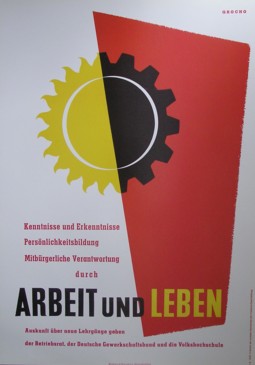

Figure 1: Poster DGB

The industrialization creates so much wealth, that it leads to the welfare state, The welfare state has a large diversity of forms. The present column describes several models, which try to order the diversity. After a general introduction about group behaviour and the policy mix there is a presentation of: the inclusion model, the paradigm of the radical centre, the trust model, and the three-worlds model. Finally, reports of the CPB and the WRR are discussed.

Since five years the Gazette studies the economic functioning of the welfare state (also called Sozialstaat in German, and État providence in French). The present column is relevant, because until now the welfare state has been discussed merely indirectly. During the first years the focus was on the general economic models, and in the subsequent years the attention shifted to political economics. Only two years ago the welfare state obtained a prominent place, when several columns were dedicated to the radical centre. Here it became clear, that this political current can only be judged, when one disposes of some insight in the functioning of the welfare state itself.

The present column once more summarizes the already presented insights, and adds new ones. On the one hand, the tasks of the welfare state will be studied. On the other hand, the structures of the organization will be studied, which allow to execute these tasks well. It is already now remarked, that the welfare state must at least realize the social security and the redistribution of incomes. This fills the needs of the people, who by bad luck can insufficiently pay the expenses of living. The redistribution and the supply of benefits and support also guarantee, that the society functions well, that is to say, remains stable. It contributes to the legitimacy of the administration1.

The welfare state is constructed as a coherent set of institutions. Here institutions are interpreted as informal and formal rules of behaviour, which are prevalent in certain groups. The state is the group, which includes all others. Within the new institutional economics (in short NIE) the idea is propagated, that the social institutions develop in an evolutionary process. Only the most efficient institutions persevere, and therefore push out the unsound institutions. In this manner the NIE tries to explain the development of the economic system.

Institutions are always connected to the morals of the concerned group. Therefore institutionalism is based on the knowledge about group formation. The Gazette has studied group theory in two columns. It originates mainly from the social psychology. In economics the Dutchman P. Frijters has proposed the following interesting taxonomy of groups2. The origin of all groups is the network, which consists of a set of loose contacts between individuals and groups. Since Frijters mainly studies the economic system, he limits his analysis to networks within economic markets. Although the competition on the market often stimulates the efficiency, yet sometimes the (transaction-)costs can be reduced by cooperating in groups. The group has the advantage, that her institutions make the behaviour predictable, which stimulates investments.

The taxonomy of Frijters separates the groups according to their size and reciprocity. In a small group the institutions are protected by informal social control. But in the large group there is anonimity, so that opportunistic behaviour can pay, and a formal maintenance becomes necessary. In the reciprocal group all members are equal, so that she is (more or less) democratic. The hierarchical group has a leader at the top, who has sufficient authority to make all decisions by himself. Thus there are 2x2=4 archetypes of groups, each with her own institutions. The circumstances determine, which archetype is most effective. Although institutions are rather durable, they adapt to the dynamics of the environment. For instance, in the end the absolutist state changed into a democratic state.

The theory of networks and groups is supported widely by sociologists. Typical is the view of the Dutch sociologist A.C Zijderveld3. Zijderveld distinguishes the groups according to the degree of bonding (cohesion). The hallmark of a thin network is the loose contacts, like those on the market. The personal interest is leading, and the relations are volatile. A thick network has some durability and cohesion, which is accompanied by common morals. There are also thin and thick institutions. The thick network actually disposes of thin institutions. Here the idea of Frijters emerges, that groups are born in the network4. Thick institutions can be found in the traditional group, and then they are rather coercive. In this situation the individual freedom is restricted to such an extent, that the group resembles a hierarchical structure. Consider again the absolutist state.

Zijderveld clashes with Frijters in his taxonomy, and your columnist believes that the categories of Zijderveld are slightly less fruitful. Zijderveld mainly wants to defend modernism against post-modernism5. Thick institutions create alienation in the individual, a term which was made popular by Marx. Moreover, they exclude outsiders. But without institutions people become morally adrift, which the sociologist Durkheim calls anomy. The reference-points disappear. The evident advantage of thin institutions is, that they give room to diversity. This makes possible a personal interpretation, so that the institution can be internalized better. With the rise of individualism the call for personal autonomy increases. One must again and again find the right mix of the market, state, and civil society. The welfare state itself is thin, because the bureaucracy values efficiency (organic solidarity).

