Figure 1: Coop pin

It turns out that property rights of the production factors affect the incentives to produce. This column analyzes the incentives of the direction in the non-profit organization, the state bureaucracy, and the state enterprise. Also the social ownership in the Leninist paradigm is studied again. The Leninist principles are compared with those of the modern institutionalism. It turns out that in all these cases group morals are a decisive factor.

In a previous column it has been concluded, that the form of ownership affects the effectiveness of economic actions. This is caused among others by the claim on the residue (profit), which the owner has, when his property is used productively. Thanks to the residue the owner has an incentive to organize the production in an effective manner. Therefore the institutionalism develops theories of property rights.

These theories suggest, that an enterprise must preferably be owned by the workers themselves. The mentioned column indeed analyzes the production cooperation. Unfortunately here the problem is, that workers are commonly risk averse. They experience the fluctuating residue as an unattractive source of income. A second problem of the cooperation is, that the shares of the enterprise can not be traded freely. Therefore the value of the shares and of the enterprise remain unknown. Thus an essential external indicator of the functioning of the enterprise is absent1.

The present column will study a number of ownership forms, including constructions, where the enterprise waves the appropriation of a residue. Especially the incentives will be studied, which the workers derive from the construction. Notably the contents of the book The economics of business enterprise by M. Ricketts (in short EBE) has been consulted2.

When an organization trades in some way without the objective of profit, then it belongs to the non-profit sector (see chapter 11 in EBE). Examples are cooperative savings-banks, hospitals, universities, art groups and associations. The non-profit organization (in short NPO) can receive incomes from its costumers. Often such incomes will not cover all costs, and the deficits are compensated by means of donations. The donor is often motivated to give by his personal morals and empathy3. The NPO does not have a clear owner. There is a general board, which supervises the ongoing affairs. The donations do not give property rights. The donor sometimes does get the right of say about the composition of the general board. The law imposes certain obligations, which must be satisfied by the board of an NPO. The daily management is done by the direction.

The NPO has the problem, that the ownership and the payment of profits are absent as incentives for an effective management. In this respect the situation is even more unfavourable than the situation in the mentioned production cooperations. Thus the question is, how notably the direction, as the first responsible body for the daily decisions, can be motivated to perform well. Even more than in the production cooperation the incentives must come from the bonding and the morals within the organization. Note that these phenomena can only occur in rather small organizations (p.386). Thanks to bonding there grows a mutual trust and reciprocal obligations. This is a valuable social capital, which the group members receive as a quasi-rent (p.399). The workers of the NPO are indeed often satisfied with a relatively low monetary reward. Thanks to this modesty the production costs are curbed.

Thanks to the bonding and coherence the personnel engages in mutual supervision and group pressure, perhaps reinforced by active volunteers and the donors (p.389, 399). This can be called an economy of honour, where the direction participates in an immaterial tournament and values a good reputation4. Furthermore, the performance of the direction can be measured by her capability to acquire funds and donations (p.387). Nevertheless, the autonomy of the direction in the NPO is large to such an extent, that it is really an autocracy5. At first sight, the bonding is a sympathetic incentive. But the reader may remember the column about social capital, which points to the disadvantages of especially the bonding (closed, strong) relations. In particular, unsound group morals can be repressive. This becomes very clear in the paragraph about the Leninist paradigm, at the end of the present column.

So in general the commercial enterprise with a profit motive must be preferred above the NPO. Yet the NPO has certain advantages, notably when the consumers and costumers are not able to judge the offered product, for instance in its quality (p.388)6. A commercial enterprise could exploit the ignorance of the buyers in order to increase its profit. On the other hand, the high morals of the NPO make it likely, that it will supply a usable product, with a good quality. Note that here the NPO is a solution for the principal-agent problem, with the costumer in the role of principal. Another advantage of the NPO becomes apparent in situations, where the state supplies insufficient public services. Then the NPO can increase the production up to the desired level (p.390). Here the nature of public services makes a commercial enterprise less appropriate.

