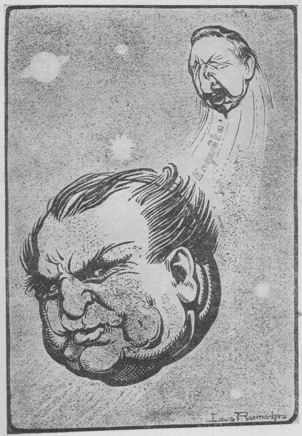

Figure 1: Kuyper and Troelstra

The tail of the comet around the

old globe

He can not hurt me!

Source: L. Raemaekers (Telegraaf)

With the establishment of the European democracy, confessional politics began to organize, and this made it a redoubtable competitor of the social-democracy. The present column describes the principles, that protestant leaders have formulated for their political parties. After a general introduction, the ideas of two early politicians are analyzed, namely those of Abraham Kuyper and Jan Slotemaker de Bruine. Here the emphasis is placed on their proposals for the social policy, which particularly in their times attracted much attention.

In the past years, the Gazette has analyzed the social-democracy in many columns. The evaluation has been extensive, with attention for the political, economic, and moral profile of the social-democracy. Your columnist had to conclude, painfully surprised, that the end judgement about the social-democratic proposals is mainly negative. In the nineteenth century the social-democracy emerged as a movement, which again and again develops new ideas and goals. But none of them can stand the test of criticism. The socialization of the industries, the central planning, and the Keynesian control of the investments are all three plainly detrimental, at least in the extreme and doctrinal variant, that is preferred by the social-democracy.

In restrospect it is rather shocking, that nonetheless at times the ventures of the social-democracy could count on support of a third of the electorat. This is certainly true for the sixties and seventies of the twentieth century, when her ideology began to take on utopian forms. Nevertheless, the ideological failure was bound to occur. But in the nineties the movement has risen from its ashes in an impressive manner, thanks to the ideology of the radical centre, and in many states it has contributed to a period of prosperity. However, it must be acknowledged, that this paradigm has little resemblance with the traditional social-democracy. Besides, the question rises, whether the traditional parties are capable of maintaining the new course. For instance in the first decade of the 21-th century the parties in the Netherlands and in England have again shifted appreciably to the left1.

Since the social-democracy performs so poorly, the attention naturally shifts to other ideological currents. At the end of the nineteenth century the religious leaders begin to realize, that progress is only possible, when next to the people's morals also the material situation of the people is improved. This new idea begins already in the eighties. Note that at the time the socialist movement barely exists. So it is wrong to believe, that the social question has been placed on the agenda by the socialists. Even in England the social action emerges mainly in bourgeois circles, such as the Fabian society. Then socialism is established merely in Germany, thanks to ideological leaders such as Ferdinand Lassalle, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, August Bebel, and Wilhelm Liebknecht. But even there, in the beginning the bourgeois Historical School is at least as important as the socialists2.

The roman-catholic pillar has undoubtedly strongly affected the Dutch labour movement. However, your columnist has little insight in the roman-catholic confession, with all its paradigms and international relations. The protestant pillar is significantly easier to access, partly because it is so embedded in the Dutch history. Moreover, the protestant confession is fairly free from dogma's, so that she can contribute to the social pluralism. Therefore, now the protestant profile will be studied. Strictly speaking this requires knowledge of the theology, which is not readily available for your columnist. Therefore the theological debate will be avoided, if possible, and all attention is focussed on the opinions of leading protestant leaders. These are notably Abraham Kuyper and J.R. Slotemaker de Bruine. Preceding this discussion a short general introduction will be presented.

About twenty years ago your columnist read Van de pastorie naar het torentje, a volume of contributions to a congress about the history of confessional politics3. Although the authors had not altogether abandoned the spirit of the New Left, which had raged a quarter of a century before, the book is sufficiently interesting for serving as the prime source of information for this paragraph. In fact the European Christianity already fell into decay since, say, the second half of the eighteenth century. The tipping point is the French Revolution, which leads to a rapid spread of modernism. The last remnants of the corporatist medieval organisation are removed, such as the guilds. In France the catholic church even loses her possessions, her material basis of power.