Immediately after the Second Worldwar some believed, that the welfare state is the rational consequence of industrialization. It would be a necessary instrument for making industrialization possible. But this idea is too simple. Since institutions are related to morals, they introduce value rationality in human actions. That is to say, the goal does not always justify the means. This plays down the importance of instrumental rationality (consequentialism, functionalism). Thanks to the shared morals there is a rudimentary will of the people. so that the state and its politics can define the general interest. The structure of the state is determined completely by the regional culture and morals. Precisely this fact is at the origin of the theme of the present column! The state legitimizes its existence by propagating and furthering the general interest6. Man can be only truly free by means of laws, first of all the Constitution.

The interest is a subjective utility, and can be related to morals. Therefore the elaboration of the general interest is always controversial. The same even holds for the so-called natural rights, such as the protection against violence. But the individual freedom of the market alone does not guarantee a distributing justice. Almost all people also include the social justice in the general interest. That is to say, it satisfies a need, and furthers the social cohesion. Thus the social rights can be defined. Interests can be translated into institutions, such as public goods. In the modern state the institutions must remain thin, fairly neutral, so that the unavoidable morals do not become unbearable. Yet the regional morals lead to specific institutions, so that the various states are globally quite different.

Thus a mixed economy is formed. The state reconciles the freedom of the market and the morals of the civil society. This idea has been propagated mainly by the sociologist K. Polanyi, who identifies the political system by the central redistribution, the economic market, and the social reciprocity7. Loyal readers of the Gazette are familiar with the theory of Polanyi as a consequence of the triangle-scheme of the German sociologist H. Ganßmann, which has become a frequent point of reference during the past five years8. Ganßmann believes, that the welfare state must mainly insure its citizens against risks. Risks can also be reduced by means of prevention and care. In his eyes the security is realized in the so-called K-game, the conflict of interests between labour and capital. However, this traditional conflict theory of the social-democracy does not do justice to the enormous diversity of national institutions.

Modern science more or less takes into account the national morals by distinguishing various categories of institutional systems in policy analysis. So an attempt is made to categorize the states in clusters, which each roughly belongs to a single category. Next for each category the performances of the states in the concerned cluster are analyzed, for instance with regard to economic growth. In this way it can be shown, that some systems of institutions indeed have an evolutionary lead over others. The better systems have a competitive advantage. Incidentally, the expectations of this scientific method must not be too high. It is already quite something, when it reveals some rough contours in the general chaos of the existing social activities.

An interesting model has been proposed by the economists D. Acemoglu and J. Robinson, in their famous book Why nations fail9. It has already been mentioned many times in the Gazette. The authors mainly test their model with the huge political differences between North- and South-America. Of old the institutions in North-America are superior. Another example, somewhat less dramatic, is the difference between West- and East-Europe. Historically, Russia and the Habsburg Empire were ruled by absolutism until the nineteenth century. This is especially noticeable at the start of the industrialization. Only after 1990 the democracies in South-America are formed. Africa is also a continent with miserable institions. Worst is of course the situation, where a state hardly has any institutions (for instance at the moment Somalia or Libya). Then it is actually failed, because there is no centralization.

Partly due to the interaction between politics and the economy, small differences between states can lead to totally different paths of development. Therefore the future of states is often determined by random incidents, which make an institutional revolution possible. The paths of development are called institutional drift, because the evolution occurs by means of vicious circles and upward spirals. Then the quality of the original institutions is very important10. The nasty implication is, that societies of weak states will increasingly lag behind in comparison with the modern states.

The hallmark of sound institutions is inclusion, both economically and politically. It protects the freedom rights. The legal system is neutral, so that the property rights are guaranteed. Such a system gives positive incentives. In inclusive institutions the entrepreneurs can gain by means of investments and innovations. Innovations are important for the social evolution, also in political respect. The people must be able to replace a failing regime by a better one. This explains why especially entrepreneurs benefit from the establishment of inclusive political institutions. When desired, they form coalitions with other interest groups (pluralism). The civil society establishes schools and independent news media. It is again stressed, that the political and economic freedoms are interwoven. For instance, a democracy, which prefers central planning, is no longer optimally inclusive! The economic incentives weaken11.

