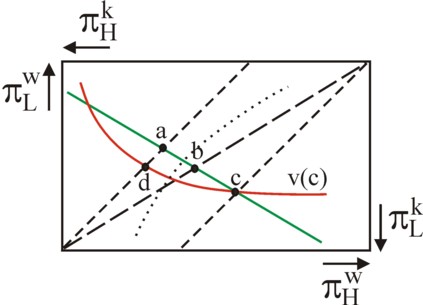

Figure 1: Edgeworth box for risk sharing

with observable effort

The diversity of ownership forms has always fascinated the economists. The present column first describes several principles of property. Next an analysis is presented for three basic forms of ownership within the enterprise. The case of the production cooperation is studied in detail. Finally the social property is studied, such as is present in Leninism. The Leninist enterprise is modelled mathematically.

The Gazette has dedicated various columns to the planned economy with state ownership of the means of production. They describe the experiences and attempts to reform the former Leninist states. Until now a theoretical analysis of the collective property has been missing. Yet there exists already a lot of literature about this theme, and special attention is paid to the productive incentives, which originate from property. The present column is a first attempt to make an inventory of the available knowledge. Here the focus is on the productive enterprise, which is collectively owned by its workers. Strictly speaking this deviates from Leninism, which mainly has state enterprises. On the other hand, the Leninist state is controlled by the working class. Therefore the column yet analyzes both the production cooperation and the Leninist enterprise. Consumer cooperations and the like are (for the moment) not considered.

The ownership gives three rights to the owner1:

The question rises, why the society accepts a property right. This is in essence a philosophical problem, and it has led to an enormous amount of literature. For the present column a few short remarks suffice2. The traditional justification of property is expressed in the seventeenth century by the philosopher John Locke3. He states that everyone has a property right with regard to the products of his own labour. This is a moral view, but it also has a practical justification. For, it is precisely the acquisition of this property, which incites the individuals to make efforts. It appeals to the human greed.

Nowadays the institutional economists search the justification of property mainly in the effectiveness of economic actions. Individuals will use their property in an effective manner, because they want to maximize the residue. Besides the operation of markets is such, that the property is allocated effectively4. For, the concerned good has the highest value for the person, who can produce the largest residue. Thus this individual will acquire the good as the highest bidder. In short, the property right guarantees an optimal allocation of all means of production. Renting or letting out property is a variant of this theme. The tenant or lessee is capable of producing a larger residue with the good than the owner himself.

Furthermore, the ownership as a mechanism of allocation contributes to a just (effective) distribution of the sales of the production. This argument can be explained with the theory of the incomplete labour contract, which has been presented in the recent column about the labour market5. Someone wants to commission the making of a product, and he contracts a worker for this. The client expects, that the product has more value to himself than the agreed price. This extra value is called a quasi-rent. The execution of the commission requires an investment I in tools, or perhaps in training. Now the question is who must make the investment: the client or the worker. This is a matter of ownership. The answer depends on the degree, in which the expense I can be seen as specific costs.

Specific costs are only profitable for a concrete commission, and not for other applications. As soon as someone makes these costs, one has a lock-in: he is financially tied to the commission. This stimulates opportunism of the other party, because he can renegotiate the contract, and can demand a part of the quasi-rent. The actor who invests I will obviously try to avoid such a situation (called hold-up). The possibility of the hold-up at least leads to under-investments. The solution to this dilemma is found in the ownership: the costs for I must be made by the actor, who sees them as not very specific. For, he will not come in a state of lock-in. This is a matter of effectiveness. Thus it seems logical, that the worker (or perhaps his company) buys his own tools. They belong to the profession, and can be used for other commissions. On the other hand, the client can not use them elsewhere.

The structure of ownership depends on the chosen structure of capital6. The entrepreneur can attract capital by issuing shares (and so shared ownership) or by borrowing. The capital supplier runs the risk of non-payment, in all situations. Thus there are three tasks in the enterprise, namely the decision, the supervision of the execution, and the risk management. These tasks are distributed among the participants (workers, direction, capitalists) in such a manner, that the costs of the production are minimal. More generally it can be said, that in legislation the property rights must be formulated in such a manner, that effective actions are stimulated7. The rent seeking must be discouraged, because it is not productive.

