Figure 1: caricature Abraham Kuyper

as a shadow above the Heemskerk

administation (Albert Hahn, 1908)

The Gazette studies since at least four years the importance of national institutions. The individual and social advantages of institutions can be illustrated with rational arguments. However, the human psyche imposes clear limits on rationality. Institutions are quite rigid. They exhibit a variety, which is determined by culture. And they are obviously a source of power. Theoreticians want to establish categories of national regimes, but this is quite difficult. For, institutions partly emerge due to spontaneous diffusion. Finally, the ideas of the economist Liefmann are studied.

Since its establishment the Gazette studies social actions, just like in the past its namegiver Sam de Wolff did. De Wolff still had to use class theory as his starting point. Since then the insight in collective action has increased significantly. Collective action interacts with the social institutions. The action forms these institutions, and is also restricted by them. The institutions are indispensable for maintaining the stability of society1. In other words, the system of institutions allows to manage society. Many equilibriums with corresponding institutions are conceivable. In the ideal case an optimal equilibrium is realized, where the social welfare function has its maximal value. It is scientifically controversial whether this can generally be achieved2.

The present blog describes a number of modern and dominating theories, and also consults the blogs from previous years. A lot of attention is paid to the economic system, because economic growth is indispensable for the unfolding of individual persons. The argument tries to adhere to methodological individualism, whenever possible. The argument is divided in three phases. In each phase the actor model is modified somewhat, corresponding to the nature of the studied process. First the emergence of institutions, including the state, is explained as a process of rational choice3. Next the social psychology is used in order to describe the dynamic change of institutions. Finally the theory of public administration is used in order to explain the development of the administrative regime.

When reference is made to the social administration, then at the moment this is still primarily the national state. In abstract terms, the state must supply public facilities, because these can not be supplied by the private markets4. The most important provision is the legal system. The national law consists of a set of formal institutions. They have usually emerged from the informal institutions, this is to say, from the traditional habits and convictions. For, therefore they already have some support after their formal introduction. This is called rule harmony5.

At the top of the legal order is the constitution6. It can be interpreted as a social contract, which is concluded by the citizens in consensus, in order to regulate their mutual interactions7. The constitution imposes the general and binding framework for detailed legislation. The introduction of property rights is very important for the functioning of the social system8.

It has just been stated, that the administration and its institutions protect the social stability. They solve a number of social problems. First, the administration guarantees, that the safety of each individual actor is maintained. It remains uncertain, what the natural form of human existence is (without administation). According to the philosopher Hobbes a war of all against all will develop. Your blogger believes, that this may well be true, but anarchists have a different view. The property rights eliminate a lot of sources of conflict. But even when the natural state would be peaceful, then the administration is still needed in order to correct the so-called external effects. For, individual actions often lead to consequences for other actors. This holds in particular for the public services, which improve the general wellbeing9.

Finally the administration can aim to reduce the transaction costs of the citizens10. The interactions between actors can only unfold in a satisfactory manner, when sufficient information is available, binding agreements are possible, and the fulfilment of contracts is enforced. The government can take care in an effective and efficient manner, that such conditions are satisfied11. In this way the administration eases the burden of the citizens, this is to say, it reduces the costs of social transactions.

The total of formal and informal institutions determines the manners in society. They are called a collective or shared mental model12. This already suggests, that the institutions are a psychic phenomenon. Institutions do not form in a purely rational way, guided by calculations of the social interests. Although their aim is to minimize the transaction costs, their formation is the result of a power-struggle between groups13. Often this ends in a compromise between the groups. But when a certain group is very powerful, and unilaterally imposes its will, then it is even conceivable, that the total of all transaction costs will rise. There is exclusion. Then the powerful group spreads its own institutions across the whole society14. So it is desirable to study the spreading of institutions.

Institutions can be realized in three ways. Society can be forced to accept them, by means of supervision and enforcement. This is an expensive solution. The society can also exert a collective pressure to accept the institutions. This is the most usual way. Then the institutions must naturally already have some support at the start. And finally society can make propaganda to internalize the institutions. The institutions become a part of the personal identity. This situation would be ideal15. However, this is difficult to realize in a pluralistic society16. In reality all three ways will contribute somewhat to the support for the institution. This is described well in Sozialpsychologie (in short SP)17.