A mathematical model (not from EBE) can perhaps clarify the problems of the NPO7. Consider an NPO, which offers a quantity Q of its product for a product price p (per piece). Suppose that this production requires production factors L and K, with factor prices pL and pK. Suppose that N production techniques are available, with production functions Q = fn(L, K), where n=1, ..., N. Suppose that the direction receives a wage w, and disposes of a budget B. According to the neoclassical paradigm the optimization problem of the direction is given by

(1a) maximize for all possible n the utility: U = u(L, K, w)

(1b) under the conditions of budget: B = pL×L + pK×K + w,

(1c) and productivity: Q = fn(L, K)

Note that by definition the NPO receives donations D, so that one has B = p×Q + D. The general board of the NPO imposes the parameters w, D, p, and Q (and therefore also B) to the direction. So the product price p does not clear the market, but expresses the morals of the board and the donors. Besides, the factor prices are imposed by the factor markets. The set 1a-c must be understood in such a way, that the direction has a different preference for the factors L and K, which implies a choice of technique. The preference could for instance base on considerations of status, or on personal morals. Then the appreciation of the direction for these two factor does not coincide with their market prices. Suppose for instance that ∂u/∂L > 0 and ∂u/∂K < 0 hold. The direction aims at maximizing L, within the imposed conditions 1b-c. Furthermore one obviously has ∂u/∂w > 0.

Here the reader sees the dilemma of the general board. It would like to trust the direction. However, when the direction itself can determine the quantity of Q, then it will choose a technique n, which is not efficient. It prefers to produce Q with only L, even when pK would be much smaller than pL. Then, due to the decreasing marginal product one has p × ∂Q/∂L < pL, and that is sub-optimal. This forces the board to define the target for Q in such a manner, that it has the maximal feasible level. Unfortunately the board can not judge the feasibility, because it has less information than the direction. Sometimes the yardstick approach is possible, where the board derives its target from excellent NPO's with a similar product. Furthermore, the limiting condition 1b shows, that the direction will always insist with the board on a larger budget B.

Here the direction does clearly not have an incentive to be efficient. It must be enforced by the board. But the board also does not have a strong incentive to strictly supervise the direction. It is for instance conceivable, that the board prefers a well-known name of the NPO over efficiency8. Perhaps this will indeed increase the donations D, but then the waste continues. Other incentives from the private sector, such as a hostile take-over, are also absent. There is a real chance, that the policy of the direction will be economically unsound. Sometimes the supervision must come from outside of the NPO, for instance from consumers or the media. When the general board must fear to get a bad external reputiation, then it has an incentive to supervise more strictly9.

For several centuries the state has controlled its officials by means of the hierarchical model of the bureaucracy. At the beginning of the twentieth century the sociologist Max Weber has praised the bureaucracy for its effectiveness (p.425 in EBE). Later the public choice theory has stated, that the bureaucracy gives the highest priority to its own interests10. This means that the politicians must supervise the bureaucracy in order to serve the general interest (at least as far as the politicians themselves do not also defend their own interest). The model of Niskanen assumes, that this supervision fails completely. In this case the bureaucracy will maximize its utility. Here the consequences will be described in a simple model11. Suppose that the direction of the bureaucracy uses the production Q and its own budget excess π as the control variables. Then its utility function is u(Q, π), with ∂u/∂Q > 0 and ∂u/∂π > 0.

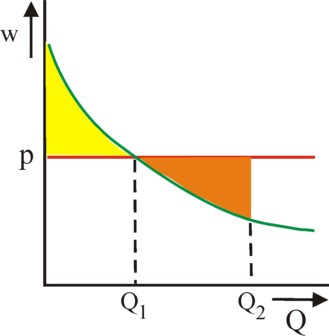

Suppose that the production costs per piece equal p (the make-price), including the transaction costs for supplying the product to the consumers (citizens). However, the supply by means of the market is unsuited for public goods, because they are non-exclusive. In such a situation free riding is threatened. Therefore the politicians must raise a tax per capita τ(Q) in order to finance the public good. In fact they estimate the product demand of the citizens. The citizens attach a piece value of w(q) to the public good, where the marginal value decreases with the supply q (that is to say, ∂w/∂q < 0). The figure 2 depicts the marginal costs and the marginal value, as a function of q. The total value of the public good is TW = ∫0Q w(q) dq for the citizens. When there are N citizens, then the yield of the taxes is N×τ, which must equal the total value. The direction has an "excess" π = N×τ − p×Q, and takes care that this will never be a loss.

