Figure 1: Gerhard Schröder

During the preceding months two columns about the social-democratic views on the general interest have appeared. They allow the social-democracy to translate the collective well-being into a political target- or policy-function. However, in the course of time this view has changed considerably, The present column describes the views of six leaders from the most recent decades, namely Hans van den Doel, Helmut Schmidt, François Mitterrand, Paul Kalma, Femke Halsema, and Gerhard Schröder. They clearly illustrate the rise of the Third way ideology.

The core problem of the political economy is the transformation of the individual needs of the citizens into a general interest. It is clear that for such a transformation an instrument is required, namely the state. However, the character of the state is controversial. Of old the attention focuses on the nation-state, that organizes the administration of a rather homogeneous nation, with its own language and tradition. In that case the state is mainly the bearer of shared ethics or morals, that give the community her identity. The administration is central. However, at present some prefer to define the state as an administrative body, that is established by networks of entrepreneurs and intellectuals, in order to maintain some order in the markets and in society. In that view the state must mainly provide a judicial system, that mediates in conflicts of interest. Incidentally, no collective morals are imposed on the citizens. The administration is fairly decentral.

Suppose that the desires, needs and interests of the individual citizens are represented by a general welfare function W. Furthermore, suppose that the state is democratic, so that the people themselves form the sovereign power. Then the popular representatives install a government, that gets the instruction to optimally further the wel-being of the people. The government develops a policy, that serves the universal or general interest, and that can be represented by a target function U. Now the policy formulation and execution can be represented by a symbolic process W → U. Five obvious questions arise, which incidentally are interwoven.

In the present column the philosophical ideas with regard to these questions will be studied for various political scientists and writers, and notably how they search for the moral definition of the general interest. Your columnist limits his study to the political thinkers of social-democratic origin, because he is most familiar with these. A previous column has shown, that since the rise of the social-democracy four episodes can be distinguished. Although the classification is rather arbitrary, and other phase models are conceivable, the used analysis turns out to be fairly fruitful.

The leading social-democrats of all ages are supporters of democracy and of personal autonomy. In pluralism the social-democracy is time after time ideologically in the wrong. It is simply untrue, that the state is better in controlling the economy than the private entrepreneurs. Therefore since the fourth episode the traditional social-democracy has disappeared. Anthony Giddens introduces the agenda of the Third way, which is liberal and truly places the personal autonomy at the centre. Your columnist has again selected leading social-democrats, just as in the mentioned two columns. The aim is to test the preceding arguments on their accordance with reality, and to correct it, if necessary. The selected leaders are Hans van den Doel, Helmut Schmidt, François Mitterrand, Paul Kalma, Femke Halsema, and Gerhard Schröder.

In 1975 the Nieuw Links (New Left) icon Hans van den Doel wrote the book Demokratie en welvaartstheorie1. Here it concerns a scientific work, where Van den Doel attempts to integrate economics in the political and administrative sciences. As such the book fits well with the subject of this column. Van den Doel is definitely a representative of the third episode of the social-democracy. According to the welfare theory the state can increase the well-being of its citizens by developing its own suitable (policy-)target function U. The state can realize its goals by employing policy instruments such as the regulation of commercial markets and the redistribution of incomes. Nieuw Links wanted to improve the transformation W→U by maximizing the decentralization of the decision process and activating the citizens themselves (see p.21). However, Van den Doel concludes, that this participatory democracy has failed (p.10).

Therefore he tries to find new methods, that can strengthen the position of the politicians and their electorat. The target function U must allow for a minimum of paternalism (p.26). The interactions of individuals and groups can be modelled, for instance by means of game theory. This includes among others the democratic decision rules. The optimization of the transformation W→U is a matter of administrative organization. Van den Doel distinguishes between two forms of group organization, namely the hierarchic and democratic ones. The loyal reader may remember, that later the economist Paul Frijters has also made this distinction. The hierarchy is mainly employed in the execution of policies, that have been transferred to the administrative bureaucracy. The democracy is formed by the political system. The politicians have the important task to supply collective goods and services in a sufficient quantity.