An actor has an interest to belong to groups18. Furthermore, groups gain in external strength, according as the internal cohesion increases. Therefore the members of a group have a natural inclination to comply with the rest. In addition they can be convinced by the information of the group (p.285, 372 in SP). Members do not want to give offense, because this weakens their personal position within the group (p.289). Thus group norms (institutions) are formed. Respect for the institutions is an obligation (p.302, 318). Reciprocity is valued, and dissonance is avoided (p.303, 318). The approval of the group is more important than the personal opinion (p.290)19. An actor only sticks to his opinion, when his personal interest is large (p.294). Sometimes within the group a minority forms, with a different view (diverging ideas) (p.296). It hurts the cohesion, but stimulates innovation20.

Psychology also argues, that institutions such as group norms make interactions more predictable within the group (p.341). This is the positive side of coherence (p.347). Certainly for large groups the institutions are important, because the personal ties are less strong. The famous economist M. Olson has argued, that a large interest group is really a public good. Then it is attractive for individual actors to engage in free riding on the group effort21. Sometimes symbols are used for bonding, such as wearing uniforms, which impose a role (p.341). Roles couple norms to a function, and create expectations about behaviour (p.343). A role can even lead to deindividuation (p.344)22. Bonding and status are not institutions themselves, but they do help in maintaining institutions (p.349). The goals and means both are a part of the structure of the group (p.347).

The state tries to bind its citizens by means of an ideology, and by means of national symbols and culture. Nevertheless, the state is not a group in the psychological meaning of the word. There are various social groups active, which compete mutually. The citizens experience this more as a conflict and struggle between subgroups than as the influence of a loyal minority. Thus within the state there are prejudices between groups, which even can result in discrimination (chapter 10 in SP)23. Prejudices are heuristics. The cognition classifies the actors as stereotypes (p.379)24. But next the stereotype gets an affective (emotional) charge (p.379). Therefore the struggle between groups is no longer purely rational. Apparently also psychology concludes, that institutions are partly determined by the relations of power. Usually reason will yet get the upper hand. But in case of excesses the state can even fail25.

Furthermore, not all actors will be equally inclined to join a group or organization. The consequence is, that the interests of some citizens are better served than those of others. According to Olson especially the interests, which are widely spread in society (for instance those of all tax payers) will lose in the power struggle between groups. Large groups are relatively powerless25.

The preceding argument confirms the hypothesis in a previous blog, that in many situations the actor model is rather complex. The personal interest is important, but sometimes yet the rational ideas fail. The heuristics can unintentionally have disastrous consequences. The spreading of institutions implies, that the actors continuously adapt their views. So it is not true, that the preferences of actors are constant, like the neoclassical paradigm assumes27. Nonetheless, the individual preferences naturally change quite slowly, and sometimes not at all. Often the social change is brought about by the decease of a generation. On the one hand, each actor has much freedom. On the other hand, the environment imposes severe restrictions28.

Apparently it takes an effort to build new institutions. This is an investment, which leads to costs. Therefore people want to maintain their existing institutions as much as possible29. Moreover the institutions form a coherent whole. It is difficult to renew a single institution, and yet maintain the coherence within the system. Changes, which undermine the consistency of the system, are not acceptable. Moreover a change often implies, that some groups are hurt. They will resist30. Furthermore the outcome of any change is uncertain. The uncertainty affects the utility of the change, because people are risk averse. All these factors imply, that there is a limit to the possible interventions in the system of institutions. It is said, that the development of the system is path dependent31. This is to say, institutions are rigid.

Nonetheless change is sometimes desirable. Routines create their own problems32. According to the systems theory the feedback of the obtained results leads to incentives for learning. Usually institutions are changed incrementally. A development in small staps weakens the mentioned inhibiting factors. This insight is included in among others the punctuated equilibrium theory (PET), and in the theory of Hayek33. Legislation often builds on jurisprudence. This is called common law34. However, when a radical reform offers really large advantages, which are obvious to everybody, then it wil yet be executed. This is called constitutional law35. When all states realize similar radical changes, then such systems will converge. The convergence has been predicted by, among others, Tinbergen and Wilensky36.