During the first half of the nineteenth century the christians follow a wait-and-see policy with regard to the social developments. Then the modernism is still embodied by the liberals. However, in the second half of the nineteenth century the discontent among the christians increases. It is not exactly clear what is the cause. After the reforms of 1848 they were undoubtedly worried about the affection of various traditional rights. Perhaps they also became irritated by the social chaos, and they tried to find binding morals. In the decades after 1848 the social-democracy gradually emerges, and asks for a solution of the social question. She propagates the emancipation of the workers, united in the proletariat. Thus modernism really starts to become a threat to the christian bourgeoisie. Remember the Commune of Paris in 1870, as well as the strong German social-democrats4.

In the Netherlands the constitutional reform of 1848 has given equal rights to the roman-catholics. The Dutch Protestant Church is no longer the state church. Although around 1850 the population is still mainly religious, the conviction is already wavering. The ruling liberals are roman-catholics or liberal protestants. The conservative nobility is protestant, but not very Calvinistic. Abraham Kuyper wants to reinforce the calvinist orthodoxy, and strives for the rechristianization of the population5. He derives from the protestant paradigm the principle of the sovereignty within the personal circle. That is to say, the state must abstain from interfering in the social sphere, as far as a private control is possible. For Kuyper at least the discontent is clear: He believes that liberalism is unnatural, because it lacks the social-organic life.

The roman-catholic church has a similar paradigm, namely the principle of subsidiarity. Private bodies with christian morals are preferred. It is true that the roman-catholic bourgeoisie likes liberalism, but that is not true for its proletariat. Due to the mixed composition of the roman-catholic believers (bourgeoisie and workers) this church is indeed in a difficult situation. It must try to reconcile the classes. This has led to famous papal encyclical letters, notably Rerum Novarum6. This problem is less severe for the protestants, who are the subject of this column. The spirit of the time does motivate them in 1891 to organize a christian social congress. Nevertheless, many workers join the socialist camp. Already during the Interbellum a significant part (15%) of the population has left the church7.

The confessional organizations are actually intended to be ideological centres, which can spread Christianity. They are the figureheads in an expansive strategy. The christians must become an avant-garde, a picked body of men. Kuyper calls this the antithesis, namely the christian reply to the liberal thesis of modernization. Therefore the religious revival begins with the school struggle, where the confessionals demand the same treatment of the special (religious) schools as the state education. The education is obviously a powerful means for the (re-)christianization. According to Kuyper the whole society is amenable to Calvinism, because the devine grace is general. Moreover, the sovereignty within the personal circle implies pluralism. So Kuyper does not advocate the state church. He believes that the state is neutral.

In 1879 Kuyper founds the Anti-revolutionary party (ARP). She is the first Dutch party with a modern structure, including local sections. Then the suffrage is still reserved for the bourgeoisie, including the small entrepreneurs. The ARP actually also opposes conservatism, because she propagates the universal suffrage, at least for bread-winners. Nevertheless, the unchained liberalism can not be halted. The christians do not succeed in their re-christianization, but they must entrench and isolate within their own pillar. Thus in practice the christian organizations mainly become bulwarks of protection. Besides, the rise of socialism, which its revolutionary dogma of the class struggle, changes the entire political spectrum. Religion is not very materialistic. The ARP takes on a conservative role. The protestant pillar has also later never formed a strong labour movement.

This holds even more for the Christian Historical Union (CHU), which is founded in 1908. Her executive consists mainly of conservatives and intellectuals. Originally she does demand the return of the state church, and distances herself from the roman-catholic politicians. On the other hand, she rejects the antithesis8. It is strange, that although it is true that liberalism triumphs, the liberal parties stagnate. Notably the liberal politicians dislike collective organizations, such as trade unions. And these can not be halted either. The confessional and socialist pillars begin to dominate politics. In the Interbellum the political executives of the ARP and the CHU are already replaced. The new politicians originate more often from the organizations, that together form the pillar. Those organizations have much power, becasue they take care of the execution of the political policies.

