wired workers, who operate the automatic systems. On the other hand, the well-known sociologist Esping-Andersen believes, that lowly paid jobs in the service sector are indispensable for the creation of employment (p.136). They offer opportunities to the youth and to the lowly educated. Fortunately the demand for such services increases thanks to the young families and the old people. In fact the house-keeping integrates into the formal economy!

Note that education does not help to raise the wage of the workers. The demand is simply insufficiently strong. The only way to raise the wages is subsidy. Furthermore, Esping-Andersen believes that the demotion of older workers is desirable, and it is actually done in North-America. This combats the efficiency wage, which makes the jobs of older workers unnecessarily expensive. The policy scientists M. Ferrera, A. Hemerijck and M. Rhodes state, that activation contributes to the reduction of long-term unemployment, and thus maintains the productivity. Namely, during long-term inactivity the individual skills are not updated. In this respect human capital is similar to capital goods (Tgtwd p.124). Thus flexwork is better than no work. A worker may be temporarily poor, as long as it is not permanent.

Incidentally, these three scientists advocate some principle of beneficiary in social security, because this enhances its efficiency (Tgtwd p.119). For instance, consider old people, who at the moment are relatively wealthy. According to the sociologists L. Leisering and S. Leibfried, nowadays the social assistance is not merely used by atypical citizens. Therefore it makes sense to integrate the assistance with the benefits for unemployment (p.206). The historian S. Szreter recommends an expansion of the civil society, where however the state must create guarantees for vulnerable groups (p.291). The radical centre wants to accumulate more social capital. According to the law-student H. Collins the radical centre wants to transform the relation between the enterprise and its workers into a flexible partnership (p.304). Then the trade unions are mainly facilitating.

The famous economist J. Stiglitz points out, that economic growth remains essential for increasing the social capital (Tgtwd p.343). The radical centre wants a state, that supervises the optimal functioning of markets. Incentives are important. The state must expose its own agencies to competing markets. Doctrines are useless! Stiglitz also discusses the global institutions. However, the radical centre is a western find, which can not simply be exported. Incidentally, in the radical centre there is disagreement about the global policy. According to the Brazilian L.C. Bresser-Pereira the radical centre is neither cosmopolitan, nor nationalistic (p.365). On the other hand, the Englishmen D. Held (p.394) and A. Giddens do demand a cosmopolitan rule. Here the intellectual character of the radical centre leads to futuristic fantasies15. That is regrettable, because they undermine the credibility of the radical centre.

At the start of the eighties the Netherlands had become economically and socially disrupted. Henceforth the Netherlands has been reorganized by the three cabinets Lubbers, with the christian democracy in a pivotal position16. Their policies are continued, and somewhat improved, by the two Purple cabinets under Wim Kok. The liberal policy of Purple was quite successful, although there was also severe criticism by the movement around Pim Fortuyn17. Huo identifies in his book the PvdA with Purple, but actually this party was a minority within the cabinet, and the VVD was even almost as big. Therefore it is interesting to see which parties will eventually claim the heritage of Purple. The PvdA can indeed claim it, but the traditional social-democratic current within the party shows little enthusiasm.

The history of the social-democracy is a sequence of ideological errors. It is difficult, starting from a faulty social perspective, to develop a new ideology or paradigm, that can compete with other, more stable movements, such as liberalism and conservatism. In the absence of a sound foundation the result of the modernization of the social-democracy is uncertain18. Precisely because the social-democracy is continuously forced to change its paradigm, she has the dubious tendency to relapse in the just abandoned ideologies. For, the new find originates commonly from the party top. The members are formed and versed in the abandoned paradigm, so that their flexibility for changing their course is limited. Under normal circumstances the party modernizes internally by the influx of new members. Therefore the ideological rigidity becomes more severe, according as the group of party members is more aged, like in the present.

Moreover, the absence of a sound ideology makes it tempting to base the program on clientelism. But group interests can conflict with the social cohesion and with the general interest, or in scientific terms, with the social capital. In the end everybody is worse off with clientelism, but especially the groups without a lobby or pressure group of their own. It has just been stated, that therefore chancellor Schröder sometimes had to serve his country and not his party. The PvdA has built on the experiences with Purple for the formulation of a new Manifest of Principles. There the mentioned ideals are freedom, democracy, justice, durability and solidarity. They mirror the international social-democracy, and are in agreement with the views of Thomas Meyer and Jingjing Huo.

Later the PvdA orders her scientific bureau WBS to elaborate the core values19. In a previous column, dating from 2013, the result of this Van waarde project has already been described. In her book with the same title WBS director Monika Sie Dhian Ho mentions as the core values of the social-democracy the existential security, decent work, emancipation and bonding20. The just mentioned core values differ in their tone with the ideals of the Manifest of Principles. It is worth pondering over this fact, notably in this column, which is dedicated to the radical centre. For, the radical centre advocates a renaissance of freedom, and the question is how the four core values of Sie Dhian Ho bring this about.

The ideal of freedom demands a negative right, in the sense that it wants to protect the citizens against the dictature of the collective. However, the four core values mainly concern insurances, so positive rights, which necessarily will be realized at the expense of others. Thus decent work is a typical demand of the trade unions, which easily can lead to the exclusion of non-organized workers (the insider / outsider problem). Secondly, the core value of emancipation includes the passive variant of paternalism, although she can also be interpreted as a personal duty. It would be unrealistic to expect that the social-democracy emancipates people. On the contrary, the people must support and shape the social-democracy. Due to this double interpretation your columnist believes that the call for emancipation is rather cheap.

A third point of reflection is that the need for productivity can not naturally be derived from the four core values. Nevertheless, productivity and efficiency are a general interest. Many, especially in the middle class, have ambitions and want more than merely an existential security. Therefore care must be taken that decent work will not hurt the consumer. In other words, an ideology is only defensible, as long as she offers welfare. That is certainly in the original social-democracy always an important claim. The radical centre revives this demand.

These notes are not meant to be a rejection of the four core values from the Van waarde project. They do illustrate, that some difficulties exist. In any case the negative right of freedom must be stressed, because the social-democracy wants to combat the existing order, and then sometimes tends to use repression. Thus she must clearly promise to respect freedom. Therefore your columnist is not naturally willing to exchange the ideals of the Manifest of Principles for the four core values21.