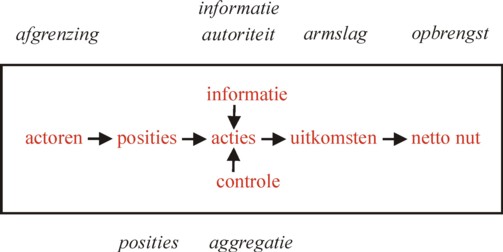

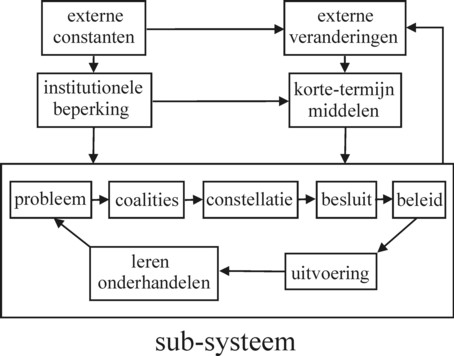

Figure 1: Scheme of institutional analysis:

variables and (outside of the arena) rules

For the sake of the inter-disciplinary approach a bridge is needed between the actor-institution analysis and the differentiation theory of sociology. The institutional analysis of Ostrom is described again. It is shown, that in many situations the homo economicus is willing to cooperate. Three system-theories are presented, namely of Parsons, Luhmann and Sabatier. Their advantages and drawbacks are summarized, as well as their implications for planning. The Leninist application of system theory is described.

Actor-centred institutionalism and the institutional analysis and development pay relatively much attention to the influence of strategic choices on problem situations. Sociology is not very interested in strategic behaviour. Those who appreciate an inter-disciplinary application of actor-institution paradigms, must bridge the gap with the sociological perspective. Reversely, it is important that analysts with a deductive orientation become aware of the sociological concepts, which underly the actor theories.

In several previous columns the institutional analysis and development (in short IAD) has been described as a variant of actor-centred institutionalism (ACI). This ignores the qualities of IAD. Therefore the present paragraph yet elaborates on several characteristics of IAD. It models the situation as an action arena. The arena is succinctly in a single sentence described as "participants in positions, who must decide among diverse Actions in light of the Information they possess about how actions are Linked to potential Outcomes and the Costs and Benefits assigned to actions and outcomes"1. The parts of the sentence in red are the seven variables, which characterize the arena. Following methodological individualism, IAD defines a situation by means of its actors or participants. Each actor has one or more social roles or positions. The positions determine the possible actions, which the actor can choose.

Moreover, the actor has access to information thanks to his position. The information tells the actor among others, to what extent he can control the outcomes of the total set of actions. In the mentioned sentence the term "linked" expresses his control. This concept is the most complicated one of the seven variables, and therefore deserves some explanation. Actions are actually an inter-action, because the actors are mutually dependent for their outcomes. The actions interfere with each other. The combined effect of all separate actions is called their aggregation. An example is the election, where each actor can vote. The control of the actor is 1/K, where K is the number of actors. Another example is the negotiation, which is concluded with a collective contract. Here the control is determined by the power, which is available to an actor2.

The IAD terminology refers to the aggregation as a set of transformation functions3. The set of actions can be represented as a game in its extensive form. Indeed the IAD is clearly influenced by ideas from game theory. Note that in game theory an action is called a strategy. The events in the action arena are a chain of successive individual actions. Transformation functios are coupled to the various nodes in the decision tree, which is passed through. The outcomes are the concrete, objective results of the combined action. However, each actor has his own subjective valuation of the outcomes, which are calculated as a personal analysis of costs and benefits.

Each of the seven variables determines a corresponding category of rules of behaviour. Together these rules determine the system of institutions in the arena. There are rules of boundary, which regulate the entry of actors in the action situation. There are rules of position, which describe the available positions, roles or functions. The boundary rules also regulate the access of actors to these functions. The possible actions of an actor are determined by his authority. Therefore his actions are subjected to the rules of authority. The IAD illustrates this with game-theoretic concepts. Namely, the authority rules determine the form of the decision tree in the action situation. In each node of the tree these rules define, what an actor can do4. E. Ostrom refers to the authority rules as rules of choice5. Apparently the authority of a position contributes to the power of the concerned actor6.