A problem for the confessionals and especially the protestants is, that the formation of organizations does not proceed spontaneously. Much change is dictated centrally by means of constitutional adaptations. The protestants dislike central coercion, and distance themselves from corporatism. According to them the organizations must be free and autonomous associations9. In any case, during the Interbellum the ARP under Colijn rejects the structural creation of organizations, so that in fact her policy becomes liberal. That undermines the antithesis. The liberal course of the ARP also explains, why after the Second Worldwar the roman-red coalitions will be formed. But only during the sixties of the twentieth century the pillars will collapse. Or more precisely: the parochial political culture disappears10.

Your columnist consults for this paragraph the books Het Calvinisme and Het sociale vraagstuk en de Christelijke religie, both by Abraham Kuyper11. The consultation of these two books is obviously insufficient for completely understanding the views of Abraham Kuyper. It is more a combined review of books. The depth is missing, that does permeate the previous Gazette articles about Kuyper's contemporary P.J. Troelstra. Furthermore, Kuyper often cites the Bible. Your columnist tries to ignore the theological foundation, that Kuyper lays underneath his social views. Interpretations of the Bible are personal, and therefore hardly offer a sound underpinning of policy formulations.

According to Kuyper, since the French Revolution of 1789 the society has developed in an unsound direction. The image of man of this so-called modernism has emerged from the Enlightenment. Following for instance Emile Rousseau it states, that man by nature is inclined towards the good. On the other hand, the Calvinism of Kuyper believes, that man has an open mind for all kinds of sinful temptations. Therefore, man must be embedded in a group, that propagates sound morals, and imposes them, if necessary. Morals pose the norm. However, Kuyper believes, that obeying the morals is abnormal for humans. Precisely their egocentrism inexorably requires the obedience to the eternal collective morals12. In essence he embraces the meritocracy, as long as the elite is guided by the motive of servitude.

Incidentally this does not imply, that humans must follow the orders of their superiors. Only morals themselves are coercive, and thus obedience is a matter of the individual conscience. Morals lead to a sense of duty, and prevent that the personal behaviour degenerates into pride. Here Calvinism also opposes modernism, because the latter adheres to the optimistic conviction, that society can be formed at will. Kuyper objects, that a natural order exists, which can not be broken unpunished. Therefore he rejects the change by means of revolutions, and prefers a harmonious development along the path of gradualness. This is called the cumulation principle. There exists a unique and objective truth. The cosmos has an inner cohesion. Man is amenable to this harmony, because he is by nature a moral being13.

Calvinism allows pluralism. Thanks to diversity, society can prosper. This is also apparent from protestant states, such as the Netherlands, England, and the United States of America. For instance, Kuyper advocates a free science. But his attitude is also somewhat ambiguous. For, he does reject modern science, due to its weak morals, and therefore has founded the Free University in Amsterdam. Apparently he can not accept education by the state. Within the various directions and groups, discipline is allowed. The various groups mutually compete in the preaching of the truth. Here Kuyper distinguishes between three spheres: the society, the state, and the church. This deviates from the normal sociological scheme, which on the one hand includes the church in society, and on the other hand separates the economy from society.

All the various groups form the organs, as it were, of the (social) body. The ideal is an organic global empire, preferably an global patriarchal hierarchy, just like the family. Due to the human weakness, that has not yet been realized (in the times of Kuyper), so that the national state is the highest organ. Since the state organs act according to the service motive, the citizens must accept, in reason, their authority. Although this sounds logical, it is more strict than modernism, which explains the relation between the citizen and the state by the enlightened self-interest. Kuyper acknowledges that the democratic representation is desirable, as long as the situation allows it. The democracy must not end in the people's sovereignty, because any break of the eternal collective morals is unacceptable. For instance, for Russia he believes that the democracy is inconceivable14.

