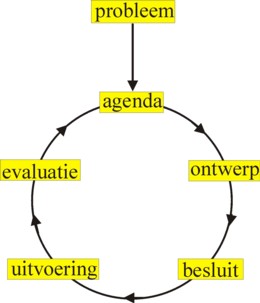

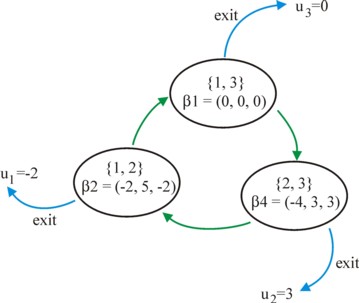

Figure 1: Policy cycle

The social choice theory offers models of decisions, which are relevant for the public administration. For, the decision is a part of the policy cycle. Notably the social choice theory studies the formation of coalitions. The coalition game can have stable outcomes, which are in the core. It is conceivable, that the actors in the coaliton can transfer utility. Often the actors will exchange votes (logrolling). The Shapley value is a way to integrate morals in the social choice theory. Finally the applicability of the social choice theory will be discussed.

A previous column has described four policy models in the public administration, which have as their starting point respectively the rationality, the political struggle for power, the social culture, and the institutions1. This distinction is clarifying, but the terms deviate somewhat from the conventions, which are used by the Gazette. In the economic perspective the policy models refer to respectively the plan, the power, the communication, and the institution. In this row the communication is somewhat different, because it is actually more a skill than a social phenomenon. Yet it is essential for the success of policies. Managers must be able to convince, motivate, and be experienced in making propaganda. A decision is only executed, when it has sufficient support of all concerned. Until now the Gazette has usually ignored the effect of communication2.

In the traditional policy approach (say, the plan-model and the power-model) a certain policy programme is introduced as a reaction to a social problem. It is commonly assumed, that the policy can be interpreted as a linear succession of phases. The decision is just a part of the whole. Moreover, policies are never complete, because the environment is dynamic. There is feedback from the society, and this results in continuous learning. Then the linear chain changes into a learning cycle, like in the model of Kolb. Therefore the policy cycle has the form of the figure 1. However, a striking hallmark of the policy cycle is, that the learning process is affected by conflicts between interest groups. Then the interpretation of the cycle of Kolb has two components, namely the political struggle about the policy agenda, and the design of the policy programme3.

Almost all models in the Gazette assume, that the actor is a homo economicus. He decides in such a manner, that his utility or well-being is maximized. However, the well-known policy analyst Herbert Simon states, that decisions are based on a bounded rationality. In practice the maximization of utility is simply not possible. The homo economicus becomes modest, and is satisfied with decisions, which minimize the risks of loss4. Such decisions can use a logic of goal realization, or a logic of appropriateness5. Appropriateness implies, that the dominant norms and role expectations within the organizations are satisfied. The corresponding image of man is the homo sociologicus. These two types of logic can be related to respectively the Weberian instrumental rationality and value rationality.

In the logic of appropriateness the actors aim for a satisficing solution of the problem. The context of the decision is included in the evaluation. Often such a solution is incremental, because then the group interests will not be hurt significantly, and the risks of a disastrous failure are small. There is a continuous evalution, and the policy evolves. See the institution model of policies6. In this regard the approach of new public management (in short NPM) is two-edged. On the one hand new public managent allows to rapidly react to external threats. On the other hand, innovative entrepreneurship is naturally risky. Decentralization of the policy decisions is a manner to maintain control in social pluralism7. This view is for instance embodied in the garbage can model.

Decentralization implies, that the ambition of the central plan (plan-model) is abandoned, or at least has a lower priority. More room is given to the competition between interest groups. The agenda is determined by policy networks. Here the power model and the communication models of policy are applied. Economists and sociologists have developed the rational choice paradigm, with applications aiming at social decisions (social choice) and public policy (public choice)8. The actors (individuals and organizations) primarily promote their own interest. All concerned groups are rent seeking. Models usually translate this interest in terms of income. In principle moral or psychological interests can also be taken into account, but this makes the interpretation of the model less tangible. Thus the power of the citizens can be studied, or even of a coalition of politicians and agencies (Leviathan model)9.

When the state prefers decisions by means of network management, then this is called public governance10. Use is made of partnerships, and of contracting11. The state negotiates with the concerned groups, and compromises. The means of the concerned actors are bundled. Thus the decision is made by a coalition of groups. So within this coalition there is cooperation. Nevertheless in such a network entrepreneurship has an added value12. The management of policies becomes polycentric13.