Thus one tries to find the socially optimal legislation. This is a dynamical process, because thanks to technological and social progress there continuously emerge new ways of acting8. The existing legislation can be sub-optimal for such actions. Then the benefits of new property laws must be weighed against the costs to realize them. An important source of costs of changing legislation is the undermining of the legal security. It is discouraging, when changes in the legislation continuously undermine the existing order. People want to be able to rely on laws that are sufficiently durable. Besides the rent seeking by interest groups will increase, when the groups can promote changes in legislation with little effort. The costs for the group would be low.

The preceding argument gives the impression, that the enterprise must actually be the property of the workers themselves. Then this is called a cooperation. Here the workers themselves receive the residue of the production. They are strictly speaking the shareholders of their enterprise. It is not absolutely necessary, that they are the sole owner. Anyway, they must probably contract loans from a bank, so that a part of their enterprise must be pledged. It is also conceivable, that the workers attract external capital by issuing extra shares. Then they engage in a partnership with capital. But even in the extreme case, that they sell all of their shares, there reward can still contain a part of the profit. Then the workers yet bear a part of the entrepreneurial risk. This situation is decribed in the column about the Edgeworth box for the principal-agent problem.

Thus there are actually three structures of organization, where the workers bear a risk of income: (a) the normal enterprise, which gives its workers a profit share, (b) the partnership of labour and capital, and (c) the pure cooperation. A model can clarify these three types of organization9. Here the importance of incentives and motivation will also be studied. Suppose that an enterprise operates in such a manner, that the size π of the profit is uncertain. The profit is πL with a probability of pL, or πH with a probability of pH = 1 − pL. Let πL<πH. Suppose there is profit sharing between labour and capital, with in both cases π = πw + πk. The mentioned column has shown, that the Edgeworth box can represent this in a compact way. The figure 1 shows the picture of the box. See the previous column for a detailed explanation, if required.

The workers have the origin of their system of coordinates (πHw, πLw) at the lower left, and the capitalists have the origin of their inverted coordinate system (πHk, πLk) at the upper right. The two lines with an angle of 45o are the certainty lines of the workers and the capitalists. The certainty line of the workers describes enterprises, which merely pay a fixed wage. The workers receive a guaranteed wage w = πHw = πLw. The capitalists bear all the risk of income. The certainty line of the capitalists describes enterprises, which borrow all the capital as credits with a fixed interest k = πHk = πLk. Now the workers bear all the risk. Interesting in the figure 1 is the diagonal line, which runs from the corner leftunder to the corner right above. For, on this line one has πLw/πL = πHw/πH. That is to say, the profit sharing is independent on the size of the profit. Here labour and capital share the risk.

Consider finally the green line in the figure 1. This represents one of the many iso-profit lines for both the workers and the capitalists, obviously for their expected profit E(π), with a slope of -pH/pL. The green line intersects from left to right the two certainty lines and the diagonal in the points a, b and c. These three points correspond precisely to the three mentioned types a, b and c of organization, with each time the same expected profit E(πw) and E(πk). When both the workers and the capitalists are risk neutral, then these three points also give the same expected utility. In this case, on the green line neither the workers, nor the capitalists have any preference for a certain type of organization.

However, the assumption of risk-neutral workers is not very realistic. It is commonly assumed, that the workers are somewhat risk averse. Then in the figure 1 the red curve is an indifference curve of the workers, namely the one through the point c. On this curve their utility v(πHw, πLw) is constant. At the lefthand side of c the isoprofit curve and the indifference curve separate. The indifference curve intersects the certainty line of the workers in the point d. The line piece a-d represents the bargaining room of the workers and the capitalists. In the type a both can improve their situation with respect to those in the point c (or also type b). Apparently in this case of risk-averse workers and risk-neutral capitalists the type a organization is preferred over the types c and b. Here the ownership is not an incentive for the workers. And actually this does not surprise, because in this situation the workers have no freedom of action.

Therefore consider next a situation, where the workers can increase the probability pH of a high profit by making an extra effort Δe. That is to say, pH = pH(e), with ∂pH/∂e > 0. The effort e is a burden, which causes costs c(e) for the worker. Thus his utility function becomes u(π, e) = v(π) − c(e). The worker must consider in each point (πHw, πLw) whether it pays to make the extra effort Δe. The previous column has shown, that thanks to the effort Δe the indifference curves obtain a steeper slope. According to this column a boundary curve can be determined in such a manner, that on this curve the extra effort is profitable for the worker. In the figure 1 it is shown as a dotted curve10. On this curve the worker clearly has a share in the profit, and therefore bears a risk of income. Yet he will prefer this profit sharing instead of a fixed wage w.