Each political leader k presents his target function U(k) to the electorat, which chooses from this offer the one that best approaches their welfare function W. It is obvious that the target functions U(k) also contain the costs, since there is a scarcity of means for the realization of the policy. In the optimum the difference between the benefits and the costs is maximal (p.44, 95). Note, that it does not suffice to offer the maximum amount of collective goods. The economist P. Hennipman has already concluded, that the collective well-being is determined by the distribution of those goods (p.48, 74). In the political process the socially optimal situation can be reached, when the popular representatives mutually negociate and exchange interests. This is called logrolling, vote trading or package deals (p.57, 87). Here obstacles surface, such as limited information, or unequal relations of power.

Besides in the democracy the phenomenon occurs, that not all people will participate. For, the participation requires an effort, which is experienced as a cost (p.62, 100). Some citizens prefer a positive apathy, that is to say, they trust that the others will make the right decision. The loyal reader of the Gazette may remember, that the PvdA-politician T.A.M. Wöltgens has also pointed to this aspect. However, others indulge in a negative apathy, namely when they believe that their vote will not influence the result. The PvdA under Nieuw Links chose in favour of politization and polarization, exactly in order to mobilize the negatively apathic citizens. This is based on the sociological analysis of Karl Marx, who expects a growing revolutionary conscience of the exploited groups. Nevertheless, in reality merely a small minority turns out to be prepared to truly carry the burden of participation.

Thus there is a political elite of parties k, each with her own target function U(k). The top of these parties disposes over much power, and therefore forms an oligarchy (p.77). Now the organization of the democracy determines how the citizens will make collective decisions. Some forms of organization lead to an unstable system. This occurs for instance in a multi-party system, when the parties can not be clearly ordered according to a left-right spectrum. For, then all kinds of coalitions are possible. A strongly polarized society will also become unstable (p.79). A two-party system has the advantage, that it is always stable. However, a disadvantage of this system is, that the two parties can both position themselves in the electoral centre, in order to maximize their electorat.

Logrolling occurs partly within these two parties. In this exchange minorities with an intense preference can often be successful, namely when the majority is rather indifferent. This type of compromise increases welfare. Thus logrolling softens the dictature of the majority, which in principle is the foundation of democracy (p.86). At the time Nieuw Links truly attempted to organize the Dutch politics in two blocks2. A problem of democracy is that a policy for the long term is difficult to realize (p.117). For, the time horizon of the citizens is rather short, and they will seldomly choose a politician k, whose target function U(k) yields benefits merely in the distant future. Incidentally, during the period between two elections the politician does have the opportunity to decide according to his own views. Furthermore, the voters are not particularly knowledgeable, and that leads to wrong decisions.

The SPD leader Helmut Schmidt belongs, together with the Englishman Tony Blair, to the most succesful social-democratic politicians, certainly when merely the large European states are considered. This paragraph analyzes the book Auf der Suche nach einer öffentlichen Moral by Schmidt, which fits well with the theme of the column3. Although Schmidt was formed politically during the second episode of the social-democracy, he is a typical representative of the fourth episode, thanks to his pragmatic character. So he was ahead of his time. Since he exactly came to power during the third episode, he was notably controversial within the German social-democracy herself. The German people as a whole have always held Schmidt in high esteem.

In his book Schmidt notably reflects on ways, that allow citizens to develop a personal autonomy. For, they must select one of the target functions U(k), that are offered by the various political leaders k. This question is particularly relevant for Germany, because half a century before the population had helped the mentally deranged politician Adolf Hitler to come to power. Schmidt has experienced fascism and the war by himself. Therefore he stresses in his book more the civil responsibilities and morals than the social rights. The personal autonomy and will-power can only prosper, when one disposes of a personal conscience. The realization of the general interest (as represented by the target function U) is only possible, as long as the citizens act with a sense of duty (p.192).