Policy formation by means of networks is an attempt to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of policies. However, it can also be advocated on moral grounds, namely that it furthers the participation of citizens, and therefore reinforces the democracy. This does introduce the danger, that in this way the active citizens obtain an excessive amount of power.This would affect the legal security of the citizens. And the social benefits are vague14. The argument for participation is mainly important in the communication model, and in the institution model as well. Networks in the institution model can have the form of corporatism. In (neo-)corporatism the state transfers power to some interest groups15.

The science of public administration addresses the environment, where policy is formulated. This includes the procedures, the pertinent factors, the conditions, the point of decision, and the chosen instruments. But evidently a coalition of actors must also emerge, which is prepared to be the owner of the policy problem, and to decide about the best solution. In public administration little research is done with regard to the factors, which determine the composition of this coalition. This question has been addressed by the social choice theory.

The decision theory in the public administration pays little attention to the ideas of the social choice theory, which is methodologically related to economics. Here your columnist wants to try to fill the lacuna. A column of three years ago used an exchange theory in order to model decisions. But usually the social choice theory applies game theory to policy problems. However, the public administration sometimes also describes the policy decisions as a game16. Each actor k in this game (with k = 1, ..., K) makes a choice from his set sj(k) of behavioural strategies (j = 1, ..., J(k)), tailored to the given situation. In principle the number of strategies J(k) of each actor k can be infinitely large. Moreover, j could be a continuous variable within the interval [1, J(k)]. The combination of strategies leads to a policy decision.

Thanks to the decision the actor receives benefits in quantities xn(k) (n = 1, ..., N). So there are N types of benefits. Each type n can be material, but also in kind, for instance information or a good reputation. The actor k must estimate, what the value of these benefits is for himself. Thus for instance money and reputation are mutually compared. It seems odd, but it is possible according to the model of Fao and Fao17. The decision determines the totally available quantities xn of each type n, as well as their distribution Σk=1K xn(k) among the actors.

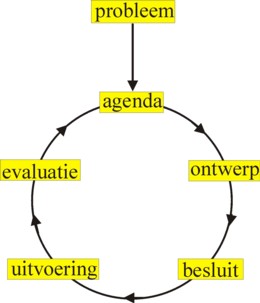

The evaluation of the actor is naturally based on his preferences. In the rational choice paradigm the preferences of the actor k are represented by the utility function uk(x(k)), where the vector x(k) consists of the elements xn(k). Apparently the utility vector u is in the end the criterion for selecting a decision. Therfore the social choice theory primarily studies the distribution of utilities, and not of benefits18. It has just been remarked, that the decision is the result of the strategies sj(k), which the K actors use. Therefore the set of all strategy combinations {sj1(1), ...., sjK(K)} (with jk=1, ..., J(k)), which is the set U of utility possibilities u. As an illustration the figure 2 shows the outer boundary of such a set U for K=3 19.

The figure 2 assumes, that all three actors participate in the decision about the policy. Each one contributes with his own means to the policy formation. But except for this there is not yet a cooperation and coordination between the actors. Each actor maximizes in isolation his utility, by means of his strategy. Note that in practice a large number of points u within U will most likely not occur. For instance, in the figure 2 the actors 2 and 3 will simply not select a strategy, which gives the actor 1 much more utility than they acquire. Therefore the final decision u* will probably lie somewhere in the middle on the outer layer. Only when the actor 1 has a large ascendancy of power, he can appropriate all benefits. Then he barely needs the actors 2 and 3 for the policy formation.

However, the present column discusses the cooperation of actors. In it simplest form this is a coalition C of two actors. They can benefit from C, because they can coordinate their strategies in this manner, so that another decision is possible than without cooperation. For instance, the coalition C, consisting of C = {1, 2} can enforce a decision, which increases u*1 and u*2. This hurts actor 3, so that his u3 diminishes. Actor 3, the loser, will yet try to maximize his utility u3 in the given situation20. As an illustration of this phenomenon the table 1 (originating from the policy analyst P.C. Ordeshook) shows a game with three actors, where each actor k disposes of two strategies s1(k) and s2(k) 21. So the available strategies are not continuous, such as in the figure 2, but discrete. The cells show the utilities (u1, u2, u3) of each strategy combination. The table 1 forms the basis of a network analysis22.