The reader sees that apparently the type b of a partnership between labour and capital is possible, although it evidently depends on the aversion of the worker with respect to both the effort (so c(e)) and the risk. Note that the model also takes into account the preferences and limitations of the capitalists. In particular, it is assumed, that the capitalists do not know whether the workers indeed make the effort Δe. The effort is unobservable for them, and therefore can not be enforced. The preference of the capitalists makes it impossible to ever realize the production cooperation (type c). For, then the boundary curve must have an intersection with the certainty line of the capitalists. The capitalists will not accept this situation, because then the normal enterprise (type a) promises more profit11. But the type c can obviously be approximated closely, so that the package of shares of the capitalists is insignificant.

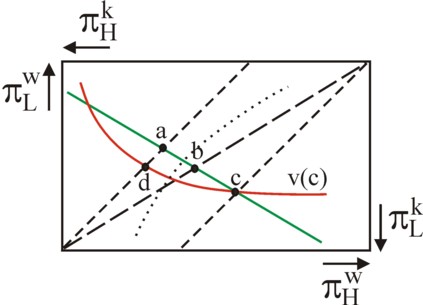

The figure 2 shows such a structure of the organization, where the capitalists both supply a credit and keep shares. Due to the fixed interest rate k, merely a residue π − k can be distributed, so that now the line for profit sharing (π-k)k / (π-k) is flatter. This is the lowest blue line in the figure 2. For completeness, the structure of the organization is also shown, where the workers have a fixed part w in their income (and the capitalists do not). This is the upper blue line. It can be interpreted as a variant of the type b (partnership), where the workers own a package of shares. But it can also be simply profit sharing without ownership, so the type a.

There are many theories about the advantages and disadvantages of the cooperation12. A model has just now been analyzed, where the capitalists are not able to supervise their workers. Then the workers must have an internal motivation for making an effort. This is the case for the cooperation, because the workers share the residue π and thus their effort is indeed profitable. Unfortunately even in the cooperation the dedication of the workers is not perfect. For, often the individual worker will only contribute marginally to the end result, for instance when the cooperation has many workers. Then it becomes attractive for the workers to engage in free riding13.

And some workers will not like the risk of income. As soon as the profit πw temporarily falls, they will try to find work in another enterprise. This is less likely, when the human capital of the worker is specific, for this does not allow for a high wage elsewhere. Note that in a cooperation the workers are willing to invest in themselves. Now this does not cause a lock-in, so that the worker does not have to fear a hold-up. But a problem is, that in the cooperation the profit sharing of the worker ends, as soon as he leaves the enterprise. This can cause short-term behaviour, because finally each worker will retire. Such workers do not want to invest a part of the profit, or to pay off debts. The property of the retired person could be transferred to his pension fund. But a pension fund is not very stable, when it owns just one enterprise.

Even a cooperation must dispose of a direction. The management and the ownership are separated. An advantage of the cooperation is, that the workers are well informed about the state of their enterprise, so that they can control their own direction without much additional transaction-costs. However, a disadvantage of the pure cooperation is, that the shares are not traded on a stock market. In normal enterprises the quotation of the share is an indicator of the performance of the direction. The value (quotation) of the share is determined by means of demand and supply on the stock market. The cooperation misses this instrument. Another means must be found for testing the performance of the direction, for instance the comparison with comparable competitors (ring test). Besides, the direction can profile itself by building up a reputation.

It is also unclear, how the decisions in the cooperation must be made. In principle the direction will make the operational decisions. But it is subordinate to the owners, and these are the workers. Collective decisions are notoriously difficult, and can lead to irrational outcomes. Disagreements can notably emerge, when there are conflicts of interest among the workers. An example: it has just been remarked, that older workers get a short-term horizon, due to their forthcoming retirement. The most effective manner for reducing conflicts and free riding is probably the application of group pressure and social control. Provided that the cohesion (bonding, coherence) is sufficiently strong, the group or circle can impose an order on its members. Here the field of social psychology is entered. The workers develop a value rationality, where norms are internalized and obligations are acknowledged.

