Figure 1: consumers cooperation

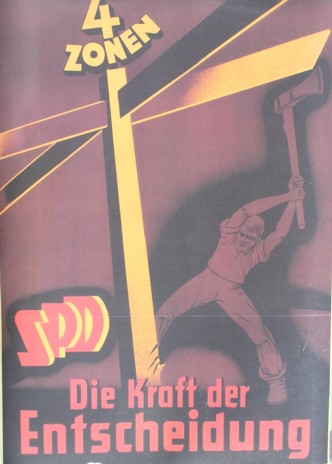

In the past decades the central planning of the economy has become suspect. That was not always the case. Originally the social-democracy has pleaded in favour of collective property. Here the German SPD has done pioneering work. Already in 1891 the programme of Erfurt wanted to nationalize notably the oligopolies. However, three quarters of a century later, in the programme of Bad Godesberg (1959), the SPD preferred a surprising new ideological orientation. The doctrine of nationalization was relaxed, and in fact abandoned. This raises the question, why the political preference had changed. The question is especially pressing, because nationalizations seem to be economic improvements. The present column sums up some of the facts.

The information in this column about the ideas in the SPD is taken notably from the books of the social-democrats R. Löwenthal, D. Klink and H. Deist1. The books of Klink and Deist date from the Godesberg period (1959), and therefore have a different perspective than Löwenthal. Valuable background information about the plan-ideology until the Second Worldwar has been obtained from the book of the Dutch economist Ed. van Cleeff2. Van Cleeff is a traditional christian democrat. Especially the historical induction in the first part of his book is relevant for the present column.

In Europe the twentieth century has seen a revival of the intervening state. Of course the idea of the central planning has historical roots, that go back a long way. Her origin can be attributed to the socialists, who thus want to end the chaos and exploitation on the capitalist market. Nationalizations form a common part of these ideas. This column wants to analyse how political aspects influenced the debate about the planned economy.

The nature of the analysis is complex. For simultaneously with this development the democratic state has gained terrain, at least in Europe. This introduction of democracy met resistance, notably from the Jacobin movements, which try to establish a political dictature. Thus there was a double struggle: the one for the active state, and the one for the democracy. Jacobin groups agitated both within the liberals and the socialists. Against the England of Attlee there is the Soviet Union of Lenin. And against the America of Kennedy there is the Chile of Pinochet.

Therefore it is difficult to estimate whether the historical experiences require a political explanation, or an economic one. Especially in a political analysis a subjective interpretation is unavoidable. Here the development of the social-democratic discourse will be outlined broadly. That is to say, the starting point is, that the idea of economic interventions by the active state can be traced back to the social-democracy. Notably the ideas of the German social-democracy are followed, as represented by the SPD, because they were leading for the early theories about planning.

Incidentally in the modern social-democratic circles itself the ideas of nationalization and planning are controversial. The French social-democracy has been most loyal to the original ideas. In general the French ideologists state that these ideas have been questioned first at the SPD Congress of 1959 in Bad Godesberg. There a programme was approved, which has social liberal characteristics3. The logical question is why the SPD has made such a rigourous turn. Are the planning and the nationalization of enterprises indeed outdated for technical and cultural reasons? The present column will study the development, both from an economic and political-historical perspective.

First the theory: the common economic literature rejects the planned economy for three reasons4: first, in the planned economy the supply is too one-sided. The consumer has little choice from various types. Incidentally this has an advantage. Namely, thus cost-savings can be realized in the mass production. Second, the central planning agency can not process all information, which is needed in order to make sound decisions. And third, the plan will be sabotaged by the lower executing agencies in the hierarchy.

The conclusiveness of these objections looks not very impressive. What is the principal difference between the information management of a public planning agency and a transnational enterprise? In cases where the acquisition of information fails, decentralization is possible. Sabotage of targets will undoubtedy occur. That is a part of human nature, and has its merits. But why would large private organizations suffer less from this?