The formation of an organic society also guarantees the general cohesion. For, as soon as the administration is just, the citizens will be guided by their sense of duty. Each of the groups or organs can claim the right of the sovereignty within the personal circle. This is a civil freedom. It is true that the state is indispensable due to the human weakness, but apart from this its task is minimal. Kuyper even calls the state mechanical, instead of organic. Thanks to the constitution the power of the state is bounded. So there is no state sovereignty, such as in fascism. The autonomous circles include the individual, the family, the municipality, and corporations. This also holds for churches, and thus implies the freedom of religion. The state mediates between the circles. Thus Kuyper likes a corporatist suffrage, for instance in productive bodies. The state is neutral.

Thus the state guarantees the right of free expression. In principle the freedom holds only for the personal circle. The domain of the church is the particular grace of its members. In the same manner art is free within its own domain, although Calvinism (or Kuyper) dislikes some forms of theatre and dancing. Here the state weighs the various interests, because it does punish blasphemy, polygamy (less obvious, according to your columnist) and the like. Such interventions are justified for protecting the eternal collective morals. It is obvious that Kuyper is worried about the waning influence of the church, but such fears are common for all ideologists.

In both books Kuyper does not display a clear view on the economic conflicts. He does accept social reforms. He evidently criticizes the excessive accumulation of wealth for some. For, the collective morals must be served, and not greed. But the poor also make mistakes, among others by excessive drinking. It is logical, that Kuyper sees as the solution mainly the moral formation, because the discontent partly originates from hedonistic needs15. Kuyper acknowledges, that the proletariat is exploited economically. He proposes as the solution for instance the establishment of a fair minimum-wage, and the Sunday rest. But this partly concerns relative poverty, due to the preference drift, which is psychical. The material improvement of life is necessary, but its priority is secondary. Happiness is caused mainly by spiritual life.

Rather surprisingly, Kuyper calls the Calvinists the true socialists. For, each group is indispensable for the living human organism. In an organic society, property can not be absolute, as the liberals claim. Property is merely stewardship. As far as property is distributed unevenly, emigration may be a solution. For, large parts of the earth are still not exploited. For this reason Kuyper also justifies the colonization. It turns out that popular concentrations undermine the eternal morals. Kuyper dislikes material support by the state, because it stifles the private initiatives. The factor labour must emancipate by self-organization. Here his organic ideas can again be recognized. However, the state can contribute by means of stimulating legislation. Kuyper notably advocates the extension of the labour laws. Your columnist believes that this policy is poor, much ado about nothing.

In conclusion, your columnist believes that the social system of Kuyper has attractive aspects and is worth considering. It is more stable than the system of the SDAP under Troelstra, which counts on the hostility of the class struggle. And thanks to its desire for pluralism and competition, the Calvinist system is more productive than the roman-catholic aim of corporatism. However, it also has weaknesses. Firstly, there is the rather rigid blueprint for the macro level, which is insufficiently open for social developments. The blueprint even includes the creation of the new man, a precarious undertaking, which is even by Kuyper himself called a miracle. Modern liberalism with its micro approach is more flexible, and more tolerant for chaos. Kuyper is aware of this, but yet believes that strength requires a strict collective dogma.

Besides, there are practical objections. The belief in the eternal collective morals can easily lead to the oppression of minorities, despite the respect for pluralism. The same danger threatens due to the appreciation for the patriarchat. And many social groups will not be able to unite in organic associations. Thus they do not dispose of a protection of their interests. Then the lacuna must be filled in another manner, for instance by means of the service motive or the state. However, the service motive is less strong than Kuyper would like. And Calvinism wants to avoid state interventions, wherever possible. Indeed the ARP cabinets of both Kuyper and Colijn did not excel in their social policies.