On the other hand, in South-America and Africa the extractive institutions dominate. That is to say, a small elite has all power, so that they can levy high taxes and appropriate the monopoly of profitable activities. The room for innovations is small, because these often harm the interests of the established elite. The elite promotes more her own interests than the general interest. The increasing wealth of the elite can be accompanied by increasing poverty of the population. Then the political change occurs by means of coup d'états, because only in this manner the competing elites get access to wealth. Therefore the social stability is less than in inclusive states12. The table 1 summarizes the categories of Acemogu and Robinson. In addition, several typical states are mentioned. The column with population numbers is a very rough estimate of the global presence per category.

| source | category | example | total population (order of magnitude) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acemoglu and Robinson | inclusive institutions | Great Britain, United States of America | 1 billion |

| extractive institutions | Congo, Guatemala, North-Corea | 1 billion | |

| hardly any central authority | Somalia, Sierra Leone, Libya | 100 million | |

| Giddens | conservative liberalism | Reagan, Thatcher | |

| social liberalism | Clinton, Blair, Schröder | ||

| Fukuyama | trust in society | Japan, Germany | 1 billion |

| trust in family | China, central Italy; | 1 billion | |

| hardly any trust | South Italy | 100 million | |

| Esping-Andersen | Scandinavian regime | Sweden | 10 million |

| continental regime | Germany, France | 100 million | |

| Anglosaxon regime | Great Britain, United States of America | 1 billion | |

| mediterranean regime | Italy, Spain | 100 million | miljard

Of course lots of African state provide the best illustration of the disadvantage of extractive institutions. But also the Leninist (socialist) regimes are extractive. At first sight this is surprising, because they do realize a kind of welfare state. However, the survival of the Leninist party and its elite have the highest priority. The party combats pluralism, and stifles the natural human rights13. This discourages personal efforts, and stifles innovation. Here loyal readers recognize comparable conclusions in the Gazette. Although some welfare is realized, these do not automatically lead to inclusive institutions. This observation makes Acemoglu and Robinson pessimistic about the future of China, which actually also has a Leninist regime. This enormous state will remain economically dependent on innovations, which the free (inclusive, pluralistic) world has realized14.

The classification in categories according to Acemoglu and Robinson gives little information about the origins of the welfare state. For, states with extractive institutions or even without central authority are rarely a welfare state. Only the states in the category with inclusive institutions dispose of the means, which are needed for the maintenance of the welfare state. Conversely, the social security is only really required, when the state must legitimize itself democratically. The model is mainly instructive, because it stresses, that precisely the Anglosaxon states succeeded in the continuation of the upward spiral towards inclusive institutions15. During the same period for instance France and Germany are still stuck in absolutism. Apparently liberalism is needed in order to realize the welfare state. This is also the message of the radical centre, which has been mentioned in the introduction of the column.

Although this political current is diverse, yet Anthony Giddens can be called its most prominent ideologist16. Giddens is not interested in extractive regimes. He uses roughly two categories, namely conservative liberalism and social liberalism. Conservative liberalism is generally called neo-liberalism. Giddens connects this with the then policies of Reagan and Thatcher. They preferred free economic markets, combined with a traditional (thick) society. Social liberalism is propagated by the current of the radical centre, which emerges from the social-democracy. It values free markets, and besides wants a liberal society. This implies, that the citizens can claim social rights. Thomas Meyer, a German congenial of Giddens, even places these rights at the centre of his arguments.

The paradigm of the radical centre is related to the inclusion model, but it is more radical in the promotion of inclusion. Contrary to the inclusion model, there are no states, which personify the radical centre. The two categories of Giddens intend to evaluate the current policies, and these are different for each government (see table 1). For instance, in Great-Britain the liberal policy under Thatcher was conservative, whereas under Blair it was social. The same change is observed in the United States of America, with on the one hand Reagan and G.W. Bush, and on the other hand B. Clinton. Dependent on the currently ruling government, the liberal welfare state develops in a conservative or liberal direction. So the paradigm of Giddens is dynamic. In each category the policy goals are independent of the evolutionary path, although the policy instruments do follow paths17.