Nevertheless, Schmidt does not want to translate the civil morals into an ideology. Rather, universal virtues are important, such as belief, hope, love, reason, justice, courage, and the capacity to judge (see p.201). It is interesting, that Schmidt presents the virtues as a collective property (p.215). They are not prescribed by the state, but are internalized by each generation through the formation by the parents, through education, jurisdiction and health care, work in the enterprises, and obviously also through the politicians. Therefore the morals emerge at the decentral level, so that they are pluralistic. Incidentally, the morals change with place and time (p.178). Pluralism can only exist in combination with a tolerant attitude. Thanks to the universal virtues the people can indeed bring in that tolerance.

Although the morals live on mainly in society herself, yet the elite has an important function. For, the elite can give an example to the people by means of her behaviour. According to Schmidt it is a mortal sin, when politicans unilaterally further their own interest in their target function U(k) (p.64). The leading professional groups should formulate and maintain their own professional codes of conduct. Moreover, the elite must dispose of sufficient capacities to lead in a sound manner (p.67). Leaders must have the courage to resist, when their followers want to realize impossible desires (by means of their welfare function W, p.57). For, it is true that the policy must have a moral appeal, but it must also be effective. In all these respects Schmidt is clearly congenial to the christian democracy4.

His social-democratic orientation rests mainly on his preference for organized deliberations between the entrepreneurs and the trade unions. The operation of markets does not have her own morals. Egoism furthers the social decay. Schmidt demands that the entrepreneurs accept good terms of employment and see this as a general interest. And the owners must not desire an unlimited profit, but must help to finance the collective sector (p.182). The entrepreneurs must even show some feelings of patriotism (p.167)5. Solidarity is a natural part of the general interest. But otherwise Schmidt demands more freedom of enterprise (p.149). It is also striking, that he is confident and optimistic about the opportunities of technological progress (p.28 and further). He warns against irrational fears with regard to the future of man.

The standpoint of François Mitterrand can not be absent in a contemplation about the social-democratic views. Between 1971 and 1995 he was the most important politician of the French Parti Socialiste (in short PSF), which he himself helped to found. The present paragraph is based on his book Ici et maintenant, which he published in 1980, a year before the presidential elections, which he indeed has won6. In order to understand his arguments it is necessary to know, that at the time the Leninist party is still powerful in France. Mitterrand can only become president, when he succeeds in binding the Leninist voters. Besides, France under the rule of general De Gaulle has become accustomed to a large and powerful state apparatus. All this explains, why Mitterrand pleads in favour of large-scale nationalizations of the industries, and of more central planning, in a period when the other western industry states already prefer an increased use of markets.

In the same strain Mitterrand calls the program of the PSF a class struggle. In this way he bases the party ideals on the second episode of the social-democracy, which amounts to an ideological rearguard action. He calls the PSF socialistic, and avoids the term social-democracy, because in France she has too much a revisionist connotation. As said, at that moment the social-democracy in the northwest of Europe is since long in the third episode, where the market is merely managed at the macro-economic level. It is the task of the PSF to awaken the conscience of the workers, that they are being exploited (p.35). The target function U represents the popular will, which must be forced through against the ruling class (p.38). Therefore the policy of the PSF will be characterized by decentralization and by the self-management of the workers, obviously within the boundaries of the plan.

According to Mitterrand the PSF is not marxist. She does not consider the class struggle to be revolutionary, because it advances by means of elections. She even has no desire to change the state system, although it supplies the president with an excessive power. On p.124 Mitterrand rejects the social-democracy, because she want to regulate and institutionalize the markets. That is not sufficiently rigorous, and merely leads to a political impasse. The workers must themselves come to power. The enterprises must become democratic (p.169). Therefore the PSF in government will always remain in dialogue with the trade unions (p.135). Apparently here he proposes a concertation, just like the Social Economic Council in the Nederlands (p.168). The nationalizations are notably needed in order to make the high finance powerless (p.171). The core of the policy is the change of the productive relations (p.187). Capital must be state property (p.213).