The control, which the actor can exert on the relation between actions and outcomes, is regulated by the rules of aggregation. The aggregation is dictated by the institutions, and therefore can not be chosen by individuals. Each node in the decision tree has its own manner of aggregation. For instance, voting can be based on the majority, or on consensus. Sometimes the aggregation is simply the command of an actor7. The spreading of information is also regulated. The information is often tied to a certain position or function. Also interesting are the rules of scope. They restrict the possible outomces. And finally, there are rules of payoff, which regulate the costs and benefits of an actor.

The Ostrom couple presents the dependencies between the seven variables in a flow scheme8. See the figure 1. Your columnist translates this in mathematical formulas. The position pk of the actor k is actually an independent variable. It partly determines the information ik(pk) of the actor k. The power of the actor k can be represented as rk(pk, ik). Note that the IAD does not explicitely include this variable in the situation9. The set of possible actions is sk(pk, ik, rk). The outcome of the actor k is qk(s, f). Here s is the vector of selected strategies, with components sk (k=1, ..., K). And the vector f is the set of transformation functions. The nett utility of the outcome is uk(q, s). Here q is the vector of outcomes. The actor k naturally attaches value to qk, but sometimes also includes the outcomes of others in his valuation. The utility depends partly on s, which represents the process10. The utility can be divided in benefits bk and costs (disutilities) ck.

The theory of IAD is generally applicable, also in complex situations. Nevertheless it is clear, that it copies concepts of game theory. Reversely, studying game theory helps to better understand IAD. For instance, for a non-cooperative game in its normal form with a 2×2 matrix the transformation function is simply the matrix itself11. Note that the IAD is mostly applied to common-pool resources, in short CPR). For such goods there is some rivalry between consumers, so that they differ from public goods. Here the collective-action problem (in short CAP) is not under-production (free riding), but over-consumption of the good. Incidentally, E. Ostrom has yet applied IAD several times to public goods12.

It is worth mentioning that IAD really has the ambition to predict the actions and outcomes in the action arena13. Therefore the word development has been included in the term IAD. Your columnist expects, that IAD can never include all social complexity. Naturally IAD can be used for justifying suggestions for policies. Then the chance of a good advice is yet largest in simple and transparent action arena's. Probably for this reason, Elinor Ostrom has focused her studies mainly on the Third World. Nevertheless, also in game theory the ambition to plan outcomes increases, notably in the social mechanism design14. This has been applied with some success in the development of auctions for renting parts of the electro-magnetic spectrum.

The Gazette has discussed actor-centred institutionalism (in short ACI) in many columns. The policy analyst O. Treib, who has translated Games real actors play in German, has made some remarks, which deserve mentioning15. He states that ACI has originally been developed in order to study self-organizing, incidentally just like IAD. Policy results from the interaction of actors. Sometimes it unfolds in the shadow of a powerful hierarchy, such as the state16. This has the advantage, that a deadlock is less likely. The ACI applications of Scharpf emphasize the motive of personal interest, and pay little atttention to the shared morals. ACI is bad in making predictions, and is mainly used for the description and analysis of policies in retrospect. Game theory is used as a universal language for policy analysts17.

The sociologist U. Schimank notes that ACI does not explicitly pay attention to important social processes, such as differentiation, individualization and rationalization18. Incidentally, this remark also holds for IAD. Such processes unfold in the long run, whereas ACI mainly addresses the short-term dynamics in the constellation19. The idea, that actors can determine their own fate, originates from the Enlightenment20. But institutions are yet necessary in order to make behaviour somewhat predictable. Then actors can develop rational expectations.