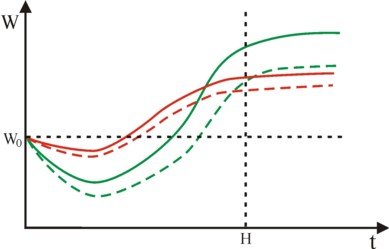

The figure 2 illustrates the described considerations of the citizens. At the time t=0 the wellbeing is W0. Suppose that the citizen has a time horizon t=H, and that his discount factor equals δ (with 0<δ<1). This assumption implies, that beyond this horizon H one has δt = 0. The citizen is slightly myopic. An incremental policy begins with some costs, which temporarily reduce the wellbeing. However, soon the policy leads to an improvement W(t) > W0. This is the solid red curve. Unfortunately at the start the value of W(t) is still somewhat uncertain. The citizen is risk averse, and therefore devalues W(t) to W'(t). This is the dashed red curve. Now the citizen will agree with the incremental policy, when he expects a positive nett utility:

(1) U(incremental) = Σt=0H δt × (W'(t) − W0) > 0.

Exactly the same argument holds for a radical reform. According to the green curve here the costs and benefits of W(t) are relatively large. Since moreover W(t) is rather uncertain, W'(t) will be somewhat further below W(t) (dashed curve). The result U(radical) is calculated in the same way as U(incremental) in the formula 1. The citizen will prefer the radical reform above the incremental policy, when U(radical) > U(incremental) holds. Thus the preference for an incremental policy becomes clear. For, the radical reform (the dashed green curve) can be rejected in favour of the incremental policy (idem in red), even when in the end on t=H one has W(incremental) < W(radical). Then the citizen simply does not want to bear the high costs in the short term.

In this paragraph the system of the state is studied more in detail. This system determines how the policy formation develops. Unfortunately, at the moment a general theory of the administration of the state does not yet exist37. In this paragraph attention is paid to three aspects, namely the constitutional structure, the political system, and the role of interest groups. The idea of this approach is evidently to describe the institutions, and to analyze how they function. Thus it becomes clearer, which paths a society can follow38. The reader is requested to always remember the psychological motives, which are the basis of the described institutions.

The state has a formal hierarchy, just like any other organization. The hierarcy is dictated by the national constitution. The constitution is usually based on the trias politica, this is to say, the separation of powers in a legislative body (parliament), an executive body (government), and a judicial body (judges). The separation of powers makes the probability of an abuse of power smaller. Various variants of the trias political are conceivable39. For instance, parliament can consist of a single house, or of several houses (usually two). Sometimes the government is led by a president with his own democratic mandate. The electoral system can distribute the seats in parliament according to the majority (district system), or proportionally. In the first case there are often two large parties. The one who wins the election, can itself form the government.

Furthermore, the state can be central or decentral. In the decentral system the state is a federation, with member-states. The state shares the administrative tasks with its member states. The federal administration is layered, but due to this division of tasks there is no strict hierarchy. A member-state is not a lower administration, like a province. This is called poly-centrism. The competences of the federation and member-states are documented in the constitution. The advantage of a federation is, that the decentral actors have more autonomy. The disadvantage is, that actions are more cumbersome. There is insufficient coordination of policies, and impasses are frequent. Scharpf calls this the joint-decision trap40.

The spreading of power by a division of tasks implies, that the concerned actors need each other. They are mutually dependent. No single actor can unilaterally dictate the whole state policy. Each actor in the action arena has some veto-power. Thanks to the balance of powers the groups have less opportunities to exploit others.

The political parties usually recrute their candidate members of parliament and of the government from their rank-and-file. Political parties have two goals: they make propaganda for a certain ideology, and they want to acquire paid functions for their members. They can only reach their goals, when they succeed in binding sufficient voters41. In the west there are traditionally three political currents, namely conservatism (in the past: christian-democracy), liberalism, and the social-democracy (in the past: socialism). During the first half of the twentieth century perhaps the most important political theme was the struggle resulting from different interests between labour and capital. Nowadays this is no longer the case, at least in the west (say, the OECD states)42. The parties must obviously take into account the feelings, which live within the population.

Many attempts have been made to measure the ideology of parties. It turns out that this is quite difficult43. A problem is that each party must adapt to the national peculiarities. Again and again the context of the ideology also turns out to be important. This undermines the universality of the ideology. The context can also be international, for instance the economic globalization44.

