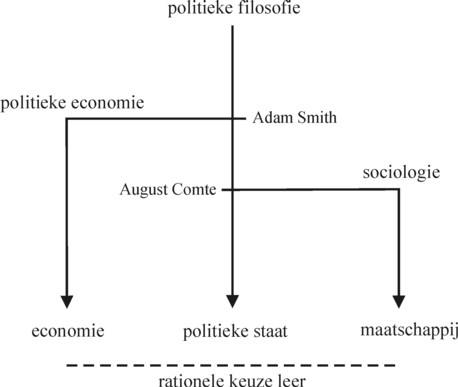

Figure 1: Social sciences

Several recent columns focus on the rational choice paradigm (RCT) of Coleman. The present column makes some annotations with regard to his theory, notably originating from the social psychology. Thus the social sciences are integrated better. The learning model of Kolb shows the dynamics in the individual cognition. The RCT can be complemented with models of group structures. It is also desirable to take into account the various motivations and principles of distributive justice. And finally not all means are entirely commensurable.

The Heterodox Gazette was founded as the result of discontent with the rather dogmatic picture, that the neoclassical economy uses for modelling reality. Various other economic paradigms are at least as interesting. Incidentally, relevant information can also be found in the other human sciences, such as political sciences and sociology, and at a more fundamental level the psychology and philosophy. Exchanges do not just occur on market, but also in all kinds of social situations. It is unwise to get carried away by the inclination of economists to decouple their discipline from the other social sciences. In the present column the mutual relations between these sciences will be studied first.

In several recent columns attention has been paid to the social exchange. It turns out that many immaterial resources can be exchanged and traded just as well as the commercial products. The American sociologist J.S. Coleman has made a profound theoretical analysis of the social exchange in his book Foundations of social theory (in short Fost)1. Here he chooses to apply the rational choice theory (in short RCT). It turns out that his discipline party overlaps with the social psychology. Although Coleman was probably aware of this, he yet mostly tends to ignore psychology. The present column will try to clarify the models of Coleman by comparing them with the knowledge of the social psychology.

In this paragraph it will be summarized how the sociologist D. Pels explains the relations between the social sciences. He analyzes them in his readable book Macht of eigendom?2. The foundation for the social sciences has been laid by the political philosophy, where one can go back to the times of Aristoteles. At the end of the eighteenth century there is a secession due to the ideas of the Englishman Adam Smith about political economics. The sociology secedes a few decades later from the political philosophy, when the Frenchman Auguste Comte publishes his studies. Henceforth there are three spheres of human activity, namely the political state, the economy, and society3. Whereas economics is accepted rapidly as a separate sphere, the sociology must make a significant effort for marking out her own domain of study.

The mentioned development is presented graphically in the figure 1. For the loyal readers of the Gazette the economic pillar does not need a further explanation. This is different for the sociological pillar. Comte actually wants to just broaden the political science. The political regime naturally steers the social developments in a certain direction. But Comte states, that conversely the state must always take into account the society. Here one recognizes the remarks, that Coleman makes with respect to the interaction between the micro- and macro-level. The intimate intertwining of the state and the society makes it difficult to study them separately.

Later the German Max Weber has contributed much to the development of the sociology. He also observes the three mentioned spheres of human action. Each sphere has its own groups, which mutually compete for power. Thus political parties form in the state, classes form in the economy, and status forms in society. According to Weber the spheres are mutually independent. So there is no power in the last resort, unlike Marx, who defines the economic sub-structure as the all important factor. Weber believes, that human actions benefit from rationality, and uses this hypothesis to construct his theory of organizations. He was one of the first to observe the rise of the employed managers, who take over the direction of organizations from the capital owners and the nobility. The managerial revolution heralds a new phase.

Shortly after Weber the Frenchman Emile Durkheim also became authoritative. Durkheim tries to increase the prestige of the sociology. He is influenced by the French thinker C.-H. de Saint-Simon and by the German Historical School. Therefore it is not surprising that Durkheim uses the sociology in order to connect the morals, politics and economics. Although he accepts the modern industrial state, yet he wants to reform it. The property must serve the society. Therefore he has more confidence in politics than in the economic operation of markets. He believes that the state can establish morals by organizing the economy in a corporative manner.