Now the optimization problem of the directie is given by

(2a) maximize for all possible Q the utility: U = u(Q, π(Q))

(2b) under the condition of a non-negative budget surplus: π = N×τ(Q) − p×Q ≥ 0

This problem is solved here for two extreme cases. First, suppose that U = u(π). The direction ignores the size of the production, and maximizes its own surplus. The optimization requires w(q) = p 12. The optimal point is Q1, and the surplus π is the yellow area in the figure 2. The costs p nowhere exceed the marginal value, so that the allocation of the used means of production is efficient. But the citizens pay too much, because the supply is not at cost-price13. The budgeted sum is not expended completely, and π remains. The direction has undoubtedly a solution for this. In fact the politicians want to return π to the citizens. However, they do not know the cost structure, and therefore can not supervise adequately.

In the second case one has U = u(Q). The direction maximizes the size of the production. The budgeted sum is expended completely on production, so that π=0 holds. The optimum is Q2. The surplus in the production until Q1 is used to compensate the deficit in the production between Q1 and Q2. In the figure 2 the surface of the yellow area is equal to the orange area. The citizens get value for their tax money. However, in this sitation there is over-production, because the make-price exceeds the value w(q) of the last supplied product units.

In reality. without supervision the supply will lie somewhere between Q1 and Q2, because the direction values both Q and π. It is difficult to introduce positive incentives in the bureaucracy (p.402 and further in EBE). It does not make a profit, such as commercial enterprises, and also does not have personal morals, such as the NPO. Only supervision will work. The politicians must measure the production of the bureaucracy by means of indicators. But indicators simplify reality, and will never measure all aspects of the production. The consequence is, that the bureaucracy will neglect the unobservable aspects of the production. Thus the general interest is yet again undermined.

The state enterprise is capable of executing many different tasks, varying from policy development to -execution. The state enterprise is a particular case of the state bureaucracy, because it generates a concretely defined product. Now the state must make two choices. First, it must decide, whether the supply (the quantity Q of products) can be regulated by means of the market equilibrium. This is only possible for the case of exclusiveness. Here the state must also consider, whether the production can lead to negative external effects. State intervention is partly a choice of morals. Suppose that the state wants to determine the supply Q by itself. Then, the next decision is, whether it will realize the production by itself. For, some of these products can also be produced by a commercial enterprise. This is called a decision by the state of make-or-buy.

During the period 1945-1980 the production by the state itself was popular, because then the production can take into account the general interest. This is an advantage with respect to the commercial enterprise, which is purely profit-driven14. The choice for state production is called the public interest approach (p.433 and further in EBE). The underlying idea is, that the state as a benevolent dictator can objectively determine the general interest. Leninism has indeed imposed such a dictature in a consequent manner. See further in this column. As long as the democratic institutions function reasonably well, an equilibrium of power will form, which is at least a rough approximation of the general interest. However, even in the west this sometimes fails, such as during the seventies of the last century15.

Notably the natural monopolies are candidates for nationalization (p.486). A monopoly is natural, when the marginal production costs MC fall, according as more is produced (∂MC/∂Q < 0). She has an advantage of scale. Many branches, such as the public utilities, transport, telecommunication and the mining of raw materials were acquired by the state (p.453). Such an economy is called mixed (p.454). The public interest also includes the coordination and mutual attuning of the economical activities (p.425). It was hoped that central planning would reduce the total production costs (p.454). Moreover, during the seventies the state was prepated to reorganize the big industries in the private sector, if necessary. The public interest approach was the basis for the Dutch attempts to establish public branch organizations.

According to the public interest approach, the state enterprise must equilibrate demand and supply for its product. This means that the marginal production costs MC must equal the marginal social value MW of the product. However, this theory ignores various disturbing factors, such as the principal-agent problem, incomplete information, and the transaction costs. The direction of the state enterprise is in a comfortable position, because she disposes of more information (p.458). Supervising the direction is difficult, because the production process is complex. There is rarely a clearly observable relation between the production costs and the supplied products. Then the politicians must evaluate the result by means of deficient indicators, which can be a moral hazard for the direction. Moreover, the freedom of the direction must not be curbed too much (p.458)16.