More interesting are the conclusions of the Leninist economist Eva Müller, who was a leading official in the East-German planning organization. She criticizes mainly the lack of flexibility in the planned economy. The production system has insufficient mechanisms for adaptation, so that excesses and shortages can not be eliminated. Especially the process- and product-innovations derail the total production, because their consequences are difficult to foresee. Therefore the planning agencies are inclined to avoid those innovations.

Indeed a planned economy is risk-averse. Also the West-German economist Wagener calls this her greatest weakness5. Entrepreneurs have difficulty in forcing through their initiatives, because they are thwarted by the planning agencies. When the planned economy has open borders, then the entrepreneurs will leave and settle down in states with more economic freedom. Yet also the experiences of Müller are not the definite refutation of economic planning. The mentioned rigidity is to a large extent caused by the dogmatic Leninist system, which suppresses all deviating ideas, because it sees them as an existential threat. In the following paragraphs the importance of the spirit of enterprise will be studied in more detail.

Next the question arises how the political perspective on the nationalizations has developed. This has a long history, which can be divided in roughly four phases. The story starts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century: then the society is morally and practically bankrupt, because the late-feudal or absolute rule does no longer meet the demands. In that period the socio-political system has also become petrified and outdated. The situation is unbearable to such an extent, that revolutions are the best solution for a change of power. In this way the bourgeoisie succeeds in claiming her political place in the system. She pleads in favour of an extreme liberalism. But the proletariat, the labour class, remains in a subdued position. Therefore the proletariat is forced to develop its own revolutionary ideal.

The intensification of the division of labour in the eighteenth is followed in the nineteenth century by an enormous concentration of activity. The accumulation of capital perseveres, and leads to the establishment of the large-scale industry. New forms of property emerge, such as the stock company. The liberal economy develops inhumane characteristics and defends the laissez faire, laissez aller ideology. The most repulsive form of this system is indeed the Manchester capitalism. The entrepreneurs turn out to abandon all social or cooperative feelings. The ethical leaders start to realize, that this capitalism does not have a future.

The already existing idea of the collective property nestles in wide layers of the population, but evidently mainly in the proletariat. Nationalizations are a socialization of the production. Thus the exploitation of the workers could be prevented. The democracy must not be restricted to politics, but she must incorporate the economy. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels provide the social-democracy with a political-economical analysis. According to them the proletariat will constantly grow in size, and moreover it will impoverish. This recipe, the formation of a large majority of dissatisfied people, guarantees that the social-democracy will be victorious6.

In the programme of Erfurt (1891) the SPD indeed makes the political demand of the nationalization. Klink notices, that the nationalizations do more than merely end the economic exploitation. Namely, they also eliminate the social class structure, and thus soften the social conflicts. The programme of Erfurt demands for economic planning in order to bridle the conjuncture7.

Indeed in practice the social-democracy gains a remarkable political support, as the most motivated protagonist of the interests of the workers. She establishes organizations, which make preparations for a rapid change of power and the expropriation of private capital. The speakers of the workers are ideologically formed in order to be able to take conscious political actions. The trade unions start to grow impetuously. Incidentally, there are not merely social-democratic unions, but christian ones as well. It is not a coincidence, that in this period of purposive organization the anarchist ideology decays.

It is also the period of the establishment of various insurance companies for covering the unemployment and illness. Besides many social-democratic publishers and newspapers are formed. This economic activity strenghtens the conviction, that workers can be managers in an alternative economic system. There are lively experiments with the forming of workers cooperatives. Sometimes they are viable, notably when they must compete with the small industries. But it turns out, that they do not really have a competitive advantage. It becomes clear, that social-democratic enterprises must also be efficient. The social-democracy starts to appreciate the small industries.

Moreover the knowledge of the production techniques and organization (scientific management) increases to such an extent, that the workers collectives can no longer be entrusted with it. The company hierarchy with a central command becomes indispensable8. In the era of the colonialism the global empires collide, in their search for new markets. The social-democracy shifts from a criticism on private enterprise in the general sense to a criticism on the power concentrations of the oligopolies. The high finance becomes the new enemy9.