Mitterrand wants to combat unemployment by reducing the working hours (p.200). The domestic market gets the highest priority, and the export will be limited. Regional investment banks will be established. The agriculture will be regulated, so that the farmers obtain a sufficient income. The agricultural land could be controlled collectively (p.143). Mitterrand distrusts the civil society, because she always represents a particular interest (p.180). Only politics represents the general interest. The education serves to increase the social mobility (p.153). She must impart a critical attitude, and create room for the personal emancipation. The television can be an important instrument for the stimulation of the individual formation. According to Mitterrand the well-being will rise thanks to informatics (p.210). Here he even predicts the coming of the mobile telephones!

According to Mitterrand innovation is essential for the economy. However, he believes that here the state must take the lead. In addition, science is not neutral, so that it must be supervised by politics (p.217). This sounds a bit authoritative. Nevertheless, Mitterrand acknowledges that a universal conscience exists, and for instance promotes the human rights (p.228). He defends the political liberty. By now it is clear, that he wants to limit the economic freedom of the small industries. For that reason, he is convinced that the European Economic Community (in short EEC) must necessarily become a socialist body (p.256). She must for instance supervise the exports.

It will now be clear to the reader, that Mitterrand advocates a radical left-wing course, which does not bear witness to much realism. Positive is the degree of autonomy, that he wants to give to the industrial workers. However, it may be doubted that this would indeed make them happy. Because, the state also becomes more powerful, so that he becomes an instrument of exploitation by himself. During the eighties the PSF indeed rapidly moderates her policies and standpoints. Thus it is conceivable, that al these audacious statements in Ici et maintenant merely serve to maximize his own following, just like the Schumpeterian pluralism. That is the transformation W → U in optima forma, albeit with misleading propaganda. It must also be concluded, that Mitterrand barely tries to bend the expectations of his followers into a more realistic direction.

For several decades Paul Kalma has ideologically played a leading role in the Dutch PvdA, even to such an extent, that he can be called a party ideologist. In 1988 he wrote the courageous book Het socialisme op sterk water, which is an ideological turning point, and therefore deserves attention here7. Namely, in this book Kalma provides the ideological underpinning for the fourth episode of the social-democracy, ten years before the publication of The third way by Anthony Giddens. The message is the same, namely that socialism is outdated as an ideology. It is true that this was already apparent due to the pragmatic course of social-democratic leaders such as Helmut Schmidt and Wim Kok, but certainly in the Netherlands the rank-and-file were barely able to assimilate this idea. In the present paragraph the analysis focuses again on the design of the political process W → U.

According to Kalma the west lives in a social capitalism, where many ideals of socialism have been realized. However, a number of elements of socialism (the universal nationalization of the industries, workers' self-management, etcetera) are principally unsound, and therefore the social-democracy must abolish them. The PvdA has failed to do this, and in this way has become politically isolated (p.13). Notably, Kalma thinks that politization and polarization are very hurtful for the democracy and for the PvdA (p.26)8. Here he flatly contradicts the just described ideas of Van den Doel. Polarization may be an option in a system with electoral districts, such as the France of Mitterrand. But in the Netherlands the division in two is only achievable through an unrealistic extremism. And Kalma prefers a moderate and solid course. The PvdA must again become a natural partner in government (p.18).

According to Kalma the modern social-democracy has two pillars, namely the legal order of labour and the democracy. Here one recognizes the view of Schmidt, who also attaches value to the order. And just like Schmidt, Kalma rejects the lack of engagement and the libertarism of Nieuw Links (p.21). Politics does not dictate the social morals. The social system is essentially pluralistic (p.37). Incidentally, it is hardly possible to compromise about ethical subjects. Thus Kalma sees no sense in the slogan "Changer la vie" of Mitterrand (p.21). Politics must restrict itself to the design of smart target functions U(k) for the general interest (p.29, 34). And precisely the social questions are fit for political compromises, because the socio-economic interests are mainly material in nature (p.60, 140). Solidarity is an enlightened self-interest (p.47).