Although the sociology has generated several great thinkers, Pels still finds it difficult to clearly demarcate its domain of activities. Nowadays it is often stated, that the sociology studies moral communities and groups. Notably processes of power are analyzed, where often the economic property is not decisive. Therefore Pels believes, that the sociology has remained intimately related to politics. Here your columnist sees an agreement with the theory of Coleman, who makes the concept of property immaterial by coupling it to the right of control. Power is the control of various resources. In this manner the economic operation of markets is just one method of interaction among many others. Therefore your columnist has depicted the rational choice paradigm below in the figure 1, as a connecting link between the three scientific spheres.

Strictly speaking the explanation of Pels is not complete, because he remains silent about the psychology. The psychology introduces the sphere of the individual life, at the micro level of society. This is precisely also the domain of the rational choice theory (RCT), so that it is worth analyzing her relation with the psychology. In this column notably two books are consulted, namely De kern van de sociale psychologie (in short Dkvdsp) and Groepspsychologie (in short Gp)4. The sociology studies the influence of society on the individual actions. The group psychology is the part of this, that concentrates on group processes. First, as an introduction of the argument, the theory of experience-based learing of D.A. Kolb is described5.

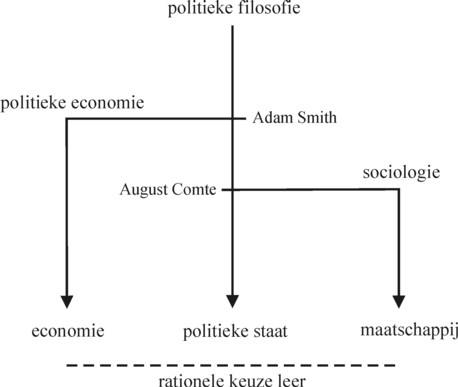

According to Kolb, learning is cyclical, namely decide → do → evaluate → think → decide once more, etcetera. The cycle is shown in the figure 2. Suppose for the sake of convenience that there are N actors (i=1, ..., N) and M goods (j=1, ..., M). The decision is based on a certain cognition, in other words, preferences xji of the actor i with regard to the good j. The action leads to a concrete experience, because she provides the actor i with certain quantities cij of good j. In the evaluation phase the experience is evaluated. This phase leads to a correction of the personal ideas and preferences, namely in such a manner that a next time the action will generate more utility u(xji, cij). After the evaluation and adaptation of xji a new decision can be made.

The individual learn to act optimally within his social environment. The environment influences his behaviour by means of rewards and punishments. Apparently, in the learning cycle the rewards cij and the cognition xji are integrated. It does not suffice to get ideas merely from a book. The four phases are located at various places in the cross of axes, which is also shown in the figure 2. The decision is clearly an active act, even though it is rather abstract. She is made concrete during the action. The phase of evaluation is still concrete, because the experiences must be ordered. However, she abandons the action, and becomes a reflection. Finally, the correction or adaptation of the personal cognitive frame is again highly abstract6. Notably the alternation of concrete and abstract processes contributes to the personal development.

The learning model of Kolb can also be applied to groups, such as organizations. Thus for instance the political cycle can be modelled, in the manner of the column about social norms. The parties in government make a policy plan, based on their ideologies. The execution results in a certain satisfaction of the needs of the people. During elections the people will express their satisfaction with the policy results. Next the government adjusts its plans, perhaps after forming a new coalition. Another application of the learning model of Kolb is the planning of organizations, varying in size from the separate enterprise to the state. Note that the rational bureaucracies, which made Weber so enthusiastic, commonly do not learn very well. They are meant to execute a fixed described task in an efficient manner.

The RCT does not discuss planning, because according to her the decisions are always made at the micro level. They are the result of a massive exchange process, that is difficult to survey. However, Dkvdsp does analyze the planning process (p.66). Planning requires the dissection of the target or task in sub-tasks, which each correspond to a sub-plan. This is similar to the planning theory of the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen7. Both an individual and a group can develop their own plan. According to the Test Operate Test Exit model (in short TOTE) the (sub-)task or (sub-)action is repeated, until the planned (sub-)target has been realized. In other words, the TOTE model represents a regulation system with feedback. Its advantage is that the (sub-)tasks must be formulated clearly and amenable to measurements. The order of all these TOTE schemes assures that the sub-plans are connected well to each other.