Therefore the politicians are well advised to appoint a competent direction (p.440). But the direction members in the public sector can hardly build up a good reputation, because their tasks are so complicated. In the private sector, the direction can simply prove its quality by making huge profits (p.465). Thus the public sector must select its directions by means of political and bureaucratic procedures, which offer little guarantee for an effective operational management (p.441). Such a direction does not need to fear, that it will be punished by the share-holders. Her enterprise can not even fail. Besides, even a competent direction is not able to serve the public interest. The equality MC=MW can not be realized, because the social value W is too vague as a concept (p.438, 442). Therefore directions were in practice rarely able to apply the rule MC=MW (p.442).

After 1980 the public interest approach becomes controversial. The experiences with the state enterprises are unsatisfactory, and credible theories have been proposed for explaining this. For instance, the fear for natural monopolies has decreased. For, thanks to the economical dynamics there are continuously new products and production methods, which are a threat for the existing monopolies (p.487). This counteracts the concentration of power. A private monopoly, which raises its product prices too much, must fear that a competitor will enter his market17.

Since central planning has failed, the politicians again see the advantages of free markets, notably as an instrument to stimulate the directions of the enterprises. The state can supply public services by concluding contracts with enterprises. In the decades after 1980 many state enterprises are (again) privatized. Scientific studies show, that privatizations can indeed be an improvement, with regard to effectiveness, profit, paid dividends, and sales (p.482)18.

The Gazette has regularly paid attention to various Leninist economists, in order to understand this curious ideology. Here this will happen once more, because the Leninist paradigm (in short LP) is in essence a theory of property rights. Thus it is a variant of institutionalism. Moreover, the LP has been tried amply in practice. A warning in advance is justified. All those economists carefully conform to the party line, albeit sometimes reluctantly. That was better for their health. The Leninist paradigm is more a credence than a logical model, and assumes an absolute truth. Therefore the economists argue like priests. The debate must be limited to niggling. That is not a pleasure to read. And since the credence is unsound in its core, the focus on details makes no sense.

Nevertheless, the LP has apparent similarities with modern economics, especially with new institutional economics (in short NIE). The present paragraph sums up the similarities and analyzes the deviations. The hallmark of the LP and the NIE is the study of institutions. Here the NIE places the height of the transaction costs at the centre of the analysis. Although the transaction costs are also important for the LP, it notably focuses on the social exploitation. In this respect it is related to the theory of social capital. The NIE consists roughly of two currents. The first one, which is attached to the name of Oliver Williamson, analyzes contracts. The starting point is the subjective optimization of the individual utility. The second, which is attached to Douglas North, analyzes the social evolution. This is called the radical approach19. The LP belongs to the second category.

The radical approach places the institutions in a historical context, for instance primitive tribes, feudalism, capitalism, or socialism (or Leninism). The LP calls this historical materialism. The social dynamics is emphasized, more than in the contract-directed approach. Groups and organizations are necessary in order to survive under the continuous change20. So the radical approach studies the evolution of institutions. The hallmark of the LP is the huge importance, that is attributed to the institutional form of property rights, notably with respect to the means of production. Capitalism is based on private property. In socialism all means of production become the property of the state. This is called social ownership. The LP assumes, that the form of ownership fundamentally affects the social relations.

For, the control of the means of production gives the right to appropriate the residue (the surplus value) in the production process. Thus the LP is materialistic. For this reason it presents itself as an objective theory. The society obeys objective laws21. Besides, materialism implies that the individual is mentally programmed by his own circles22. In this respect the LP is unmistakably communitarian. Phenomena are studied at the macro level. There are just two types of consciousness, namely of the owners and of the dispossessed. The class is the individual point of reference. The LP defends the controversial hypothesis, that the class of the dispossessed workers is exploited23. This notion slowly penetrates into its conscience. Therefore the LP is a conflict theory. Since the dispossessed form an overwhelming majority, their class morals must become leading in the social reforms.

On the other hand, in the NIE the morals affect the development independently, also in the radical approach of North. The morals do not originate naturally from matter. The individuals maximize their own utility, and this can be realized in an immaterial manner, when desired. The NIE is based on the methodological individualism and is subjective. It commonly interprets society as a system in dynamic equilibrium, where the conflicts are at the micro level. Individuals and groups can survive by imitating each others' behaviour. Circles develop routines, norms and roles. Individuals refer to their own circle, and can change it by means of innovative actions24. See the learning model of Kolb. The different view on the freedom of the will has important consequences. For instance, the LP couples crime to the form of ownership, and thus belittles the personal responsibility25. The NIE couples crime to circles, and perhaps to genetics.