| s1(3) | s2(3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1(2) | s2(2) | s1(2) | s2(2) | |

| s1(1) | 57, 50, 15 | 0, 60, 35 | 55, 20, 0 | 30, 30, 40 |

| s2(1) | 70, 55, 30 | 0, 90, 60 | 50, 0, 80 | 20, 60, 70 |

Game theory calls the table 1 the normal form of the game. The outcome (30, 30, 40) is the result of the strategy combination (s1(1), s2(2), s2(3)), and is the so-called Nash equilibrium. No actor {k} can unilaterally take a decision, which yields him a higher outcome. His first preference (respectively 70, 90, and 80 for k = 1, 2 and 3) is blocked by the other actors. It is also not advantageous for an actor k to form a coalition {h, k} (with h, k in {1, 2, 3}). Consider for instance the coalition C = {1, 2}. Thanks to C the actors 1 and 2 can block outcomes, which are favourable for actor 3. The actor 3 naturally does keep his freedom of acting sj(3). Now he must undermine the coalition in negotiations by threatening the two actors with punishments.

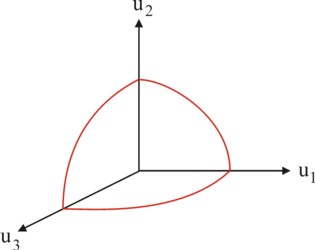

C can choose from four strategies sj(C) = (s1(1), s1(2)), (s2(1), s1(2)), (s1(1), s2(2)) and (s2(1), s2(2)), which yield respectively μj = (u1, u2) = (55, 20), (50, 0), (0, 30) and (0, 60) with certainty. Note that these are the minimum outcomes for the coalition, irrespective of the strategy sj(3) 23. However, there is a chance, that the actor 3 selects a strategy, which makes the outcome for C rise above the minimum. The behaviour of the actor 3 is not amenable to an exact analysis. Nevertheless, in the following some comments will be made about this aspect.

Apparently the actors 1 and 2 never have a mutual benefit from μj. The Nash equilibrium E = (30, 30) remains attractive. Nonetheless, the coalition C can yet be worthwhile. Namely, it can switch between the strategies sj(C) with a fixed frequency. In this way a mixed strategy σ(C) results. An example of a mixed strategy is

(1) σ(C) = p × s1(C) + (1 − p) × s4(C) = p × (s1(1), s1(2)) + (1 − p) × (s2(1), s2(2))

In the formula 1, p is a real number in the interval [0, 1]. Note that in this approach a choice is made between an infinite number of strategies, just like in the figure 2. Now the certain outcomes in the formula 1 are μ1,4 = (u1, u2) = p × μ1 + (1 − p) × μ4 = p × (55, 20) + (1 − p) × (0, 60). Simple calculations show, that for 6/11 < p < 3/4 the coalition receives more utility than in the Nash equilibrium (30, 30). Other mixed strategies than σ(C) are naturally also possible, but these have a lower yield. This is shown in the figure 3, where the four "pure" outcomes μj are drawn, together with the mixed outcome μ1,4 (red line).

The preceding argument yields new insights in the decisions about policies. It is worthwhile to formulate this approach in general terms. For this, the application of mathematics is convenient. It is said that a game has its characteristic form, when there is a set of K actors, and a (mathematical) rule V, which connects each coalition (subset) C in K to a set V(C) of utility possibilities. The rule V(C) is called the characteristic function of C 24. As an illustration, the figure 3 shows such a set V({1, 2}). It has been coloured yellow in the figure 3. The set V({1, 2}) not only includes the red boundary μ1,4 of utility possibilities, but also all points with lower values u1 and u2. The rule V can also be applied to all other conceivable coalitions ({1, 2, 3}, {2, 3}, {1} etcetera), and then always yields a corresponding yellow area of utility possibilities.

It is instructive to again compare the figures 2 and 3. The red contour in the figure 2 shows all possibilities U = {u} in absence of cooperation. The figure 2 suggests, that the actors 1 and 2 can benefit from a decision, which reduces the utility of actor 3. However, without cooperation actor 3 will block such decisions by means of his strategy. The actors 1 and 2 must mutually form a coalition in order to limit the choices of the actor 3. Then it is still uncertain, whether the actors 1 and 2 will both benefit from the coalition. In the figure 3 they do succeed, thanks to the mixed strategy. Then the analysis does not study U, but a set V(C) of certain outcomes. However, coalitions in a game are not by definition beneficial. Sometimes the actor 3 can select sj(3) in such a manner, that the set V({1, 2}) becomes unfavourable. Then the 3 actors must check, whether another coalition does yield benefits25.

In the same way that the Nash equilibrium of a game is interesting, it is also useful to find stable utility vectors u within the set U of utility possibilities. For, in a stable outcome it is no longer necessary to negotiate, form coalitions, or influence the policy agenda. The actors no longer feel the need to change their strategies. The set Γ of all these stable utility vectors is called the core of the game26. This can also be formulated in an abstract manner. Namely, suppose that there is a game with characteristic form (K, V), then the core Γ consists of the vectors u in V(K), which can not be blocked by any coalition C. A coalition will block a vector u, as soon as a vector w in V(C) exists, which satisfies uk < wk, with k in C 27. In this case it is said, that w dominates over u 28.