Philosophers assume, that the citizens choose their own constitution, as well as their government. But practice reveals, that the turn-out on elections is never 100%. And percentages below 50% are not uncommon. It is indeed difficult to explain rationally, that citizens vote. For, this single vote is never decisive45. The citizens probably yet interpret voting as an obligation. His choice is partially determined by his environment. In modernism each citizen is a member of many groups, so that his dedication is divided46.

The previous considerations have made clear that actors benefit from joining interest groups. This can be a political party. But usually the group defends a specific interest, for instance of professional workers. This is called a distribution coalition47. Examples are the trade unions, or associations of entrepreneurs. They seek rent from the state. The influence of associations is measured in terms of the density, concentration, and centralization48. A high density and degree of centralization further their power. Well organized workers push up their own wages. When this is not moderated by institutions, then the power of the distribution coalitions affects the economic growth49.

The state can institutionalize the deliberations with certain interest groups. Then the associations also get political tasks. This is called neo-corporatism50. It requires that the interest groups unite in federations. An advantage of neo-corporatism is, that the concerned actors can internalize some external effects of their actions51. In this case the extra power due to centralization is used for constructive agreements. But nowadays the latitude is reduced due to liberalization and deregulation52. They enforce a supply side policy. All in all the benefits of neo-corporatism are controversial53.

Incidentally, enterprises can also as separate actors exert influence on the state. This is particularly true for transnational enterprises, which are relatively mobile in their activities54. Sometimes the enterprises are mutually strongly intertwined, like in the financial sector.

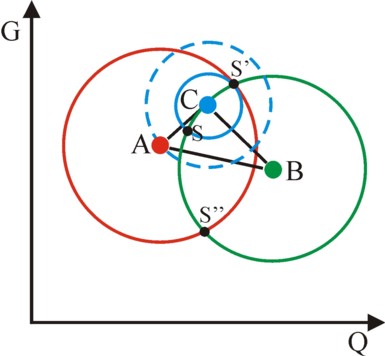

A recent blog has shown, that the control of the policy agenda gives a lot of power. This is an important subject in the theory of public administration. In certain circumstances the policy setter is even omni-potent. Your blogger copies the following argument from the famous textbook Public choice III55. See the figure 3. Suppose that there are three actors A, B and C, who must decide about a policy Q and a policy G. The present policy is represented by the point S. The preferences (optima) of A, B and C are the red, green and blue points. The actor A controls the agenda. For instance, A is the coalition of a minority government, and B and C are large parties outside of the coalition56. The figure 3 shows a spatial model, where the circles correspond to the indifference of the actors. They connect points with the same loss of utility with regard to the optimum.

A new policy will be accepted, when two of the three actors agree. In this situation it can be easily shown, that the actor A can stepwise realize his optimal policy (Q, G)! Namely, A first puts the new policy S' to the vote. This is a brilliant tactical move, because A himself will vote against it! For, according to A S' is less useful than S. But since B and C are indifferent with regard to S and S', yet S' will be accepted. In the second step A puts the new policy S'' to the vote. This is accepted with the support of A and B. In the final step A puts his own optimal policy to the vote. This is accepted with the support of A and C. Thus A has manipulated the agenda in such a manner, that in the end his optimal policy is supported. This is surprising, because the A-policy is less useful for B and C than the original S policy. The strategy of A works, because B and C are myopic. For, with some reflections they would be able to foresee the strategy of A57.

This model of the agenda setter has implications for institutions, because it shows that indeed the introduction of institutions partly depends on power, even in a democratic system. Furthermore it is a fascinating illustration of mathematical modelling in the theory of public administration.

The theory of path dependency has led to the theory of regime variety. The social development would correspond to a handful of regimes, which group themselves around the ideologies of conservatism, liberalism and socialism. This theory is described in a previous blog. In the version of Esping-Andersen there are fundamentally two regimes, one in the United States of America, and the other in Sweden. The remaining group was called the continental regime. This Three-Worlds model has a marxist basis58. More generally, nowadays a distinction is made between liberal and coordinating policies59. Evidently the liberal regime is also coordinated, but this is done preferably by means of free markets. Decisive is the intensity of interventions. Previously, this blog concluded, that the ideology and culture shape the regime60.