The profit sharing in the cooperation is not just an incentive to make an individual effort, but it also stimulates the supervision by means of mutual checking. In this case the group pressure is a form of disciplining, which aims at the maintenance of the group norms. It commonly controls by means of immaterial incentives, such as changes in the individual status, reputation and authority. When the group member i imposes such a sanction or fine vij on the group member j, then the member j will henceforth make a greater effort. One has ∂ej/∂vij > 0. On the other hand, the inspector and attendant i must make costs c(vij). Therefore the inspector must always decide, whether these costs are compensated by the result of the enforced extra effort ej of the group member j. Apparently there is an optimal level of supervision14. This kind of choices can be modelled with game theory.

The preceding arguments make clear, that the production-cooperation must preferably consist of homogeneous workers with a common interest. Heterogeneous cooperations are amenable to conflicts. The number of workers must also remain limited, because a strong cohesion especially requires small groups and circles. Group pressure is most effective, when the groups members personally know each other. They feel a mutual dependence. On the other hand, large enterprises are characterized by anonimity15.

Furthermore, the pure cooperation has just a single external source of capital, namely the credit from the bank. For, the possibility to emit shares on the capital market is absent. However, note that investments with a specific character can not be paid by means of a credit. For, specific capital goods only have value for the application within the enterprise itself, so that they can not serve as a pledge for the credit. The cooperation does have the option to emit freely tradable shares on the financial market. Then the enterprises changes into the type b, the partnership of labour and capital16.

The behaviour of the cooperation on its product market is interesting17. Its profit is given by π×L = η×q − k. In this formula L is the number of workers, η is the unit price of the product, q is the sales of the product, and k represents the costs for the used capital goods (interest rate, redemptions and the like). It is obvious that q depends on L, and in addition on the total stock of capital goods K. For the short term is may be assumed, that K is constant (and thus k also). The workers want to choose L in such a manner, that their individual income π becomes maximal. For this they must solve the equation ∂π/∂L = 0. This yields the identity

(1) ∂q/∂L = (q − k/η) / L = π / η

The lefthand side is the value of the marginal product of labour. The value η × ∂q/∂L of the marginal product equals the individual profit share. Now suppose that the product price η rises due to an increasing demand on the market. Then the value of the marginal product also rises with η, but the value of π rises even faster18. The worker will try to restore the equilibrium condition in the formule 1, namely by reducing L and therefore by increasing ∂q/∂L. Thus the pure cooperation exhibits the perverse reaction, that it will shrink as an enterprise, as soon as its product becomes scarce!19 This does not only hurt the consumers, who now can not sufficiently satisfy their needs, but also the employment!

The former Leninist states used the legal form of the production cooperation, for instance in the form of the Landwirtschaftlicher Produktionsgenossenschaft (in short LPG) and the Produktionsgenossenschaft des Handwerks (in short PGH)20. Nonetheless, the cooperation is really rejected, because it is a remnant of capitalism. In the Leninist doctrine, socialism is equated to the planned economy. The competitive market is fundamentally rejected, because it would lead to unacceptable social losses. The arguments have a long history, and remind of the plea of the SDAP for socialization in the Netherlands:

In the former Leninist states the social property dominates, which in practice results in state property. The state disposes of the state enterprises, and appropriates their production. The right of sale of the property is absent in this system. However, the state is not an autonomous body, but it is subjected to the working class. In the GDR, this class was led by the party (SED) and the trade union movement (FDGB). Thus the workers design their own year plans, via their representative at the central level. This is called democratic centralism. The professional population is both a worker and an owner. Although the private property still exists in the cooperations, these are forced to conclude yearly contracts with the central planning agency. This erodes the right to dispose of property to such an extent, that the cooperation obtains a socialist character21.

The social property is praised as the highest stadium of progress and development. The reader will undoubtedly wonder how that type of property can still have a stimulating effect on the workers. For, it is true that the worker is the owner, but the ownership is diluted to such an extent, that it hardly gives individual rights. This holds in particular for the enterprise, where he works. And the mutual control is impossible in the anonimity of society. Leninism tries to limit free riding by introducing material and immaterial incentives. First, the SED and the FDGB have introduced profit sharing, generally in combination with the individual reward for performance (tournament). So it concerns enterprise of the type a. This appeals to the material interests22.