The social-democracy acknowledges the necessity of the concentration and the increased scales. They yield a more effective production. Therefore the social-democracy does not object to the formation of trusts and cartels. In this respect she differs from the liberalism. The evil houses in the abuse of power, which expresses itself by price manipulations and by the exploitation of other branches (by shifting costs to them). Therefore in the really monopolized branches the state must take over the management of the enterprises. Only the state can take into account the general interest in the management10.

At the same time the social-democracy revises her expectations of the future, thanks to the efforts of the revisionist Bernstein. She concludes that the size of the proletariat stabilizes, and that it shares in the growing wealth. She realizes, that the political victory is not an automatism11. In 1914 the European social-democracy experiences a severe set-back. Her own adherents, the proletariat, abolish the rebellion against the warmongers, and is carried away by the nationalist sentiments.

The end of the war in 1918 creates favourable conditions for the revolution, certainly in the overcome states. There the social-democracy establishes administrative institutions, the so-called labour councils, which already in 1905 were a large success in Russia. Yet it turns out that the social-democracy is still not popular and powerful enough for the revolutionary coup d'etat. Even the introduction of the representative democracy in 1919 does not enable her parties to obtain the majority. The middle class and the peasantry dislike the nationalization of property.

The revolutionary chances decrease rapidly. As a consequence of this disillusion the social-democratic leaders start to doubt their own ideology of the collapsing capitalism. Henceforth the class struggle is explained as a process of emancipation and awakening. The instrument of the revolution is definitively abolished, because thanks to the new democratic rights the will of the people can be expressed in a peaceful manner. This implies a silent rupture with the popular movement, because the parlementary group transforms from a mouthpiece into a political mediator12.

In Russia the Leninists, a group of Jacobin socialists, conquer already in 1917 the power by means of force, with the help of the farm workers. The party establishes a dictature, and introduces a planned economy, partly perforce due to the (civil) wars. The state has as its future aim the complete nationalization. The apparent success of the Leninists creates a split in the labour movement. Many Leninist secessions emerge in the social-democracy. The social-democratic parties and the new Leninist parties become mutually alienated, especially when outside the Soviet Union the latter ones degenerate into marionettes. The fascination for the economic experiment is overshadowed by the horror of the political terror.

In the western states the social-democracy experiences even in her parliamentary efforts more resistance than had been expected. She can not mobilize sufficient political support for the complete nationalization of the large-scale industry, or even of separate branches13. It is clear that the bourgeoisie offers a vigorous resistance. And the proletariat demands for more wealth, but not necessarily for socializations and nationalizations. That is a problem for the social-democracy, which has the ambition to conquer the political rule.

In an attempt to offer still a credible political alternative the stand is taken, that planning is possible without nationalizations. Henceforth the social-democracy preaches up the intent to break the monopoly power and democratize the state. Also the establishment of the workers councils (in the German language: Betriebs-rat) reduces the need for nationalizations, because they allow to resist exploitation in their own way14.

Van Cleeff points out, that the idea of an economical order becomes popular in the period 1914-1932. The order implies the formation of bodies and agencies, which coordinate the economical actions. Van Cleeff presents in his book a detailed description of the various national planning system15. The socialist propaganda and the social-democratic successes of the past decades have contributed to a growing acceptance of the planning approach. In various European states the ideological climate is favourable to such an extent, that the state takes indeed up the control of the economy. In Italy and later in Germany fascist regimes establish corporative structures. In the papal encyclical letters (mainly Quadragesimo Anno) the corporatism is recommended. Also the New Deal policy of the North-American president Roosevelt has been called a form of planning.

The social-democracy still believes, that the regular economical crises will enhance her electorat (notably the working class). In 1929 a crushing depression begins16. But against the marxist expectations the voters move to the extremist parties (fascists and Leninists) instead of to the social-democracy17. In the fascism the planning is controled by the monopoly capital and by the state bureaucracy. The social-democracy must observe how the tightly planned economy creates discomfort and alienation. Large groups of people feel restricted in their personal freedom. In democratic states a strong resistance against nationalizations remains present. That undermines the social-democratic argument of the freedom by planning.