The inclusion model and the paradigm of the radical centre make clear, that the actions of the political elite determine whether the welfare state will emerge. Besides it has been explained, that the value-rationality of the ruling elite affects the formulation of the general interest. She defines the social rights, including the social security. Therefore the sociologist F. Fukuyama has studied the cultural differences between states. The present paragraph consults his book Trust (in short Tr)18. Fukuyama indeed believes, that a national culture of mutual trust among the people has a positive influence on the economy. Just liberalism is not yet a guarantee for a high economic growth19. Trust is a part of the social capital (Cs, with s of social), because it stimulates the mutual cooperation. This reduces the transaction-costs.

However, Fukuyama analyzes a different part of Cs, namely the cultural skill to form groups. He calls this type of capital the spontaneous sociability (in short Co)20. In fact Co also measures the degree of inclusion. The national inclination to be spontaneously social Co partly determines the socio-economic structure of the state. For, group formation is indispensable for establishing the institutions of the welfare state. When the citizens themselves realize the social security, by means of the civil society or the market, then costly state coercion is avoided. Groups with a very low Co are rare. Fukuyama mentions as an example South-Italy, and the black ghetto's in American towns (chapters 10 and 25, and p.337 in Tr; see the table 1). They are the breeding ground for criminality. The state itself must maintain order. Even family life is poorly developed.

The family as an institution has a smaller size than for instance the church or the state. In almost all cultures Co in the family is naturally large. The family is essential. Enterprises commonly begin their existence as a family activity. Then the family itself can take care of social security and redistribution. However, in modernism the social security becomes an affair of very large collectives (organic solidarity). In many cultures a high Co also exists beyond the family, so that large private organizations can be established for regulating the social security. These organizations are a part of the civil society. Fukuyama praises the advantages of such cultures. He mentions as the classic example of this type of state Germany and Japan (see the table 1). In cultures where the private initiative fails, the state itself must organize the social security. Here France and Taiwan (or China) are examples21.

Incidentally, Fukuyama is primarily interested in the economic structure, and not in the social security. But these two are naturally intimately intertwined. He limits his analysis to democracies, so to inclusive systems. Leninist systems, such as in China, are extractive: they stifle the civil society, and thus destroy Co (p.54). He states, that democratic systems with a tradition of central absolutism, such as Taiwan, France and South-Italy, also have difficulty in increasing Co. However, it is indispensable, when one wants to engage in reciprocal obligations for the long term. Therefore Fukuyama pays much (positive) attention to the Japanese culture. The high Japanese Co creates an atmosphere, where the family enterprise can be transformed in shareholder companies. There is sufficient willingness to appoint skilled workers from beyond the family in leading positions (inclusion). This furthers the continuity of the enterprise.

The high Japanese Co is also very beneficial for forming hybrid economic organizations, which are neither a market, nor an enterprise. These are thick networks, which are called keiretsu (p.162, chapter 17 in Tr). The enterprises in the network mutually engage in durable relations. For instance, the Sumimoto and Mitsubishi have such a structure. The participants in the group benefit from the advantages of scale in the production, and reduce their own entrepreneurial risk. The workers also benefit from the reciprocal solidarity. Thus the social security is to a significant degree realized within the group of enterprises (p.218). Notably the larger enterprises are prepared to invest in their workers22. Thus the public sector can remain small! Fukuyama believes, that the German corporatism is based on the same principles as the keiretsu, although it is more formal and therefore less flexible.

Apparently the welfare state can be quite diverse. A part of the security and facilities can be supplied in an informal manner, within the private market. Furthermore, Fukuyama believes, that a high Co is essential for establishing big industries. In states such as France an Taiwan merely the shopkeepers and small entrepreneurs emerge spontaneoulsy. The absence of big industries makes the economy one-sided, and therefore vulnerable to global developments. The state can try to energetically stimulate the big industries, such as in South-Corea. But then there is the danger of a lack of efficiency and sometimes of corruption. Fukuyama believes, that traditionally also the United States of America dispose of much Co23. However, it has been negatively affected since the sixties of the last century, also as a result of the counter culture movement. The individual obligations and rights become unbalanced (p.314). See also the analyses of the sociologist Putnam.

All in all, Fukuyama rightly points to the advantages of self-organization, such as security and efficiency. Moreover, then the solidarity is truly personal. Japanese ideas, such as lean production, quality circles, and self-managing teams have now been diffused all over the world. Incidentally, Co can not be organized rationally. For, it is transferred by means of culture. But Fukuyama also warns against the harmful side-effects of a high Co, such as the isolation of outsiders (p.252). This slows down innovation. Therefore critics sometimes condescendingly talk about nepotism (with respect to close families) or about crony capitalism (with respect to nationalistic states, or close circles of enterprises). In such situations the thick institutions are naturally dominant.