The actual interventions of Kuyper even rather contradict the discussed arguments. That concerns notably his actions as the prime minister during the general strike of 1903 16. The confessional cabinet Kuyper hardly attempts to solve the situation in a peaceful manner, and wants to end the strike by means of violence. The strike of the railway personnel is called a crime. Besides the social-democrats, it are mainly the liberals, that try to realize a compromise17. The liberals propose an inquiry into the situation of the railway personnel, before deciding to criminate the strikes. Kuyper rejects their proposal. However, the criminal laws are tempered somewhat, and then the liberals accept them18. The strike rapidly falters, and subsequently the railway companies fire thousands of workers.

The general strike of 1903 illustrates in a painful manner, that the freedom, which Kuyper advocates, is actually limited. Many may have believed, that within the branch-organizations such as the railways the right of sovereignty in the personal circle would hold. For, Kuyper even explicitely propagates organic initiatives. Therefore the state should have acted as a mediator. However, when Kuyper as a prime minister disposed of the power of state violence, he used it with little restraint. The labour movement is not acknowledged as a legitimate organ. Suddenly the paradigm becomes quite flexible. The patriarch ignores the service motive and the eternal collective morals. This is undeniably a significant injury of Kuyper's credibility. That is regrettable, and strengthens the socially conservative image of the churches.

The preceding paragraph creates the impression, that Kuyper does not give the highest priority to the well-being of the proletariat. Here it must be realized, that he (born in 1837) has amply passed his middle age, when writing these two books. In fact most of his life lies in the nineteenth century. That explains why the violent revolutions are his main concern. The idea of social security does not fit in his way of life. The person of the present paragraph, Jan R. Slotemaker de Bruine, does show concern for this theme. He has presented his ideas in the monumental work Christelijk sociale studiën, and the following is based on these volumes19. Slotemaker de Bruine is originally a clergyman, just like Kuyper, but from a later generation (born in 1869). He gets involved in the christian trade union movement, and besides since 1908 is a university teacher.

When in 1886 a part of the churches, led by Kuyper, secedes from the Dutch Protestant Church, Slotemaker de Bruine does not join them. He dislikes the orthodoxy and austere teaching of Kuyper. Therefore he does not support the antithesis. The contents of Christelijk sociale studiën displays reflection and nuances, although in the end Slotemaker de Bruine does always follow the then common standpoints of protestantism. The core of his argument is, that the christian belief must study the social question. The material and spiritual lives can not be separated. Consider health, poor housing, and the quantity of leisure time. Slotemaker de Bruine (henceforth in short SdB) believes that the churches have insufficiently resisted the social abuses. In this respect he defends an avant garde position.

Nevertheless, SdB is definitely not a socialist. The proletariat has its own mistakes, such as perverse pleasures, prodigality and drinking. The failure is both personal and social. Only a healthy social spirit will create sufficient support for reforms. The private organizations are the main driving forces. Therefore solutions require patience, care, and pragmatism. The legislation and the trade union movement do already bring improvements in the lives of the workers. On the other hand, SdB acknowledges that a moral education and formation are indispensable, also for workers. As long as jealousy is unbounded, no reform will create contentment. Everybody must dispose of a certain sense of duty. Here the reader recognizes the politics of the radical centre, which wants to equilibrate the rights and duties. Already then. SdV translates this moral attitude into the concept of fraternity20.

Nevertheless, man is first of all an individual. For, respect and human dignity are coupled to the unique person. Just like Kuyper, SdB states that man is a moral and even religious being21. Norms and values are formed by learning by experience. Knowledge and science must be practised in freedom. SdB rejects the socialist class struggle, and in particular marxism, which considers science purely as an ideological weapon. He does acknowledge, that people can not simply abandon their ideals and social views. But one must be aware of this. Only then pluralism can be realized. It is obvious that morals also determine the system of the state. For, morals guide the actions 22.