According to the NIE and the LP, the social evolution can lead to a historical selection of the most efficient economic systems. They will oust the less productive systems. In this sense the NIE and the LP both contain an element of determinism. Incidentally, North believes, that this tendency is often thwarted by incidents26. The LP states, that socialism creates the best conceivable conditions for the production, and therefore it will surpass capitalism, and succeed it. The LP justifies this claim with another hypothesis of the NIE, namely the principal-agent model. Such models search for incentives, which increase the effort of the agent, and thus merge the interests of the agent and the principal. According to the LP state ownership is such an incentive. Thanks to state ownership, the worker is no longer exploited, like in capitalism. Under the socialist regime the interests of the worker and society coincide27.

For, the worker emancipates in and by the society. The social development can take its natural course, because the people choose their own future in the plan. Thanks to the organization the dynamics can be controlled. Therefore the LP is primarily a theory of existential security. The evolution pushes in the direction of cooperation. Remember, that Leninism has been formulated in a time, when the famous sociologist Max Weber still praised the bureaucracy28. The transition to state property is radical to such an extent, that it must be realized by force. The reader will probably find this a risky experiment, because the predicted harmony is merely a hypothesis. After the transition there is perhaps no longer a way back. North calls this an accidental factor: a coup d'état can lead the evolution into a blind alley29. It is better to reform stepwise.

In the LP the predicted high productivity of state property is more an extra than a goal. Thanks to the social capital the transaction costs will fall. This is attributed to the cooperation in the economic planning, which can eliminate various economic abuses. Therefore the LP predicts an accelerated growth. Besides, the state, or actually the central planing agency, designs the plan in such a manner, that the free unfolding of all workers is insured30. The reader may think that this is a contradiction. For, when the planning agency fixed the free space of the individual worker in advance, then there can be no longer an autonomous and free individual unfolding. The relation between the state and the individual is actually paternalistic. Anyway, in fact there are two hypotheses: (a) the social ownership eliminates the exploitation, and (b) in this way the individual productivity will unfold fully.

Conformable to the principal-agent model, the LP assumes two types of incentives, material and moral ones. The moral incentives are by far the most important. Since the class as a whole experiences the moral incentives, they are also material, albeit indirectly31. The moral incentives are internalized. In socialism they stimulate a voluntary effort, because there labour is a pleasure and a joy. This is naturally merely a hypothesis and a belief, but in the LP it becomes the absolute truth. Such an optimism is present in all socialist movements. The loyal reader will undoubtedly remember the scheme of the Flemish social-democrat H. de Man, who analyzes the causes of job pleasure and discontent. According to him the causes are in the task itself, in the organization and in society. The modern theory points to immaterial motives of workers, such as the performance and the mutual contact, but rejects social motives.

In the scheme of the LP, the social system determines all causes of job pleasure and discontent, at least in the last resort32. Thanks to socialism, the agents are incited positively. Only the social production is objective. The difficult search of the NIE to invent self-enforcing contracts and clever ways of supervision are unnecessary, and also useless, because the capitalist exploitation will stifle all enthusiasm. In other words, it is true that there are functional and organizational causes of pleasure in capitalism, but they are distorted by the capitalist system. The Leninist state reinforces the moral incentives by means of an energetic and encompassing guidance (propaganda). The LP is convinced, that thanks to its economic order the human behaviour will improve. There will even emerge a Leninist man, the socialist personality33.

Doubt has just been expressed concerning the hypothesis of the LP, that exploitation is absent in the socialist form of ownership. The Leninist economists expect that their command-economy will not be thwarted, although here yet the workers are pressurized to do their plan-task. Even the company managers themselves can not act freely. The LP trusts, that the workers will serve the general interest, if necessary incited by means of propaganda34. The coercion is somewhat moderated by giving a say to the workers, at least to the Leninist trade unions. Besides, there are investments in the working conditions and in the atmosphere in the workplace.