In practice the theory of regimes is unsatisfactory. Namely, the categories are merely ideal types. But the mixture of ideology and culture leads to a large diversity in regimes, which can not really be analyzed with just a few categories61. The citizens can get very attached to their own regime. But the OECD states are still similar to such an extent, that for instance their economic growth hardly differs. The growth rate is mainly determined by the welfare level, because poorer states benefit from a catch up effect62. Regimes become only hurtful, when they suffer from mismanagement, such as corruption, patronage, a rigid bureaucracy, or a weak constitutional state. This kind of regimes is especially found in the developing states63.

An alternative for the theory of regime varieties is presented by the theory of diffusion. It is more a description than an explanation. A local improvement can spread by means of learning, imitation or by means of an incentive for competition (best practice)64. Here it is assumed, that the process is unilateral, and therefore not collective65. In this sense diffusion differs from the already studied spread, where the group exerts pressure. Diffusion does require a connector between the concerned states66. The diffusion theory fits well with evolutionary models of development67. It assumes that truth exists, in the sense of best practices68. But diffusion does not guarantee, that the policy of states will per se converge69. Even block formation is possible, because diffusion works best between similar states70.

In this sense regime variety can be called morally good, because it allows for competition between regimes71. This is a search for the truth. New institutional economics (in short NIE) assumes, that knowledge spreads via diffusion also in free markets. Due to the incentive of competition this can lead to convergence on the market. But it is not certain, that an equilibrium is really established72. In this sense the theory of path dependency contradicts the equilibrium theory of the neoclassical paradigm. Another point of debate is the degree, in which markets are embedded within the society. The common view is still, that markets florish in the presence of a certain freedom73. Precisely for this reason the economy has been deregulated somewhat since the eighties.

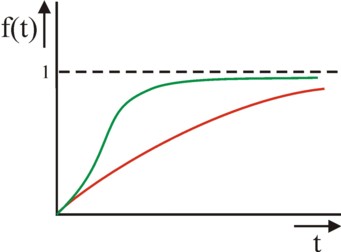

Diffusion can be described fairly accurately with the model of Bass74. In this model a new institution is realized by means of innovation or imitation. Innovation refers to a personal idea, for instance stimulated by competition. Suppose that at the time t=0 the fraction of states with a new institution equals f(0) = 0. At the time t the fraction (1 − f(t)) still uses the old institution. So innovation leads to a growth df/dt = α × (1 − f(t)) of the new institution, where α represents the capacity to innovate. Furthermore, imitation yields a growth β × f(t) × (1 − f(t)), where β is the capacity to imitate. Since imitation is an interaction, two fractions are present in the expression. Thus the growth equation of the new institution is:

(2) df/dt = (α + β×f) × (1 − f)

The figure 4 shows the development of f(t) for β=0 (no imitation) and β>0 75. It is clear, that the diffusion is accelerated thanks to the imitation. And since the growth due to imitation is proportional to f(t), imitation becomes more and more important for growth. The growth has an S shape. However, note that this diffusion model does not describe the learning process, which is the basis for the imitation. This would require the use of a learning theory76.

The blog started with the hypothesis, that institutions help to reduce the transaction costs, so that they make the society more effective and efficient. But next a psychological analysis of groups showed, that the decisions in groups have irrational aspects, or at least are not very transparent. Often institutions are an expression of group power, and this can lead to conflicts with the social interests. In pluralism especially the large groups are weak, because by their nature they have a poor cohesion. Also the theory of the administration attaches much value to the power struggle between groups. This suggests, that institutions originate only to a limited degree from sound reason. They make behaviour predictable, but not per se socially effective.

The social evolution does play a role in forming effective institutions. For, states mutually compete for means. States with poor institutions will finally be pushed aside by effective states. This is a stimulus for states to learn from each other, so that good institutions can spread, for instance by means of diffusion. But although the evolution punishes irrational behaviour, nonetheless the evolution of institutions can proceed irrationally. For instance, an aggressive state can subjugate and exploit the others. Therefore the evolution is not a reliable substitute for sound reason. A constructive evolution with ever better institutions requires, that the most powerful group itself applies sound reason, and uses an enlightened self-interest. It must take into account the interests of the others.