The inclusion model and the trust model analyze the culture and the politics of the welfare state. However, the Swedish economist G. Esping-Andersen studies the instruments of the welfare state. For, he argues, that these instruments emerge logically from the path of political development of the concerned state. The present paragraph consults his book The three worlds of welfare capitalism (in short Twc)24. The book dates from over a quarter of a century ago, and therefore its contents is outdated, because since then the welfare state has evidently changed significantly. However, Esping-Andersen has proposed a classification in three categories, which nowadays are still popular. He distinguishes between the Scandinavian, continental and Anglosaxon regime of the welfare state. Others have added the mediterranean regime, in order to include and model in this scheme also South-Europe. See the table 1.

The table 1 illustrates, that the classification is peculiar. For, the Scandinavian states are insignificant on a global scale. But just like Fukuyama is fascinated by the Japanese state, so Esping-Andersen adores the Swedish state25. In reality Twc is mainly a comparative study of Sweden, West-Germany and the United States of America (in short USA). Central in Twc is the change, which the welfare state undergoes during the period 1960-1985. Then the industrial state enters its post-Fordistic phase. The relative share of the industries in the economy declines to the benefit of the expanding sector of services. According to Twc the path of this transformation depends on the social institutions, which are again the result of the structural distribution of political power. In Sweden the social-democracy dominates, in Germany the christian-democracy, and in the USA the liberalism26.

Therefore these three states prefer a different policy mix. In Sweden the state determines the policies. Germany prefers (neo-)corporatism. And the policies of the USA are market-oriented. The path of the welfare state is notably determined by the arrangement of the labour market (p.221 in Twc). For, during the transition to the post-Fordism a policy intervention is needed with regard to the declining employment in the industries. In Sweden the public services are rigorously expanded, such as welfare activities, health care and education27. They are universal. This is paid by means of taxes, so that actually an artificial demand is created. In Germany the supply on the labour market has been reduced, by discouraging the participation of women and older workers. Therefore the society is split in insiders and outsiders. The outsiders are a financial burden. There is a class society (p.60).

The USA introduce free markets in the employment exchange. This indeed reduces the unemployment, but also leads to the establishment of a low-wage sector. Moreover, the supply of social services is partly private, so that their use by the lowest incomes is limited (as a result of free choice or not). The enterprises themselves create some social security, just like in Japan (p.203 and 225). Thus the three paths lead to three different regimes. This is not a new discovery. The merit of Esping-Andersen is, that he has developed a composite index of national peculiarities, which has clearly different values for the three regimes (p.54 in Twc). The index value is 39.1 for Sweden, 27.7 for Germany, and 13.8 for the USA (p.52). In Twc the index has been calculated for 18 western industrial states, for the year 1980. According to Esping-Andersen these states form clusters around index-values of roughly 18, 27 and 35.

According to Twc this means, that the diversity of welfare states can be reduced to the Scandinavian, continental and Anglosaxon regime. The clustering is even more apparent, when the states are ordered by means of seven political indices for the typical social-democratic, conservative and liberal hallmarks (p.74). This looks like a sound approach. However, here the problem is, that al these indices have been defined in a rather peculiar manner. Moreover, the results are sometimes strange. For instance, Japan has almost the same composite index as France (respectively 27.1 and 27.5). Then when the political indices are dissected it turns out that Japan is more liberal, whereas France is more conservative. Apparently most regimes are yet a mix of the three categories. Therefore your columnist is not very impressed by the findings of Esping-Andersen28.

The column ends with a reference to two reports of Dutch institutes for policy analysis, namely the Centraal Planbureau (CPB) and the Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid (WRR, scientific council). The reports both use the three-worlds model, although they each have their own interpretation. It is instructive to see how such a model is applied in practice. Besides, their arguments can be compared with the insights of the present column.

In 2016 the CPB published the report Uitdagingen en beleidsrichtingen voor de Nederlandse welvaartsstaat (Challenges and policy directions ...). The report states that the categories in the three-worlds model are merely ideal types. Therefore it is mainly applied to the policy instruments, which can be corporative, means-tested or universal. The report merely wants to transfer knowledge, and therefore does not express a preference for a certain category. The welfare state has three tasks, namely insurance, redistribution and protection. So the report emphasizes the economic function of the welfare state. Here the protection is mainly studied for the labour market, where in general the factor capital is more powerful than the workers.