Each theory requires an image of man. Your columnist is still impressed by the actor model of Binmore. In this view man is an enlightened egoist, who gives the highest priority to spreading his genetic material. He is a true altruist for his immediate family. But towards others he defends his own interest. Here he takes into account the relations of power, by means of empathy. This is to say, the actor disposes of the capability to be emphatic, so that the behaviour of others becomes somewhat predictable. He trains his innate capability to feel empathy within the family, and by means of self-reflection can also apply it to outsiders. The distinction between altruism and empathy reminds of the mechanic and organic solidarity of Durkheim. Unfortunately the model of Binmore is not yet mainstream. The table 1 presents the nowadays most popular actor models.

| goal | morals | |

|---|---|---|

| individual | homo economicus | homo politicus |

| collective | homo sociologicus | homo sociologicus |

The actor can guide his actions by his goals or morals. And he can have an individual or collective attitude. An actor with an individual orientation acts autonomously. An actor with a collective orientation only accepts reciprocity. He acts just like his environment, and expects this orientation also of others. His behaviour is mechanistic and deterministic. Therefore his behaviour is predictable, but also dismally primitive. Sociology often uses the model of the homo sociologicus, because it wants to explain collective behaviour, at the meso- or macro-level. In the political science communitarianism cherishes this image of man. The reciprocity can refer to the purposive individual behaviour, but also to norms and values. Homo sociologicus in its most primitive form simply obeys collective morals21.

A problem of the homo sociologicus is, that this actor model actually does not explain cooperation. The motive for mechanistic behaviour is unclear. The model assumes the inclination to cooperate as an empirical fact. Moreover, the social institutions do no assume that an actor is a robot, but someone with personal responsibilities22. The homo politicus cherishes his own moral identity. This can deviate significantly from his environment. This model also fails to give much insight in the motives of the actor.

The actor model of the homo economicus, finally, is more attractive, because it can predict behaviour, as soon as the interests of the actor are known. The actor maximizes his utility. Usually a complex model of the homo economicus is applied, where the actor takes into account various costs, for information, contracts, exploring alternatives, and the like. Then the prediction of choices also becomes complex. Besides, it is usually assumed, that the judgement of the actor is subjective, and not objective, precisely due to the complexity. When probabilities of events are estimated subjectively, and possibly inaccurately, then behaviour is no longer entirely rational.

The actor model of the homo economicus allows to study the motives for cooperation. It becomes rapidly clear, that in many situations the personal interest requires cooperation. These are especially situations, where the mutual transactions are repetitive. Then the homines economici must coordinate their behaviour, because none of them wants to be exploited by the other(s). A number of methods have been discovered, notably in game theory, which lead to the coordination and orchestration of actions.

The most important path towards coordination is establishing an individual reputation. The actor signals by his repetitive trustworthy behaviour to the other actors, that he has no inclination to exploit. He resembles the stereotype of the trustworthy actor, because this serves his personal interest in the long run. The other actors trust him on rational grounds. Game theory models this with the caricature of the tit-for-tat strategy. Besides, this strategy illustrates an alternative manner of coordination, namely the sanction. Cooperation pays, because a profitable interaction can be repeated. So the most important sanction is ending the interaction! Each actor must take into account this threat. Sanctions are even more powerful in groups, because third parties can also punish exploitation. But since a third party, who intervenes with punishments, incurs some costs, this is not always in his own interest.

Furthermore, cooperation is possible when all involved actors let their behaviour be guided by an external signal. Consider for instance an external expert, who publicly makes recommendations for certain market transactions. Game theory calls this a correlated equilibrium. Both the punishment and the external signal can have the form of an institution. Institutional limitations of behaviour can aim at goals or at morals. Sometimes the distinction is vague, because for instance an actor can value sound procedures. Institutions, heuristics and routines can reduce the transaction costs. This explains among others, why sometimes the hierarchy is preferred above the market. There the exchange is less beneficial than rules. Sometimes coordination is possible by means of a focal point. Them the logic of the situatie dictates a certain behaviour23.

Apparently a homo economicus yet often succeeds in coordinating actions. Sometimes a group wil engage in a transaction, and here accept some exploitation by outsiders. This happens for instance in the production of a public good. The number of alternatives for transactions evidently increases strongly, when the negatively affected actors are compensated for possible damage. And in a society with a mix of actor types the homines economici can be coerced into cooperation by the homines sociologici and homines politici. And perhaps the most important institution is the constitution, which can dictate the mutual cooperation as a social contract. The constitution is formulated behind the veil of ignorance, where the collective and the personal interest coincide.