Planning is useful for the individual. However, it displays its largest utility, when it is used for realizing complex goals. Notably the goals of groups belong to this category, and then these tasks are a part of the macro level. Many are involved in the realization of the end target, where almost always some division of labour is introduced. The psychology calls this differentiation. The individual turns his assigned sub-plan into an end-target. In the case of a group plan naturally some coordination is necessary, so that everybody knows his sub-task. An organization is required, which regulates the relations between the group members, and thus structures the group. This is called integration. Indeed the TOTE model fits well with a bureaucracy, and that explains why for instance Max Weber (or Tinbergen) were so enthusiastic about bureaucracies.

In the rational choice model little attention is paid to the organization structure. And loyal readers understand why this is so: the hierarchy suffers from the principal-agent problem. For this reason Coleman states on p.421 and further in Foundations of social theory (Fost) that the bureaucratic structure of Weber is unsound. Weber assumes without justification that the end target of a group member coincides with the sub-task, that has been assigned to him by the group. In reality that group member always has his own interests, and he will not simply abandon them in favour of the larger group target. Apparently the rational organization of groups requires a different approach than the bureaucratic structure. Nevertheless, Coleman does recognize, that some structure is indispensable8. And indeed the structure of groups remains an important subject of study in the social psychology.

Incidentally, Dkvdsp and Gp barely mention the principal-agent problem. This is explained partly, because the concept is typically economical. Another explanation is that the social psychology mainly studies groups, where from the beginning the members are equal. It wants to study the structure, that the group will voluntarily choose, when she must execute a given task. Here each group member wants to maximize his reward, and minimize his costs. See chapter 8 in Dkvdsp. The Dutch economist P. Frijters calls this the reciprocal group. In this case the group must first deliberate on the optimal structure. Only after making this decision, the task can be executed. In this manner the social psychology also analyzes which structure gains the most social support.

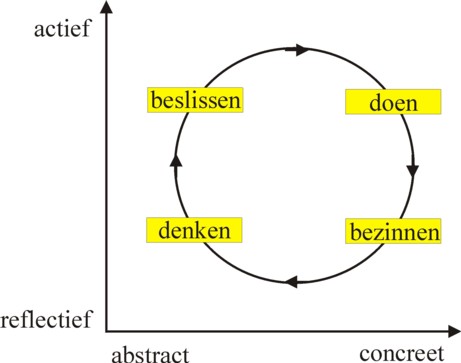

In the social exchange of the RCT all group members can trade freely with each other. The social psychology calls this an all-channels network. However, those who want tot analyze the influence of the structure on the individual actions, are well advised to also study the circle network and the wheel network. In the circle each group member merely has two channels for communication or exchange. In the wheel there is a leader, who has channels to all group members. The leader is located in the position of the wheel axis. A special case of the wheel is the chain or line. The figure 3 displays all of these networks. The all-channels network and the wheel are fundamentally different. In the first case everybody occupies the same position in the communication structure. Everybody is equally powerful. On the other hand, the wheel delegates the control of the communication to the leader. He determines how the information is distributed, and this gives him much power.

Laboratory experiments show, that for the case of a simple task the group commonly voluntarily chooses the wheel structure. Namely, it turns out to perform best, and all group members profit from that. On the other hand, for more complex tasks the group forgoes much differentiation, and maintains a network with decentral communication. Some psychologists state, that in this case the wheel network would fail, because the burden of the leader would be too large9. According to others, the wheel network is not formed, because its establishment requires an effort. Then the group believes, that the costs of structuring does not match the expected later benefits during the execution of the task. This suggests, that the wheel network is useful for all routine tasks, also the complex ones. Experiments indeed show, that a circle network must make an extraordinary effort for restructuring into a wheel network (p.178 in Dkvdsp).

However, these experiments also show, that the introduction of a hierarchical structure causes discontent with the group members in the lowest positions. They believe that the structure is unfair, and feel hurt in their interests. This is a brake on the transformation of the circle into the wheel. All members in the circle try to conquer the leader position on the axis. Reconciliation is conceivable, when the leader has special talents and can be elected by the group members together. For, then they expect, that the group under his direction will realize better outcomes. These empirical finds illustrate again the principal-agent problem. They also support the MAR model of the social-psychologist Mauk Mulder10. For, that model states, that people strive for minimal differences of power. According as the power differentiation increases, the resistance of the less powerful will increase, for instance by means of block formation into a sub-group.