The report states, that the power is unevenly distributed among the workers, which makes the Dutch labour market dual. The position of workers with little education is so weak, that they get less social rights than the others. This is incompatible with the principle of justice of the welfare state. The inequality of the rights can be reduced by means of a corporative, means-tested or univeral policy. In corporatism a strong regulation is preferred. However, it wants to realize policies made to measure in each sector, and therefore accepts some inequality among the workers. The regulation is partly executed by the associations of enterprises and workers, so that the state intervention is limited29.

In the means-tested policy the rights of the more powerful workers are reduced. For, they can meet their own needs by means of private arrangements. This remedies the injustice. The austerity of the arrangements incites the workers to perform better. It is obvious that not everybody can cope with this pressure. But the security of the poorest is guaranteed by means-tested instruments. In the universal policy everybody also has the same rights, but now at a higher level. Therefore such a system requires centralism. The payment of the costs leads to a high burden on labour, which affects the employment. Also the individual freedom to consume is curtailed. Besides, generous rights invite to engage in free riding and moral hazards. The supervision on the use increases the costs of execution30.

Politics must make a choice from the policy alternatives. Your columnist concludes, that the means-tested policy is attractive. However, there are limits on the human capacity to bear insecurity and personal responsibility. Therefore, in practice a policy mix is needed. According to the report the Dutch regime is at present still characterized by a mix of corporative and universal instruments.

In 2006 the WRR published the report De verzorgingsstaat herwogen (Regauging the welfare state). In this report the three-worlds model is used for a comparison of the European welfare states. Moreover, this model is extended with the mediterranean category, which is found in South-Europe. This category resembles the continental regime, but the benefits are less generous. Therefore the family remains important as a source of support. See the table 1. But all in all the report rejects the analysis in terms of pure regimes (see p.75, 92 and 262). Each state has its own evolutionary path, and a successful policy can not be transfered from one state to another without problems. Besides, the report concludes, that partly due to the European Union the various regimes converge to a single standard.

The report defines the welfare state in an original and therefore deviating manner. It identifies as tasks the insurance, caring, bonding and emancipation. So here it prefers a broad definition of the welfare state. The bonding must create a social cohesion. Since the bonding must also occur in material affairs (see p.37 amd 50), this concept includes the task of redistribution. Chapter 8 contains a plea to bond poor and rich, young and old, and natives and migrants. In each of these three cases work and income are essential31. The emancipation must take place in education and on the labour market (chapter 7). Thus the foundation is laid for a kind meritocracy (p.183)32. The report is fairly satisfied about the present insurance and caring. However, the policy of bonding and emancipation allows for much improvement (p.53)33.

According to the trust model the institutions of the welfare state depend on the national culture. The report takes as the starting point, that Dutchmen want to live in a kind meritocracy (p.183). They accept the human limitations (p.259). The aim is self-unfolding in the context of the community (p.73)34. Therefore the economic competition and the social justice must be reconciled. This is indeed possible, although it would be an exaggeration to call the social justice a production factor (p.90). For, it turns out that both the Scandinavian ("socialist") and the Anglosaxon ("liberal") welfare state are durable (p.91)35.

The report is extensive and makes many proposals for more effective policies. The reader is encouraged to form his own opinion. As an illustration, your columnist makes some comments about the fascinating part, where an increase of the expenditures on education is advocated. It is desirable to have pre-school day nursery, combined with education, where the expensive Scandinavian regime of a universal supply is preferred (p.175 and 211). The formation of new generations is (partly) a public responsibility (p.212). Children must get an offer of a wide pallet of social, cultural, sport- and cognivite opportunities (p.254). Besides, there is a plea for higher expenditures also elsewhere in education. On p.196 it is stated, that more education is better than less. This all fits well with a welfare state, which invests in human capital (p.259).

It would be great, when indeed the social problems could be solved so easily. The expertise of the report is naturally beyond doubt. Yet your columnist has the impression, that this argument is very doctrinal. Gigantic policy programs and radical reforms rarely solve the practical problems36. The universal regime in Sweden is not really an ideal state, with its large public sector and high taxes. Neither could the extensive educational system in the former Leninist states solve the social misery. It is wrong to expect from the state, that it can form its citizens at will. Self-organization is principally preferable, because it reinforces the autonomy. Your columnist hopes to further elaborate on these problems in future contributions!37.