As an illustration of these definitions, consider again the game in the table 1. Without cooperation the actors select (30, 30, 40). The assumption is, that mixing strategies is not allowed for the coalition with K=3. In other words, suppose that the function V, applied to the grand coalition {1, 2, 3}, simply reproduces this table29. Then the coalition {1, 2, 3} will also select (30, 30, 40). But it has just been shown, that V({1, 2}) contains vectors wk > 30 for k=1, 2. Therefore this coalition will block the outcome (30, 30, 40). However, the coalition reduces the outcome for actor 3 to w3 < 40. Therefore actor 3 will not cooperate, and his strategy is undetermined. The vector w is certainly not in V(K). Apparently in this case the core is empty. It is worth mentioning, that (30, 30, 40) does form the core, when the outcome for the strategy combination (s2(1), s2(2), s2(3)) in the table 1 is replaced by u = (20, 10, 70) 30.

This illustration shows, that a game without core is unstable. The component 3 of the vector w is undetermined. The game of the table 1 gives an interesting illustration of this31. Suppose that the utility value u3 remains valid, even after the coalition C = {1, 2} is formed and it applies the mixed strategy of the formula 1. Then it is rational for the actor 3 to prefer s1(3). However, then the actor 1 gets a preference for the pure strategy s2(C) = (s2(1), s1(2)). And the actor 2 now prefers the pure strategy s3(C) = (s2(1), s2(2)). Subsequently, the actor 3 will change his view because of the new choice s2(1), and get a preference for the strategy s2(3). Etcetera. In practice this means, that the 3 actors are engaged in a continuous negotiation32.

Unfortunately games with a core are sometimes also not determined completely. In some games the core can be entered by means of various, mutually different, coalitions. Therefore, despite the existence of the core, it can not predicted which coalition will be formed. Only the outcomes u can be calculated in advance. Policy analysts believe that this is a serious defect of this type of game theories, because in practice usually only the coalitions are observable33. It is difficult to measure outcomes. For instance, concessions and obligations sometimes only have effects in the long term.

| β1= −,−,− | β2= +,−,− | β3= −,+,− | β4= −,−,+ | β5= +,+,− | β6= +,−,+ | β7= −,+,+ | β8= +,+,+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| actor 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | -2 | 6 | 3 | -1 | 4 |

| actor 2 | 0 | 6 | -2 | -1 | 4 | 5 | -4 | 3 |

| actor 3 | 0 | -2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | -1 | 5 | 3 |

As an illustration the table 2 shows the utility values u of K=3 actors, who must vote with regard to 3 policy proposals34. This is the game in its normal form. A policy analyst wants to know which coalition is formed, and which policy is selected. Both the coalition and the policy are determined in negotiations35. There are 8 possible outcomes βn (n = 1, ..., 8) of the vote. Each βn indicates which proposals have been accepted (+) or rejected (−). Obviously a coalition of 2 actoren always wins the vote36. The coalition {1, 2} has as Pareto optimal outcomes β2 and β5. For {1, 3} they are β3, β5 and β8, and for {2, 3} they are β2, β5, β6 and β8. Apparently only β5 is Pareto optimal for all coalitions. The corresponding outcome u = (6, 4, 2) is not dominated by any vector. Apparently this u is the core Γ. In this situation the question of the policy analyst is not answered completely, because the core can be entered by different coalitions.

Furthermore is must be remarked, that the phenomenon of the core is only poorly confirmed by experiments. Ordeshook mentions a laboratory study with test persons, where merely 47% of the experiments entered the core as the result of the negotiations37. In the concerned study the reason was, that each actor k mainly tried to agree on the outcome with his highest uk (in table 2: β5 for actor 1, β2 for actor 2, and β7 for actor 3). Thus the attempt to enter the core fails. Ordeshook calls this strategy a heuristic. The aim of the heuristic is to limit the transaction costs. It may evidently be hoped, that for really important proposals the actors will act more rationally. Nevertheless, Ordeshook concludes, that institutions such as voting procedures, agenda's and committees can significantly affect the outcome and therefore the policy38.