Note that the boundary between the individual and collective orientation of actors is fluid. For instance, the stereotype actually refers to a group. Thus a certain professional group as a whole can acquire a certain reputation. In principle the homo economicus can base his decisions on such a stereotype. Then he rationally estimates the probability, that a member of the professional group resembles the stereotype24. But such a judgement can rapidly become subjective. In the same way the actor model of the homo sociologicus can be used. He bases his decisions simply on the norm, that the whole professional group resembles the stereotype. Infringements on the norm are punished.

Apparently there is some ambiguity in the actor models, which reminds of the model of social exchange, invented by the sociologist J.S. Coleman. This allows the exchange of concrete outcomes (such as goods) and symbolic outcomes (such as status). The value of status is subjective, and perhaps emotional. Such an exchange is not along the lines of the homo economicus. Cooperation can be bought. The same can be said about the dedication of actors to their group, which according to the economist P. Frijters is based on a complex psychic exchange. The dedication is caused by de-individuation, which undermines the personal preferences. Such a process reduces the homo economicus to a fragile being25. These models illustrate, that the actor model of the homo economicus is not applicable in all circumstances.

Already years ago a column studied the group behaviour from an individual (pychological) and collective (sociological) perspective. Individual actions cause a dynamics, which can change the collective order. This is particularly true for the economy. Moreover, the economic system creates its own sphere within society. But not only the economy isolates itself. A previous column presented a model of the sociologist H. Ganßmann, who builds on the theory of K. Polanyi. Here the economy, the state and society coexist. Already several decades before, Weber had identified many sub-systems in society. Each sub-system has its own function, and its own logic (norms and values)26. This is called a system-differentiation. The notion, that such sub-systems exist, even stimulated the idea of planning, which since years has attracted attention in the Gazette.

Incidentally, differentiation is not limited to sub-systems. Durkheim elaborated on the differentiation of roles, which people assume in society27. The most well-known example is evidently the division of labour. All these forms of differentiation are related to the rise of modernism. This process is dynamical and progressing. At the same time religion loses its function as shared and uniting morals, both between systems and between roles. Sociologists such as Marx, Durkheim and Polanyi were afraid, that as a result of differentiation society would disintegrate (alientation, anomie). Obviously, the institutional analysis (ACI, IAD) is also aware of differentiation, and takes into account institutions. But here it is rather hidden, and merely present implicitly, for instance in the configuration of IAD. The present paragraph wants to clarify differentiation by means of the actor-institution frame.

The explanation is fairly simple for the differentiation of roles. For, in the IAD the action situation is determined by the positions P. So here differentiation is realized by means of the allocation of positions to actors. Furthermore, both ACI and IAD allow for the nesting of constellations, for instance in various levels of regulation. This implies, that a constellation can often be divided in sub-systems. But this is not really a theory of systems differentiation. After the Second Worldwar the Americans sociologist Talcott Parsons has developed a profound and complicated systems theory28. It is worthwhile to investigate, what it implies for the actor-institution analysis. According to Parsons differentiation means, that wherever possible a task or function is executed within its own sub-system. This increases the productivity of the execution of tasks. In this manner the social performance is improved29.

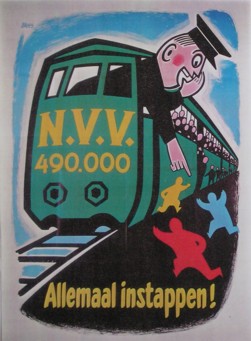

For this reason the systems theory of Parsons is also called structural-functionalism. The theory is deductive30. This is to say, it consists of assumptions and hypotheses. Each system has an input of resources, and an output. When the production is continuous, then according to cybernetics the output can be measured, and subsequently the measured value is put in the system itself (feedback). When the measured output is not satisfactory, then the system can adjust its internal production towards a better result. Thus according to Parsons each (sub-)system has at least the task to determine a target value (G, of goal), and to adjust the production, when necessary (A). Besides, the system must dispose of an internal order. There are rules, which must guarantee the integration of the system components (I). And the system must have an internal latent culture or morals, which gives meaning to its own existence (L).