In a previous column it has been explained that Coleman studies the social exchange mainly in a perfect system. The perfect system resembles an economic market, with as a difference that now the traded goods can also be indivisible. A social system commonly allows bargaining about the exchange value vj of a good j. However, the perfect system has the hallmark, that the exchange values (or at least the exchange ratio vj/vk of two goods j and k) is fixed in a unique manner. Thus the system is in a unique competitive equilibrium. It has been theoretically proved that such an equilibrium is truly present for a system with an arbitrarily large number of suppliers and buyers.

However, Coleman also assumes the presence of a unique competitive equilibrium in a system with merely a handful of actors. This is somewhat strange. If your columnist understands Coleman well, then in this situation the equilibrium is guaranteed by the assumption, that the social exchange must not change the richess ri of any actor i. That it to say, the quantity ri = Σj=1M cij(t) × vj is constant for each time t. Coleman does not elaborate on this point, but the assumption is indeed defendable. For, durability requires justice. For, suppose that a powerless actor i is continuously forced to agree with an exchange ratio, that would continuously reduce his richess ri. Then finally i will lose all his richess. Apparently such a situation is not durable. It can be said that the perfect system is based on the principle of constant richess.

The social psychology pays much attention to the principles, that actors apply during their mutual interaction. See p.114 and further in Dkvdsp, and chapter 6 in Gp. As long as the number of actors is limited, there will always be a certain mutual relation of power. The reason is, among others, that in such a situation some actors are exclusive suppliers or buyers. They are in a monopoly position. Each power structure requires, that principles of distributive justice are formulated. A principle is a social norm, which can be invoked. Since each break of the principle is punished, it gives some power to the powerless. It offers some protection against abuse. The enforcement of the principle can require, that the powerless individuals organize by forming a coalition or sub-group (p.121 in Dkvdsp).

The social psychology distinguishes concretely between the principles of justice, of equality, of need and of ego. The justice or fairness principle assumes, that a transaction leads to a fixed ratio of the yields and costs for all actors i (p.117 in Dkvdsp, and p.92, 101 in Gp). When the costs are higher than the yield, then the transaction will probably not be concluded. When the costs exactly cover the yield, then the welfare remains equal, and there is in fact the principle of constant richess, which Coleman uses. However, the yield can surpass the costs, and then the economy is growing. The principle suggests, that for everybody the same profit rate holds. Justice means that the exchange is balanced, and that furthers the mutual collaboration.

There is obviously discontent, as soon as the principle is broken. There are two ways to reduce the discontent. Most obvious is changing the distribution in such a manner, that the principle holds again. Then the cij are corrected. The second manner is to change the cognitions xji. For, the utility of a good j is given by xji × ln(cij) 11. In the mentioned column about the perfect system it is shown that the actor i will attach more value vj to the good j, according as xji increases. For instance, a powerless actor, who wants to acquire a good j, but who objects to the height of its price vj, can convince himself that the good is more attractive than he thought at first. Note that here the price vj is an instrument of power for the supplier of the good j. The heigher vj is, the more his richess increases (p.112 in Dkvdsp).

As an alternative the powerless actor can on reflection reject the good j in a cognitive manner (xji = 0). Then this exchange is not completed, and he can search for a more reasonably priced good k, that he likes. Note here, that the cognitive adaptation also occurs in rules of thumb such as: "Everybody gets what he deserves". The principles of equality, need and ego are less obvious, so that it is understandable that Coleman ignores them. The equality principle gives all actors an identical yield. This principle gives up the coupling of the costs and yields. Consider a fixed hourly wage in the collective agreement, which does not take into account differences in performance. It requires a society with a certain harmony, where inequality is believed to be objectionable12. In its ultimate consequence this principle leads to the egalitarian distribution, where the utility of all is the same.

When the society is altruistic, then it can choose the principle of need. This allocates the goods in accordance with the existing needs. Here the relation between effort and reward is apparently completely missing. The more active actors must find their reward in the social love (the service motive, for instance in the aristo-democracy, or the performance motive). The personal utility extends to others, which are included in the personal identity. Therefore the principle must be internalized by the most powerful actors. Conversely, the ego principle implies that the actor only takes into account his narrow self-interest. This occurs (by definition) mainly in systems with a weak social cohesion. They are characterized by a continuing struggle for power, which hurts the total social outcome (p.126 in Dkvdsp).