Thus the emancipation and the personal autonomy develop partly within labour itself (p.62). There is a compromise between labour and capital, but also between the various groups of wage earners themselves. Kalma even states that capitalism is a necessary condition for the political democracy (p.81). In this respect he is close to liberal economists, such as Paul Frijters and Daron Acemoglu. The state facilitates the deliberations between the various interest groups (p.82). The collective sector is a part of this arrangement. The ordering by the state is restricted to the socio-political domain (p.91).

The second pillar of the social-democracy is democracy. Kalma criticizes the participation ideology of the PvdA and of Nieuw Links. That ideology wants to rigorously restrict the autonomy of the official bureaucracy, and to excessively subject her to the people's representatives. Thus the parliament wants to participate in the execution. In the paragraph about the ideas of Van den Doel it became apparent, that in this manner Nieuw Links tries to make the functions W and U coincide. According to Kalma this is inefficient and even impossible. The attempt of Nieuw Links has hardly produced any results, because the willingness to participate has been overestimated (p.112, 119). Therefore, according to Kalma, the parliament must restrict itself to controlling the execution of policies. Thus the official bureaucracy regains some policy freedom. That furthers the efficiency.

This paragraph is concluded with a short analysis of the present-day view of Kalma. It is true that although he has always promoted the independency of the state enterprises, and more effectiveness and efficiency, he has always rejected the privatization of the state enterprises. Nevertheless the state has often preferred this option. Apparently Kalma can not accept this. He believes that in the contemporary economic system the legal order of labour is fundamentally affected. Because recently he has published the book Makke schapen, where he promotes a return to politization and to polarization (p.137, 159, 235)9! Your columnist dislikes polarization still as much as in 1988. The transformation W → U can only be optimal, as long as all are willing to make compromises.

The irritation of Kalma is so great, that in his last book he reproaches the PvdA that she would have become a party of administrators (see p.9 there, and 209). In Het socialisme op sterk water he proposes this as the central goal! And whereas previously Kalma advocated effectiveness and efficiency in the public sector, on p.101 of Makke schapen he complains about a "merchant spirit", and about an undesirable "primacy of financial and organizational calculation" (see also p.190). Whereas previously he demands a "business-like attitude", now politics would have assumed an undesirable "technocratic character" (p.107 MS). On p.180 Kalma even promotes a return go the cultural socialism (see also p.231). Perhaps this is all understandable, considering the subjective perspective of Kalma, or he may consciously choose to exaggerate. But for dissentients his change of mind is naturally extremely confusing, and not very credible.

At first sight Femke Halsema does not fit well in this column about social-democratic policy. However, since the nineties of the last century the ecological movement, consisting of the green parties, and the social-democracy have become more similar. When the opportunity arises, they like to form a coalition. Therefore your columnist thinks it is worthwhile to analyse the philosophical ideas of Halsema. The present paragraph is based on her books Linkse lente (written together with M. Zonneveld) and Geluk!10. The view of Halsema is fairly simple: the society has become too materialistic. This has the consequence that the people work too hard. They would be happier, if the labour intensity would diminish. There are scientific clues for this, among others in the publications of Richard Layard (see p.66 in Geluk!).

Halsema believes that working hard is dictated by the capitalist culture. People use consumption as a way to express their identity, and this habit is reinforced by advertising. Therefore the wage level is important for people. They keep trying to raise their labour productivity. The ambition to be effective creates an atmosphere of competition, also in the public sector, which traditionally rather ignored performance. Gradually mechanisms of market operations have also been introduced in the public sector, so that a culture of merits has emerged. Henceforth the execution of the activities is supervised bymanagers, who continuously strive for better results. Following the industrial Fordism there is a continuous search for advantages of scale. However, professional groups such as teachers, nurses and police officers feel rushed by the new pressure for efficiency.