During the sixties of the last century, the Leninist states began to realize, that material incentives are indispensable for making the production effective35. Now, socialism by nature indeed gives a material incentive, because it (supposedly) increases the production. However, the contribution of the individual worker to this success is minimal. Therefore the worker is tempted to be idle, and to free ride on the efforts of others, as it were. Therefore, also Leninism must use concrete monetary incentives, such as the salary and performance-related premiums. The organization creates tournaments, as it were. Competition is important, although it is sometimes moderated by means of collective premiums instead of individual ones. Also, the material incentives are always combined with moral ones, wherever possible, such as the presentation of deeds, or an honourable mention in the company paper.

Thus one could hope, that the workers are compensated materially by the command economy. However, the LP introduces yet a second source of exploitation, namely the so-called dictature of the proletariat. The advantages of the social production become only clear, when the majority of the workers have changed into socialist personalities. During the transition time to this new type of consciousness the state must rule as a benevolent dictator. The LP assumes, that the workers will support the dictature. The dictate is directed against other groups, such as the owners, farmers, shopkeepers and small entrepreneurs, intellectuals etcetera. Thanks to the dictature a new order will develop, which offers the proletariat and the other groups optimal opportunities for unfolding. The false consciousness of the owners dies. This is the Leninist dream36.

Since the dictature infringes on the human rights, it is worth analyzing its justification in the LP. A good source of information is Einführung in die Marxistisch-Leninistische Staats- und Rechtslehre (in short SR)37. The socialist dictature is justified by its elimination of the exploitation, which supposedly occurs in capitalism (p.59 in SR). The LP believes that it has been proved, that socialism is the guarantee for human dignity (p.62). Henceforth the society will be harmonious, both nationally and internationally. Socialist states do not mutually make war (p.61). It is acknowledged, that the proletariat is not yet completely converted to the LP. Therefore a dictator is needed, namely the Leninist party (in te GDR this is the SED) (p.62-63, 101). The party is the avant-garde of the working class. The LP is paternalistic, and believes that a pastoral guidance is unavoidable38.

The LP explicitely rejects political pluralism (p.83). The Leninist party has shown, that it supports the LP and propagates it energetically. Therefore it has the best ideological ideas of all parties39. It is the only servant of the general interest. A multi-party system could contain parties, which reject Leninism. Such parties thwart the general emancipation of the population, and therefore are undesirable (p.81). There is even the danger, that they become a mouth-piece of the monopoly-capital40. It is also undesirable to have various Leninist parties. For, such a division will weaken the organization of the workers. This principle is called democratic centralism. Politics, the government and the economy must all be led by a single central actor. Thanks to the party as the dictator, the people act as a unity (p.106, 110, 114).

The political consequence is, that all social groups are subjected to the Leninist party41. This also holds for the trade union federation FDGB, for instance (p.60,64). The civil society as a social capital is put in an ideological strait-jacket. The state must be the instrument for the dictature (p.87, 103). It is the executive apparatus of the policy of the Leninist party (p.88). The party leaders also occupy several essential functions in the state and the council of ministers. The consciousness of the population can be controlled by means of the constitutional law (p.96). A neutral legal system is rejected, because it would protect the private property of the monopoly capital. The socialist state represents the popular will, precisely because it controls the consciousness (p.98). This hypothesis is also the justification for the economic plan targets (p.109).

In short, the reader may observe, that the Leninist paradigm expresses a sectarian political belief. It promotes a regime, which despises opponents, and justifies their brutal repression. The implacability of K. Marx is merged with the mass terror of V.I. Ulianov (alias Lenin). It defends a perverse abuse of power, which stifles the evolution of institutions. Or, if preferred: the LP is indeed the institutionalism of the dictature. Nevertheless, even without the revolutionary component the LP looks primitive. It is hardly credible, that the evolution is completely determined by the material conditions of the production. For, the social morals are an independent factor. Just consider the religion and the regional culture42.

It is also not realistic to reduce the society to two classes, owners and dispossessed. And practical experience has shown, that state ownership eliminates all kinds of productive incentives. And central planning stifles the initiatives and innovations of private individuals and circles. People can not be forced at will into an ideological mould. In practice, the population has experienced the Leninist dictature as a repression and exploitation. Besides, it has turned out that the Leninist system is less productive than the capitalist system. Your columnist concludes, that the LP, and incidentally also many hypotheses of marxism, can easily be discarded. Naturally the practical experiences do remain valuable as a source of information for the analysis of economic incentives (including ownership).