After the Second World War the political climate for the social-democratic political alternative is very favourable. The planned economies of the Leninism and of the fascism have made impressive war achievements. The other states have also established many planning agencies during the war. In England a socialist government starts profound reforms. Scandinavia and New Zealand also get socialist governments18. The national economies become intertwined, and supra-national organizations are founded. Henceforth the planning must occur at the continental level. That restricts the opportunities for social-democratic parties, who are organized at the national level. In the beginning some people hope that a European socialist order will soon be realized19.

The social mobility improves, so that the tensions diminish. The management becomes separated from the capital. Since the power shifts from the stockholders to the management class, the nationalization makes less sense. The social-democracy wants to get round the new management class. That class itself is not social-democratic, but she is open to democratic decision procedures, and thus controlable20. In 1946 Löwenthal (and the SPD as well) still wants to buy all private monopolies and pay by means of government stocks. But he would prefer to break the monopoly power without nationalizations. He proposes a central plan, which broadly outlines the investments and the income distribution.

The party congress (Partei-tag) in Hannover (1946) wants to begin with the nationalization of the winning of raw materials, because this plays a strategic role. Moreover, those branches have the character of monopolies, and they are crucial for the economic planning. Here the nationalization means the transfer into public property (which apparently is not equal to state property)21. An advantage of planning by social-democrats is the full employment. Also Löwenthal believes that it is possible to control the conjuncture. It is remarkable that he does not fear the rise of the bureaucracy, and apparently wants to transform the monopolies into state enterprises22. A decade later Deist will make a more negative judgement - although the situation has not profoundly changed.

Unfortunately the German social-democracy experiences the negative after-effects of twelve years of repression and persecution. Besides the SPD leaders have become distrustful of their own people. The people's will turns out to take on grotesque forms. And several aspects of the particular German after-war conditions are unfavourable for the SPD. First, the occupation of Germany by the victors harms the social-democracy, because she furthers nationalism. This unites the people, whereas the social-democracy has the mission to put the conflicts of interest on the order paper.

Furthermore, the armies of occupation did not really sympathize with the social-democratic programme of nationalization. The Allied Powers block various attempts of the federal states under a social-democratic government to realize their programmes. At least as troublesome is the emergence of the Cold War. It forces the social-democracy to take oppose firmly to the Leninists, more than is justified by the ideological differences. The debate polarizes23. In the background the grave conflict between the FRG and the GDR will have played a role, because West-Germany needed the support of the American army.

The only remaining planned economy, in Leninist Russia, performs reasonably well, and sometimes realizes outstanding achievements, notably in space travel. But in general the planning does not exhibit the advantages, which originally had been expected by the social-democrats. The broad enthusiasm for planning in the thirties fades away24. It turns out that the workers are hardly better off in the new Leninist planned economies. A striking example: in East-Germany the labour-norms are puffed up in an obligatory manner, which in fact amounts to a declining salary. In the clashes during the strikes from June 17, 1953 dozens of people are killed, including a handful of police officers. The Leninist planned economies suffer from a massive emigration of citizens, mainly the well-educated ones, to the capitalist market economies25.

In the post-war years Europe experiences an unprecedented economic growth. There is full employment and the workers see the wellfare rise by leaps and bounds. Besides the increased vertical mobility guarantees chances for a successful carreer to everyone. This makes the task of the social-democracy more difficult, because the people see less reason for economic reforms26. At the end of the fifties the political leaders of the German social-democracy are fed up with their role in the opposition. Moreover, a new generation of politicians has emerged, which is less sensitive for the ideology. She finally wants to rise to power. In order to reach this goal a programme is designed and approved, which has clear social-liberal characteristics: the programme of Godesberg.