Moreover, Halsema states that the quality of the offered services suffers from the high production. The workers in services no longer have time to chat with their customers. Therefore she wants to stop this development, namely be rigorously downsizing the layer of managers. Mutual trust is a social capital (p.106 in Geluk!). The professional groups can supervise their own performances. They are the true bearers of justice and solidarity. When nonetheless the need arises to make the executive organizations accountable, then that is the task of the people's representatives. Furthermore the social justice requires, that the distribution of incomes become more egalitarian. Perhaps such measures will slow down the growth of the gross domestic product (in short GDP), but this is a bad indicator for human happiness. The quality of living is more important.

When people moderate their consumption, then this benefits their personal emancipation and autonomy. For, these are immaterial benefits. Halsema expects an increasing self-organization and awakening, and refers to the seventies of the last century (p.86). Incidentally, she does add new elements to the then kind equality. Notably, Halsema states that the state must do more to activate its citizens. On p.146 of Linkse lente she promotes the abolishment of the protection against discharge, and an unemployment benefit with a duration of at most a year. The long-time unemployed obtain a participation contract with a minimal income. Then the labour productivity is less relevant (p.123 in Geluk!). The workers must obtain various opportunities for paid and unpaid leave.

In short, the traditional entrepreneurship must be bridled. That is accompanied by a cultural change, that for instance removes the advertising from the public television channels (p.146 in Geluk!). Henceforth, the society must become less materialistic. On p.75 of Linkse lente Halsema denies the existence of a popular will, that is to say of a clearly identifiable welfare function W. Therefore she is convinced that politicians must formulate their own target function U. On p.155 in Linkse lente she pleads in favour of "politicians who distinguish themselves by an independent attitude. Who do not desparately try to please their followers". Your columnist is not completely reassured. Too often, a political caste has dictated its ideals of austerity on society, searching for the "new man"11. Again and again the citizens turn out to voluntarily prefer the materialistic way of life.

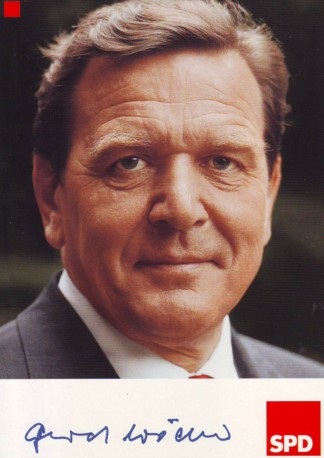

About ten years after the start of the fourth episode Gerhard Schröder, who is a pre-eminent representative of the social liberalism, becomes the leader of the German social-democracy. During the years 1998-2005 he keeps the SPD in government, in a coalition with Bündnis'90/Die Grünen, and himself occupies the position of chancellor of the federation. In this manner he proves that the reformed social-democracy is electorally successful. Incidentally, in 1997 in England, New Labour also wins the elections, with a similar program. Shortly before the elections of 1998 Schröder explains his views in the book Und weil wir unser Land verbessern ... (a citation of Bertold Brecht)12. There he gives a clear insight into the hallmarks of the modern social-democracy.

Although Schröder accepts the political construction of society, he believes that the operation of markets is the best manner to guarantee the general well-being. The industries are sensitive to the desirable allocations and opportunities for investing. An important pillar for the social-democracy is the tripartite deliberations between the trade unions, the industries, and the state. He praises his congenial Karl Schiller, who thirty years before as the minister of finance was successful with the concertation. Schröder would like to found a Stichting van de Arbeid, such as in the Netherlands. That would institutionalize the corporative structure in the economy (see p.30). The conclusion of collective labour contracts (in German called a Tariff) is a good instrument for maintaining the labour peace, and for raising the productivity. Schröder promotes a participation society, where labour is justly rewarded.