This is called the AGIL scheme31. Each of the four tasks is functional for the concerned system. For instance, society can be interpreted as a system. Then the four systems are the economy (A), politics (G), the administration (I), and the moral formation (L)32. In the terminology of Parsons L is equated to culture. Next each of the four sub-systems can again be divided in sub-systems. Consider for instance the economic system. There A is the capital market, G is the commodity market, I is the entrepreneur, and L is the morals of markets33. Parsons does not precisely explain, how the sub-systems form. But since differentiation leads to a better performance, it is suspected that it is an evolutionary process. Successful systems are imitated by others. On the other hand, politics could purposively organize differentiation. Then it must carefully reflect on the possible side-effects34.

Now consider again the cybernetics of the system. There is a certain hierarchy among the various sub-systems35. The culture (L) forms the highest layer in society. Parsons even calls himself a believer in cultural determinism! Here the informal institutions and rules are established. They are used to derive the formal rules, which are propagated by the administration (I). These rules are not only formulated by the state, but also by various social organizations. They change only slowly. At a lower level the policy goals are formulated (G), as far as the rules permit this. Finally, in the lowest layer the system is adapted in such a way, that the goals can be realized. Apparently the AGIL scheme is part of the feedback loop of the system. This is shown schematically in the figure 3.

The figure 3 shows, that there is a hierarchical interaction between the sub-systems. But the systems theory of Parsons acknowledges, that the interactions between two sub-systems is reciprocal (like, incidentally, in each hierarchy). This is called the double interchange36. The interaction between the sub-systems only has the aim to guarantee, that the total system remains in equilibrium. Some integration of the sub-systems is indispensable. Apart from this necessary interaction the functionality implies, that the sub-systems are autonomous. Parsons states that the most important means of interaction are money, power, influence and morals37. Since the social differentiation leads to a better performance, it is an indispensable part of progress. Parsons calls it a universality38. This also illustrates that Parsons has an optimistic belief in progress.

It is interesting, that according to systems theory the society converges to an equilibrium. Following this description of systems theory, now the implications for ACI and IAD can be studied. Systems theory is very relevant for the action configuration, namely the rules, the culture and the material circumstances. Systems theory emphasizes the dynamics of the configuration. The aim to improve the performance implies a progressing differentiation of the configuration. This evolutionary process is obscured in ACI and IAD. There the systems are part of the institutions, which can apparently differentiate themselves. An analyst must take this into account. Furthermore, systems theory underlines, that decisions are not made in a linear process, but as loop. Note that the policy cycle is indeed a system with feedback.

In ACI and IAD the constellation or action arena models the interactions between the actors. These interactions are excluded from systems theory. The absence of the action situation in the systems theory of Parsons implies, that the social motives are naturally moral, so that at least at the macro level the personal interest is unimportant39. Incidentally, Parsons invented already before his systems theory the theory of individual actions(unit act), which do hold at the micro level. The unit act is a scheme of actions. Each action is based on the morals (L) and goals (G) of the actor, as well as on the situation40. Here the clear assumption is made, that the behaviour of the actor is determined by culture. In this sense Parsons appreciates communitarianism. But yet Parsons also takes into account the specific situation.

On the other hand, ACI and IAD are more than a systems theory. Not all constellations or action arena's are systems. Sometimes they support the double interaction between the various sub-systems41. The action situation can simply be a network. Furthermore actors can start a differentiation, which is in their own interest, but not in the general interest42. This undermines the vitality of the system, but this becomes clear only in the long term. Parsons believes, that the increasing dependency due to functional differentiation leads to a natural incentive to integrate43. Incidentally, since 1966 and the rise of the New Left the systems theory of Parsons has become controversial. Analytically a number of paradoxes are observed in this theory44. Your columnist still believes that systems theory is usable, although the criticism must be taken to heart.

The optimism in the systems theory of Parsons fits poorly with the social problems of the sixties and seventies. The western societies increasingly became confused. An important negative factor was the Vietnam war, which discredited the North-American government45. The enormous costs of the war, and subsequently the oil-crises, caused economic recessions, which shook the belief in progress. But shortly after Parsons, the German sociologist N. Luhmann developed a systems theory, which was better adapted to the pessimistic spirit of the time. Whereas Parsons explains the differentiation with the need for functionality, Luhmann sees the cause in social pluralism. The hallmark and reason of existence of a sub-system are its culture and internal morals. In other words, the normative expectations of actors are bound by their system46.