Each principle from the preceding paragraph is characteristic for a certain type of society. Before such a principle is formed, the individuals must separately become convinced of its soundness. That again happens during a learning cycle, similar to Kolb. For, the actors commonly have partly conflicting interests. In the psychology this is called a partial correspondence. There must be built trust, and some predictability. The RCT of Coleman can indeed calculate such situations, but she does not offer much insights into the underlying psychological processes. Therefore the social psychology is a welcome supplement. Incidentally, it must be noted here, that similar studies of behavioural strategies are conducted by behavioural economics. Here one also has an inter-disciplinary field of analysis.

Trust can be built in a relation of conditional cooperation. This is studied by means of the game theory. Consider for instance an exchange or interaction between two actors. As soon as one actor chooses for egoism, the other actor will punish him, for instance by also becoming egoistic (chapter 6 in Dkvdsp). The two actors must realize, that they are mutually dependent, because of their needs. Moreover, they must predict how the other will behave. One may remember the reciprocity model of Rabin, which is known from behavioural economics. Incidentally, the model is not found literally in Dkvdsp. But it is applied again and again in the presented arguments. The concerning utility function is repeated here

(1) u(SA, SB, S'A) = XA(SA, SB) + α × f(SA, SB) × g(SB, S'A)

The formula 1 describes an interaction between two actors A and B. Each actor I (with I=A or B) uses a strategy SI, and with it realizes a material outcome XI. The strategy S'Aexpected from him by the actor B. The function u is the utility, that the actor A gets due to the transaction. The function f is the altruism- or kindness-function of A. The function g is the expectation of A with regard to the altruism- or kindness-function of B. The functions are positive for altruistic individuals. The constant α expresses the inclination of the actor A for choosing reciprocity. A homo economicus misses that inclination, and therefore has α=0. However, true humans experience joy due to reciprocity (f), and even more when it is reciprocated (g). Conversely, a refused altruism (f>0, g<0) causes feeling of discontent and dislike.

The formula 1 is purely empirical, and not based on profound theories. First, note that it is not valid for a hardened altruist. For, suppose that A adheres to the need principle, whereas B uses the ego principle. Then A will be ruined, although perhaps his utility will not suffer from that13. For, such an interaction leads to a continuously decreasing XA and an increasing XB. This case illustrates that conditionality is essential. The actor A must try to use the functions f and g for modelling the intentions of B. Experiments show, that actors with a cooperative intention indeed often cooperate. The cooperation yields a reward, which reinforces the behaviour. Conversely, cooperation is difficult for aggressive actors (p.106 in Dkvdsp).

The preceding arguments concern transactions at the micro level, where a social principle is still absent. Therefore there is no fixed exchange ratio. A compromise must be made by means of communication. One needs to bargain, where the mutual power determines the result. As a conclusion of this paragraph it is interesting to reproduce a game situation, which has been presented on p.128 of Dkvdsp. See the tables 1a and 1b. They show that the outcomes of a transaction can change due to the intentions of the two actors. The actors A and B can both choose an option 1 and an option 2. The most left-hand 2×2 matrix in the tables 1a and 1b shows the actual material outcomes (XA, XB) for respectively the actors A and B.

| actual | A and B altruist | A altruïst | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B option 1 | B optie 2 | B option 1 | B option 2 | B option 1 | B option 2 | |

| A option 1 | 8, 4 | 2, 2 | 4, 8 | 2, 2 | 4, 4 | 2, 2 |

| A option 2 | 2, 2 | 4, 8 | 2, 2 | 8, 4 | 2, 2 | 8, 8 |

In the table 1a, A and B benefit from both choosing the same option. Here A benefits most, when they choose option 1, whereas on the other hand B obtains his maximal outcome for option 2. However, this changes, when A and B are both altruistic. For, then the personal reward is derived from the outcome of the other. Therefore the preferences of A and B switch. It is remarkable, that in this situation there is still no agreement (correspondence). Apparently a social norm is not yet a guarantee for harmony. In the case that only A is an altruist, the preference of B is still determined by his own outcome. This is pleasant to such an extent, that now the maximal outcomes of A and B coincide, namely in the transaction where A and B both choose the option 2. Bargaining is no longer necessary.