Second, the SED and the FDGB tried to further the social cohesion, and to spread good labour morals. They aim to form the workers into socialist personalities, say a homo politicus. This requires a large and permanent effort, because of old the population is socialized to have a capitalist conscience, and this is continuously stimulated by the presence of the capitalist west. The private property represses the workers, but yet appeals to human egoism, also of the GDR citizens. The SED and the FDGB become legitimate as leaders, exactly because they most resist the undesirable capitalist imperialism. They undeniably lead a moral movement - somewhat comparable to christianity23. However, they justify their behaviour with the odd looking claim of scientific truth.

It has just been remarked, that the group pressure becomes weaker, according as the group is larger. The modern society is in essence anonimous. Therefore the Leninist regime had to employ draconic instruments, such as the political and economic dictature, as well as a strong censorship and even a restriction of the freedom of movement (at the state borders). The leaders believed that the goal justifies these means24. At the level of the enterprise, brigades and worker's collectives are formed, where the group pressure can have some effect. Whenever possible, a propagandist is a part of the collective. Nevertheless, the regime finally collapsed due to its defects. The Leninist anthropology is simply unsound. The principal-agent problem is ignored, so that the economic waste is larger than in capitalism. And in political regard, it turns out that the human personality is less mouldable than the Leninists hoped.

This paragraph describes a mathematical model of the Leninist enterprise, which is invented by the economist E.G. Furubotn25. It is discussed here, because it shows how the Leninist activities can be presented as a scheme. Besides, it deserves attention as a curiosity. For, after the collapse of Leninism any practical meaning of the model has obviously disappeared. It goes as follows. In the period t the short-term production function of the enterprise is given by q(t) = F(L(t), ap, K). Here L(t) is the number of workers, ap is the labour productivity, and K is the stock of capital goods26. Suppose that K is constant. The direction of the enterprise has for the period t a planned target Q(t), imposed by the central planning agency. The planning agency uses production-normatives, which among others allocate a number of workers N(t) for producing Q.

The direction will receive a premium, when the planned target is exceeded, that is to say, when q(t) > Q(t). Therefore she prefers a low target Q. This gives her an incentive to report a productivity αp to the planning agency, which is less than ap. Thanks to the asymmetry of information the deception is not observed. One simply has Q(t) = Q(αp). The reported αp does need to satisfy N(t) ≥ L(t).

Unfortunately, it often happens in the Leninist system, that the planned production factor N(t) is not completely supplied. Consider various hitches on the labour market, for instance because the schools can not educate sufficient new workers. So the direction must calculate with the expected N(t), namely E(N(t)), instead of N(t). One has E(N(t)) ≤ N(t). The uncertainty forces the direction to by way of precaution form a stock Λ(t) of workers, and in many periods a part of them will be superfluous. The stock assures the "allocation" of L(t). The superfluous workers are engaged in unproductive activities. Thus the continuity equation of the expected stock E(Λ(t)) is given by

(2) E(Λ(t)) = Λ(t-1) + E(N(t)) − L(t)

Thanks to the stock Λ(t-1) the direction obtains some freedom of policy. For, during the period t it can employ at will any number of workers in the production, up to a maximum of Λ(t). Thus it can decide to have any production q(t) between Q(t) and f(Λ(t), ap, K). In this manner it can acquire a premium for this period t. However, the disadvantage of the decision q(t) > Q(t) is, that αp is no longer credible, and the planning agency will equate the next target Q(t+1) to q(t). Therefore the freedom of policy of the direction becomes less, and it is not possible to endlessly earn premiums. Moreover, after each premium more workers must be employed, so that the direction has less and less superfluous workers. In short, there is an exchange between the pleasure of premiums and Λ(t). Apparently, the utility function of the direction is given by U(t) = u(q(t), E(Λ(t)), Q(t)).

Thanks to the preceding argument, the optimization problem of the direction can now be formulated. It is

(3a) maximize for all possible L(t): U(t)

(3b) subject to the conditions of continuity (formula 2) and productivity (q=F)

Apparently this is a single-period optimization, for the period t. However, the presence of Λ(t) in U(t) implies, that the decision in the period t has consequences for all following periods. In fact the system 3a-b is a many-period optimization, where the direction must decide about the distribution of the paid premiums in time. Here the utilities of all periods must be discounted and aggregated. Furubotn does not discuss this.