The economist Robert Liefmann (1874-1941) is mainly a philosopher77. He tries to describe the neoclassical paradigm in an era, when it was still in its infancy. This implies, that he wants to ignore social, moral and cultural phenomena in economics. Economics can not explain such phenomena, but must see them as an external fact. Therefore Liefmann opposes the Historical School. But the challenges for Liefmann are gigantic. In 1919 the general Walrasian theory of equilibrium is not yet common. Until now the Gazette has not yet explained this theory78. In short, the theory couples all present and future markets by means of product prices. Everything is mutually connected. Actors have complete knowledge about all markets, and therefore can determine an optimal strategy for themselves. Thus they maximize their own utility.

Liefmann still lives in an era, when the nett utility u (called Ertrag) is interpreted as the difference of benefits b and costs c. This has been described previously in a blog about the economist Wagner. Liefmann defines on p.273 in volume 1 of his book Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (2 volumes; in short GV) the economic principle as realizing the largest possible result (target, output, benefits b) with the smallest expenditure of means (input, costs c)79. Similar to Wagner he states that the benefits must be maximized, and the costs must be minimized. Here the benefits and costs are purely psychic. For instance the productive actor must bear the displeasure due to labour, and the loss of the means of production. Liefmann is aware of the enormous complexity of this optimization problem, albeit only vaguely. For, the actor has an almost unlimited freedom of choice.

Even his initial situation is undetermined, because his means are variable. He can vary his effort of labour at will. There is no border for the set of production possibilities80. So Liefmann denies, that the actor is subjected to a limited budget. In this respect his view differs from the modern neoclassical paradigm. The actor stops working, as soon as his nett utility threatens to become negative81. Liefmann also dislikes the theory of the partial equilibrium, which keeps prices or quantities constant, like in the Edgeworth box. Furthermore he clearly sees, that the actor must take into account the benefits in the distant future. The optimization has an inter-temporal character. The actor can decide to invest a part of his means. Here Liefmann interprets the benefits in a broad sense, and he also wants to include the social, moral and cultural preferences of the actor. Suppose that the actor can imagine K goals, then his total utility is82

(3) U = Σk=1K (bk − ck) = Σk=1K uk

Suppose that uk only depends on the variable qk, for instance the quantity of the good k 83. Then the actor must choose this qk in such a manner, that U is maximal for all k. This is expressed by the formula

(4) Σk=1K (∂uk/∂qk) × dqk = 0

The actor can increase his qk by working harder. In such a situation the dqk are all positive. Therefore the formula 4 leads to the requirement ∂uk/∂qk = 0. But Liefmann assumes, that the products are discrete. Consider the products k=1 en 2, with dq1 = -dq2 = 1, and keep the rest constant (dqk = 0). The exchange of products 1 and 2 implies that one has ∂u1/∂q1 = ∂u2/∂q2. In other words, in the optimum the marginal utilities (Grenzerträge) are identical (p.413 in GV1). This is the fundamental rule of Liefmann. The marginal utilities are not necessarily zero in the optimum, because qk can only vary in a discrete manner84.

Perhaps the reader notices, that product prices are absent in the argument of Liefmann. Apparently he does not like the second law of Gossen. Benefits and costs are purely psychical. Yet they can be expressed in money, namely by transforming them with the help of the utility of money bg. The utility of money is different for each actor, depending on his wealth y and other properties. The marginal utility of money is ∂bg/∂y. This illustrates again the complexity of human evaluations. When an actor receives a sum of money, then he must calculate how much nett utility this sum of money represents in his present situation.

Liefmann was ahead of his time in his search for a theory of the general equilibrium85. But he does not dispose of the mathematical techniques, which could present his ideas in a clear manner. He even dislikes mathematics (p.415, 445 in GV1)86. Therefore he has hardly contributed to the development of the modern neoclassical paradigm. Yet his ideas are present in modern concepts. For instance, the consumption outcome uk = bk − ck is clearly related to the compensated demand curve qk(p, b) for the product k. For, the marginal evaluation pk (willingness to pay, with k=1, ..., K) expresses the costs for the actor. The outcome uk can be calculated from the benefits and tne costs, with the help of the utility of money.