Participation implies that people are activated by the state, if need be. For, individuals must be addressed with respect to their responsibilities. The social security must be a trampoline (p.58)! Flexible forms of labour can offer advantages to all concerned. In general Schröder prefers a supply side policy, where the aim is an efficient production. Profit is desirable, at least as long as it leads to investments. In this model the partial coverage of pensions by means of capital fits well. This also accomplishes, that property is more equally distributed within the society. Thus a "patient" capital is accumulated. The state guards over the morals, and realizes tasks that can not be done by the private sector (p.39). Morals are in essence a procedural consensus about the way to promulgate legislation, and to exercise power. Schröder calls this constitutional patriottism.

Thus the democracy is a system, that must be learned and maintained (p.195). The paternalistic state is not acceptable (p.197). This even holds for the executing apparatus, which is best made independent, because then the efficiency increases (p.217). Within this system regional groups with their own culture emerge, but with an open character. The starting point is equal opportunities. Everybody has the right to be optimally educated. But the education must correspond to the economic needs, in order to maintain a generous wage level. For, the supply side policy requires, that the wages follow the productivity (p.206). Young people must learn a dynamic and enterprising attitude (p.119). Furthermore, the individual responsibility requires, that the society is intolerant with regard to crime.

Interesting is also the view of Schröder on politics. Due to his preference for the procedure he is less interested in the party program. The democracy would survive, when the voters would choose a person (and his ideas) instead of a party (p.143). He likes the media culture, because media are a useful mouthpiece for the politicians. The democracy evidently requires, that the policy of the state is supported widely within the population (p.154). Then the target function U will resemble the welfare function W. A hallmark is the pragmatic approach, free of dogma's, for instance in environmental policies. Again and again Schröder prefers the road of gradualness (p.162). The industries and investors also have a right to security.

A year after the appearance of his book Schröder writes, together with Tony Blair, a manifesto with the title Der Weg nach vorne für Europas Sozialdemokraten. Schröder translates the third way for his German voters as die neue Mitte. The hallmarks are justice, equal opportunities, and solidarity. The general interest requires efficiency and profitability. The globalization and the innovation demand of all a maximal flexibility. The entrepreneurial spirit returns in the social-democracy, while leaving room for concertation. The production factors capital (investments) and labour are taxed less than before. The demand side policy must be merely supplementary. The quality of the public services is subjected to a rigorous supervision. Here the manifesto allows for national nuances. This reformed type of social democracy has definitely been successful: remember the Purple cabinets (in the Netherlands) and the New Democrats (in America).

In this column several new insights have been gained about the transformation W → U. Van den Doel describes how the democratic system functions. The say of the citizens is partly determined by the institutional construction of the system. Apparently Van den Doel prefers the two-party system with logrolling. According to Schmidt it is essential for the society, that the population always transfers solid morals to the next generation. He recommends to act according to the Golden Rule. Next attention has been paid to the program of Mitterrand, a contemporary of Schmidt. The French program stems partly still from the previous episode, with a call for class struggle and even a policy of nationalizations. It is difficult to image that Mitterrand himself believed in his program. Therefore this example illustrates, that political leaders sometimes hold out illusions in order to win elections.

Kalma states in 1988, that the target function U of socialism is unsound. He recommends to henceforth develop pragmatic and matter-of-fact policies, so that the party can truly participate in government. The welfare W of the citizens is guaranteed by an order of labour and by democracy. Halsema differs somewhat from the preceding politicians, because she has a rather paternalistic attitude. The citizens can be manipulated easily, which has the consequence that their welfare function W is unsound. Therefore Halsema does not really base her target function U on the W of the voters. She aims at a revolution.

Schröder is an adherent of the social liberalism, just like Schmidt and Kalma. Without any embarrassment this current vies for state power. Besides, it aims at some order, in order to guarantee the interests of the factor labour. But it does not hesitate to point out the boundaries of the achievable, if needed. Within these mainly economic boundaries the citizens obtain much freedom, and thus the entrepreneurs as well. Schröder calls this view a constitutional patriottism: everybody acknowledges the fundamental rights, and is willing to compromise. Apart from that everybody is free to determine his own morals.