According to Luhmann the (sub)-systems are primarily dedicated to their own survival. Notably, a system wants to maintain its own logic, inner will or morals. The crux is not the division of labour, as claimed by Parsons. The system must naturally adapt to external influences, but the goal is the continuation or spread of the system's morals. There is self-reference and self-construction, which is called autopoiesis by Luhmann. Each system has a single dominant value, the so-called binary code47. Luhmann supports his theory with the group theory of social psychology. He notably refers to the phenomenon of attribution48. Since each system has its own binary code, the world is explained with different perspectives. There is no absolute truth49.

Contrary to Parsons, Luhmann denies the existence of an all (sub-)systems encompassing society. He calls this differentiated society poly-contextural50. There is no meta-constitution, as is assumed by the IAD51. Luhmann clearly is a communitarian. The absence of truth has the surprising consequence, that in itself an action is devoid of meaning. It can not be justified on objective grounds. The action can only obtain meaning, when it is translated subjectively in an interpretation. It must be placed in a certain perspective52.

Luhmann tries to find the origin of differentiation, and therefore of systems, in the social evolution, just like Parsons. The sub-systems are mainly needed for reducing the internal complexity, and thus give the actors something to go on53. However, the evolution occurs in the systems themselves. This is different with Parsons, who expects integration as a result of culture. The evolution is naturally path-dependent, but the development of society as a whole is still unpredictable. At the macro level the equilibrium is absent. The differentiation does increase continuously, notably because the adaptation to the external influences dictates this.

The closeness of the systems in the theory of Luhmann is a scenario of doom, which has elicited criticism. For, empirically it turns out that societies develop in a fairly harmonious manner. There is no continuously threatening disintegration. Luhmann tries to explain the stable path of development by an increasing material scarcity54. It at least forces the system to accept efficiency as an additional value, besides the binary code. Moreover, due to scarcity the systems are incited to engage in self-reflection, and therefor to exhibit some empathy for other systems.

Luhmann definitely denies, that the political system is capable of controlling the other systems. His idea is an abstraction, which is controversial. For instance, the policy analyst F. Scharpf states, that systems function in the shadow of the powerful state55. This controversy can also be formulated in the following way. Many policy analysts believe, that the social order is a public good is. According to Luhmann this good can not be established. The social system as a whole remains sub-optimal. The sub-systems themselves are ordered, and benefit from this. But the order in a sub-system creates damaging external effects for the other sub-systems.

Your columnist sees a clear difference between the systems theories of Parsons and Luhmann. The theory of Parsons is deductive. For centuries it turns out that empirically the division of labour advances. Sub-systems emerge in order to improve the productivity. So here the order of a sub-system is also a public good. Thus the argument of Parsons assumes an instrumental rationality. The advantage is, that the theory allows to make an objective analysis, because production can be measured. Unfortunately there are sometimes external factors (wars, economic crises, pandemies), which undermine the assumption of a rising productivity. The theory is poor for such periods.

The theory of Luhmann is inductive, and relatively independent of external factors. Sub-systems emerge due to the disappearance of all-encompassing morals, which results in pluralism. The argument of Luhmann is based on value rationality. It is related to institutionalism. But the disintegration of society can not be observed. The assumption, that the systems logic (inner will) determines the internal activities, naturally has important consequences for the actor-institution analysis (ACI, IAD). For instance, the enforcement of rules by a third party is hardly an option. Your columnist believes that the assumption of closed systems is a dubious abstraction. Perhaps the theory of Parsons yet deserves a second chance in the present time of globalization, which is characterized by strong regional growth of the economy.