| actual | equality principle | A equal, B aggressive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B option 1 | B option 2 | B option 1 | B option 2 | B option 1 | B option 2 | |

| A option 1 | 8, 8 | 3, 0 | 0, 0 | -3, -3 | 0, 0 | -3, -3 |

| A option 2 | 5, 7 | 0, 3 | -2, -2 | -3, -3 | -2, 2 | -3, 3 |

The actual outcomes in the table 1b are different from those in the table 1a. In principle A and B will both choose their option 1, because this makes their outcome maximal. When both actors accept the equality principle, then their optimal choice will not change. However, the outcome decreases. For, they do not care what the outcome is, as long as they are equal. When on the other hand B has an aggressive attitude, then he maximizes his utility by maximizing the difference in outcome with A. Whereas in the two preceding situations of the table 1b agreement is reached, now the aggression of B is irreconcilable with the equality preference of A.

Philosophers like to assume, that the various needs are not mutually comparable. Formally expressed: they are not commensurable. Ethical issues must have an absolute validity, so that material interests have to give way. Thus it may happen, that in a transaction the intentions of the actors are more valuable than the outcomes. When this would be right, then it is difficult to understand how actors can maximize their total utility. Therefore Coleman prefers to make in his RCT all needs commensurable. The social psychology has tried to develop rules of thumb for such situations, partly based on experiments. They are called something-for-something rules (p.143 and further in Dkvdsp).

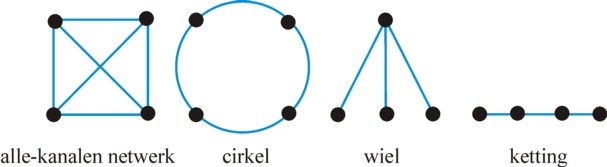

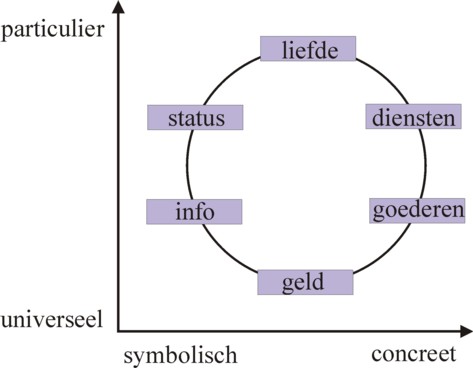

In the model of Foa and Foa there exist needs for six types of outcomes, namely: information, status, love, services, goods, and money. They differ in two dimensions. Firstly, some outcomes are more concrete than others. The less concrete outcomes mainy have a symbolic value. And secondly, some outcomes are more personal (or particular) than others. For instance, information is neither very concrete nor very personal. Conversely, services are very concrete and personal. These differences are drawn schematically in the figure 4. People do not like to exchange an impersonal object against a personal object. They also dislike exchanging a symbolic outcome for a concrete one. They strive for transactions, where preferably comparable outcomes are exchanged.

The preceding argument does not exclude, that sometimes incompatible objects are exchanged, notably when they are fairly universal (impersonal). However, this will happen mainly for outcomes, that in the figure 4 are located next to each other on the circle. For instance this explains why actors are willing to exchange money for goods. The model of Foa and Foa is agreeable for the RCT. For, the transactions on the market can occur, without explicitely taking into account symbols such as status effects. For, the personal outcomes of status and love have a very high price. Nevertheless, this something-for-something rule is an obstacle for the mutual trade, because it blocks certain transactions.

Nevertheless, it is sometimes said, that in durable relations the fences between the six outcomes become somewhat permeable. Note, that in the model of Frijters many transactions become possible precisely due to the one-sided love or dedication. It satisfies the need for a social identity14. Incidentally, this love is empathically a group phenomenon. A weaker form of love is also observed in loose networks, among others in the need for procedural justice or fairness (p.104 and further in Pg). People want to be treated with dignity and respect15.

Is the social psychology compatible with the rational choice paradigm? The cognition xji is actually rather dynamical, partly due to the influence of the environment. Transactions lead to a certain structure of the network. Thus many channels between actors are severed. However, nowadays this will result less often in the rigid structure of the Weberian bureaucracy. There is a variety of principles or norms, that regulate the distribution of outcomes among the actors. However, in general the justice principle of the RCT will dominate the other ones. That holds for the micro level, and certainly for the macro level. In principle the actors will exchange many objects, also incompatible ones. But in general there is a preference to limit the effect of personal emotions. The actors remain rational and reasonable. Apparently the RCT does make sense.