So the programme of Godesberg is actually a bid for power, which also challenges the dominating German christian-democracy. It is significant, that merely the energy branch (including the unprofitable coalpits) is marked for nationalization. This is partly motivated by the protection of employment27. The programme is not enthusiastic about the Keynesian stimulation of the economy. It tries to get closer to the social liberalism of the economic School of Freiburg (Walter Eucken). Besides the social-democratic demand for democracy in the economy, it is stated that people must keep their economic freedom28.

Deist, who has drafted the economic paragraphs in the programme of Godesberg, is an adherent of private property, also in the oligopolies. Here he does want to limit the property rights, in those cases where actions are irresponsible. In particular he believes in competitive markets. He is convinced, that the consumers will benefit by them. Therefore it is the task of the state to curb the market power. According to Deist nationalizations are merely useful in stagnant branches, where the private production fails29. The management of the nationalized enterprises must be handed over to mixed councils, with representatives of the executive, the workers and independent experts. The council replaces the shareholder assembly. Deist states that they must be democratic bodies with self-government, and he rejects the direct control by the state30.

Seen from an economic-scientific point of view the policy change is not necessary. There is no objective reason to give up the nationalizations and the planned economy. It is a political-opportunist choice of the SPD, which had suffered from ideological dislocation and political set-backs. As such the programme can not be understood as a spiritual liberation, but it is more a dictate due to the unfortunate circumstances. In 1962 the SPD abandons even the nationalization of the energy branch. According to Deist it no longer plays a crucial role31. Klink states, that henceforth the SPD must propagate a social-ethical programme. Indeed in 1966 the SPD can finally form a "Great Coalition" with the CDU, thanks to the new course. But at the international level the German social-democracy moves into an isolated position.

For instance the English Labour Party maintains the original course, at least until the emergence of the Third Way movement in 1997. Still in 1982 the French Socialist Party of Mitterrand gets in power and subsequently forces through the original course. Complete branches of the big industries are nationalized, and they will remain so for many years32. Interesting are also the successes of the Asian states (South-Corea, perhaps Japan) with corporate systems. In the Netherlands the privatizations, which have been carried through by a (partly) social-democratic government, are unpopular with the people. The workers of the state-owned enterprises have tried to resist the privatizations. The discord is so large, that in fact the Dutch social-democracy is split in two parties.

The table 1 presents some connections, which have been discussed in the preceding text.

| period of awakening | period of buildup | revisionist period | conformist period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| order | associations of workers | state-owned enterprises and cooperations | industry policy | incidental branch policy |

| interventions | networks | central planning | central management | correcting interventions |

| role of the state | minimal state (Marx) | state leads | state defines the framework | state is a player |

| programme | Communist Manifesto (1848) | Programme of Erfurt (1891) | Programme of Heidelberg (1925) | Programme of Godesberg (1959) |

The now following list highlights once again the advantages and disadvantages of nationalization and central planning. Advantages are:

So nationalization certainly has attractive sides. Thus the realization of a planned economy remains also in the future when of the most fascinating human challenges. Perhaps nationalizations can redeem the promise of more welfare. This is worth stating. This column shows the opportunist behaviour of politicians in reaction to the actual developments. The propagated ideology turns out to aim at a rapid increase of the electoral support, while the chances to really improve the welfare and well-being play a subordinate and instrumental role. In politics there is no room for economic perspectives, which in the short run do not yield a democratic majority. This holds even, when they are objectively superior.

A political party is obviously not a forum for economists. A political leader wants to rule33. But it would be desirable to have politicians, who protest when the socially common ideology paints a one-sided picture of reality. When parties censure themselves, because they want to rule, then there is no political alternative and thus also no chance for innovation. In times of neoliberalism the states are forced to abandon planning and nationalization. The international institutions such as the World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund try to isolate the economies of rebellious states. Nevertheless it is not surprising, that planning and nationalization continue to pop up. Always there is some state somewhere in the world, which tries his luck in this way. The advantages can be impressive.