For instance, liberalism propagates the abstention by the state. But according to SdB a pessimistic image of man is more realistic, because of sinfulness. And then the state intervention is sometimes inevitable, in order to curb the individual power. It is true that man must be free, but that is only possible by means of commitments. Freedom and bonding are indispensable antipoles. Incessant perseverance can significantly improve society. It must also be realized, that some aspects fall beyond the human influence. In those cases only acquiescence remains23. SdB seems to accept the meritocracy. After this discussion it will be clear, that SdB also advocates a process of change, based on the cumulation principle, that is to say by means of gradual construction, and not by means of revolutions.

SdB publishes his study precisely to stimulate the church in taking social initiatives. The church can shoulder many tasks, for instance with regard to spiritual formation. This must protect the morality, the domain where the church is the leading authority. So here the private initiative does not primarily serve the effectiveness. It concerns the sovereignty in the personal circle. Politics must merely reinforce the social development. He fears that an overly active state will lead to dependent citizens. Therefore he prefers, that the state only intervenes, after the private initiative has failed24. In some situations, such as in the social security, mixed forms of private initiative and state subsidies are most suited. If necessary, the state can develop group policies, because not all are equal.

According to SdB, the organic association of workers in the trade union movement is allowed and even desirable. Workers without their own organisation are economically defenceless25. However, this must not degenerate into a power struggle, wherein the minority is suppressed. Trade unions build on the medieval guilds. One could even consider the establishment of branch organs, on a private basis26. Within this framework, the collective agreement (CAO) is also desirable. In short, in principle the unions must accept the existing capitalist order. Here SdB is not per se more left-wing than Kuyper, but he acknowledges the new reality. In the hearth of the matter, the views of Kuyper and SdB are largely similar27.

Your columnist must conclude, that in essence the argument of Slotemaker de Bruine is sound. In general his views are more valid than those of the then social-democracy of the SDAP. Interesting in his views is also the practical realization. As a university teacher, Slotemaker de Bruine has abstained from doing politics. After the introduction of the universal suffrage in 1917 he changes his mind. Then he joins the CHU, and also becomes a member of parliament for this party. He also undertakes to do various other public functions. He even occupies various posts as a minister, namely of Labour, Social Affairs, and Education. The various sources on the internet are somewhat disappointed about his policies as a minister. It is true that at the time he is already aged, but that can not be an excuse.

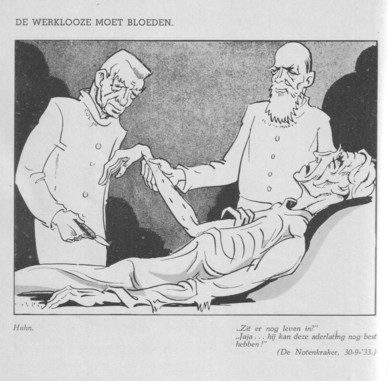

For instance, as the minister of Social Affairs he participates in the liberally minded cabinet Colijn, and then decreases the benefits to the unemployed without protest. And as the minister of education he dismisses woman teachers, as soons as they marry. On the other hand, he introduces the health insurance act. The study of your columnist is not (yet) sufficiently deep for giving his own judgement about the policies of Slotemaker de Bruine. It does become clear, that they can not satisfy the high morals, that he defends in his books. That makes one ponder, because it betrays a created trust28.

The theory of the protestant system looks sound. However, she strongly relies on the natural formation of organs. The idea of collective services, offered by the state, is considered to be unnatural. Unfortunately, the private initiative is less energetic than the paradigm suggests. Pluralism is an obstacle. For, the objective truth is often unclear. The protestant pillar itself has always remained fragmented. One gets the impression that it is liberal, but without the goal of effectiveness. In such a situation the conflict of interests is settled by power. Apparently the private initiative yet needs the encouragement and support of the state - albeit not so coercive as the traditional social-democracy advocates. Therefore the realization of the radical centre remains a challenge for the future. Which party will embrace the challenge?