The policy analyst P.A. Sabatier presents a systems theory, which combines the IAD and the theory of Luhmann. He calls it the advocacy coalition framework (in short ACF)56. The ACF is only applicable to specific constellations, namely the action arena's, which must formulate policies within sectors. It provides the policy analyst with a frame of thought. Just like Luhman, Sabatier bases his actor model on group theory. A groups disposes of a moral core of fundamental convictions and expectations (deep core beliefs, or in the words of Luhmann: an inner will). In the ACF the groups have mutual biases, and these even result in demonizing each other (devil shift)57. So the actors are boundedly rational. Contrary to Luhmann's view, these expectations are not universal for the sub-system. For, within the system coalitions form, each with its own expectations.

The expectations of the group concern the whole social life. The sub-system is just a part of life. The concrete details of the expectations of the group within the sub-system are called the policy core beliefs. The coalition in the sub-system consists of groups with common policy morals. Although Sabatier acknowledges, that motives are mixed, apparently the groups do not primarily seek personal advantages (instrumental rationality)58. The policy morals of a coalition are very stable. Usually the sub-system is dominated by a single coalition, so that the sub-system indeed has a stable will. Change occurs mainly in the policy instruments, which are called by Sabatier the secondary aspects.

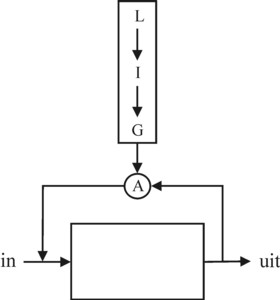

The sub-system describes in essence the policy cycle. Therefore it has a strong resemblance with the scheme of the IAD and ACI. This is illustrated in the figure 4 59. The ACF includes mediators in the constellation, besides coalitions. In the figure 4 the decision about the policy morals is followed by the policy formulation concerning the secondary aspects. The execution of the policies is followed by a feedback to the system. The ACF sees the feedback mainly as a learning process. However, later the possibility of renegotiations is also added to the scheme. Nevertheless, the sub-system itself is very stable and conservative. Possible changes must come from external incentives (just like Luhmann argues). The interaction of the policy cycle with the environment (other sectors, the state, etcetera) is now well known from the ACI and IAD.

The ACF distinguishes between two factors in the external influences, a stable and variable one. The (relatively) stable external factor consists of the institutions, culture, and the physical environment. The institutions limit the options of the actors in the sub-system60. For instance, in European corporatism there is a lot of bargaining. And in the pluralism of American federalism often log-rolling is used. The variable external factor includes changes in other sectors and in politics, as well as putting problems on the agenda by the news media. This factor determines the quantity of means, which the actors in the sub-system receive. The external changes are evidently restricted by the constant external factor. Besides, the sub-system itself somewhat affects the variable external factor (again a feedback, but now external).

The ACF calls changes due to the environment an external shock. Internal learning can also occur as a shock. Then the policy morals of the dominant coalition are undermined. Sometimes it is not simple to identify the policy morals of a group. The ACF hopes, that in the future the social network analysis (SNA) can remedy this. In addition to the presented frame of thought the ACF also has a number of empirical (deductive) hypotheses with regard to coalitions, policy changes, and policy learning. It concerns statements such as: "Problems for which accepted quantitative data and theories exist are more conducive to policy-oriented learning across belief systems". Your columnist can not judge the analytical value of the hypotheses. Their value must be proved in practical applications.

The paradigm of the advocacy coalitions has several disadvantages, which limit its applicability. Although the ACF allows for mixed motives of the groups, it yet strongly emphasizes the value rationality, at least in the consulted sources. This neglects the effects of strategic actions. The strong motive of opportunistic rent seeking is not included in the analysis. But without rent seeking rational actors have little incentive to join their preferred coalition, because of the costs. They prefer free riding61. Furthermore, note that Sabatier adheres to positivism62. An absolute truth exists. However, his frame of analysis corresponds to the frame of Luhmann, which is based on post-positivism. Therefore the ACF makes an ambiguous impression.

It is interesting to compare the ACF with the IAD. The IAD is universally applicable, namely in each action arena. It takes into account the preferences of the actors, but these mainly refer to performance and the material interests. On the other hand, in the ACF the preference is dictated by morals, and this even endogenously stimulates the formation of coalitions. Thus the inner stability of the sub-system is actually assured, and requires no attention. Then change is external. The IAD has once been designed in order to analyze self-organization, whereas the ACF is more oriented towards hierarchical policy networks. To be honest, your columnist finds it difficult to see the added value of the ACF in comparison with the IAD63.

Systems theories assume that a system is capable of controlling its own performances (output or outcome). It is no coincidence, that the systems theories prosper in the period after the Second Worldwar, when there was a strong reliance on social planning64. The planning approach already started in the interbellum, as a reaction to the Great Depression since 1929. At the time the sociologist Karl Mannheim provided for an analytical basis65. Planning is modeled by means of cybernetics. The experiences with large-scale planning are disappointing, also in the public administration. Therefore after 1980 there is a renewed interest in actor-centred models (AGI, IAO)66. Luhmann rejects this approach. For, according to him the actors are embedded in their own system, and can not act or bargain freely. Notably, the political system can not steer, due to the social poly-contextuality.

The German sociologist H. Willke believes, that corporative actors do make mutual compromises, also beyond their own system67. Thus for instance the political system can establish institutions, which regulate the self-organization of other systems. The state checks, that the systems serve the general interest. This is also the view, which is propagated by the new public management (in short NPM). The sub-systems engage in contracted performances. Due to the personal responsibility the execution can become efficient. A more radical view is the idea of network management, where the state is merely a partner within the network. The sub-systems legitimize themselves68. However, then the transparency is minimal. This evidently excluded the civilians as voters. Besides, such systems can not realize integration and central coordination. This is undesirable69.

Your columnist has acquired a collection of socialist literature, dating from say 1900 until the present, which together fill several bookcases. During the early years of the Gazette these books were an important source of information for writing columns. At the time your columnist believed, that the present society can only be explained objectively, when the actual situation is viewed in a historical perspective. In retrospect this opinion was perhaps based on an unwarranted suspicion towards the modern science. For, old ideas naturally live on in the present literature, at least, as long as they are sound. Therefore in the past years your columnist began to consult more recent books. But, nostalgic feelings can never completely be given up. Therefore this paragraph yet describes several ideas about the systems theory from a historical source.

Already 15 years ago your columnist read the voluminous book Marxistische Philosophie, which in the party schools of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik were used as textbooks of the Marxist-Leninist philosophy70. The systems concept is universal, and a philosophical category (p.218). The system consists of elements, and their mutual relations (218). For instance, the historical materialism defines the society as a system, which includes the classes as its elements (219,222). The element itself can again be a system (219). Therefore there is a hierarchy of systems (223). The relations between the elements define the structure of the system (220). For this reason marxism studies the social class structure (228) According to the dialectical materialism all systems are dynamic (219). The elements interact with each other and with their environment (219).

Moreover each system has a function (220). When various systems have the same function, than in the evolution the system with the most effective structure will persevere (221). Even capitalism succeeds in moderating the economic crises (221). In principle any system is open, with an input and output (225). However, sometimes the environment hardly affects the system, and then the closed system is a good approximation (225). See the dynamic growth model of Marx. The choice of the system boundary is usually somewhat arbitrary (226). The same holds for the environment, which interacts actively with the system (226). For instance, the climate is not included in the environment of the labour class as a system (226). A system with internal feedbacks is a control system (227). When the control system compensates for disturbances, then it seems to pursue a goal (227). When the system always reacts effectively, then it is learning (227).

The essence of the capitalist system is determined by its invariant properties (374). An example of an invariant is the contrariety of the private property and social labour (374). The essence of the system is its quality (375). In addition, the system is characterized by the number of elements, so by quantitites (377). But these elements naturally have their own quality (378). However, when the quantities in the system change too much, then its quality will also change (379). For instance, the socialist system has another quality of productive relations than the capitalist system (379). The productivity, the satisfaction and the culture are qualitatively better in socialism (379). This can be shown empirically by for instance measuring the production (380).

Moreover capitalism is not stable (382). The control mechanism of the system does not succeed in compensating the quantitative changes by means of feedback (381). The concentration of private property increases the social contrarieties, so that in the end the society becomes revolutionary (382). The system quality changes into socialism, and destroys the capitalist system (412). Necessity and coincidence interact in a dialectical manner (410). Therefore this is called a dialectical jump (383)71.