It has just been remarked, that each actor must make an estimate of the utility of certain policy decisions. In principle the individual utility function uk(x) of actor k can assume any form. Here the vector x refers to the quantities xn(k) of the good n, which is owned by k. However, it is more clarifying to assume a simple form. In game theory the form with transferable utility is popular:

(2) uk(x1(k), x2(k), ..., xN(k)) = x1(k) + ωk(x2(k), ..., xN(k))

In the formula 2, ωk is a utility function, which no longer contains x1(k). Apparently the utility uk changes in a linear manner with x1(k). The function is quasi-linear. This has the advantage, that the set of utility possibilities assumes a simple form39. Namely, sum the formula 2 for all K:

(3) Σk=1K uk(x(k)) = x1 + ΣK=1K ωk(x2(k), ..., xN(k))

Since only similar quantities can be added, the formula 2 assumes a cardinal utility. The formulas 2 and 3 imply, that the actors can mutually exchange utility unis, simply by transfering a unit of the good n=1. Therefore this is called a transferable utility. The good n=1 is called the numéraire, as a bearer of utility.

In the right-hand side of the formula 3, x1(k) is no longer explicitly present. It can be interpreted as a constant X, when one is only interested in the variation of u due to the distribution of x1. Now the equation ΣK=1K uk = X is a hyperplane in the K-dimensional u space, with as perpendicular the vector η = (1, 1, ..., 1) 40. This notably also holds for the boundary of the set U of utility possibilities. Then the characteristic function V of C (with c participants) can be represented by the mathematical expression:

(4) V(C) = {u in Rc: Σk in C uk ≤ ν(C)}

In the formula 4, ν(C) is called the value of the coalition41. This shows the advantage of the assumption of transferable utility: the function V, which generates a utility space, is replaced by a function ν(C), which generates a value. Then the game in its characteristic form is (K, ν). And now the core Γ is simply the set of vectors u with Σk in C uk ≥ ν(C) for all C 42. The exchange good n=1 is naturally clearly distinguished from the other benefits n = 2, ..., N, which affect utility in a more complex manner. Usually n=1 is interpreted as money. This is to say, the K actors can compensate each other by means of payments for the possible immaterial concessions, which are made during the negotiations about the policy decision43.

The situation in the game changes, when the utility is transferable. For, then the actors can compensate each other for unfavourable results of votes, by means of a payment with the numéraire good (n=1)44. For instance, consider the table 2, now with the assumption of transferable utility. Then the coalition {1, 2} would be preferred above the outcome β2, when the actor 2 pays a quantity x1 with value in the interval [1, 2] to the actor 1. It may be questioned, whether such transactions are realistic. According to Ordeshook it is strange, that the policy is partly determined by mutual payments between the actors45. When the actors are politicians, then Ordeshook calls this a graft, and therefore objectionable. This may be true for politicians. But when one considers actors in a policy network, then mutual payments may be acceptable.

Compensation could evidently be immaterial. For instance, it could be assumed, that the actors consist of politicians, who promise electoral favours to each other. But then the quasi-linear assumption is dubious. In some cases the application is conceivable, for instance when a coalition distributes the posts of ministers in a cabinet46. Then x1 is the number of posts. So the merit of models with transferable utility is more the theoretical transparency than the similarity with reality47.

When a game has a core, then the actors usually will select their decision here. For, no single actor can improve his outcome by blocking this decision. So this choice has the fairnes of the unavoidable. However, other criteria have also been proposed for calling a decision just. Such claims of justice are naturally normative. They illustrate the institutional approach of policy formation, which downplays rationality and power. Perhaps the most famous proposal for a just decision has been done by L. Shapley. The outcome must be the Shapley value ζ (so actually a vector). The Shapley value is mainly interesting under the assumption of a transferable utility, and therefore this is the starting poiny of the present paragraph48. Shapley makes a proposal for the distribution within the coalition C, but does not want to intervene in the status quo (utility possibilities, available strategies, and the like)49.

Shapley derives his just value from four properties. This is called the axiomatic approach. They are efficiency (Σk in C ζk = ν(C)), symmetry (the outcome for actor k does not change under permutations of actors), linearity in ν(C), and the dummy axiom (ζk=0 for an actor k, who does not add value by himself)50. These axioms are less self-evident than for instance those in the bargaining model of Nash51. Nash derives from these four axioms, that the Shapley value is given by:52

(5) ζk(K, ν) = ΣC in K ((K − c)! × (c − 1)! / K!) × (ν(C) − ν(C\{k}))

In the formula 5, k is an element in the set C, which includes c actors in total. The notation C\{k} represents the set, which is obtained by removing k from C. The k! notation represents the mathematical faculty k × (k-1) × ... × 1. One defines 0!=1. The term ν(C) − ν(C\{k}) expresses the value, which the actor k adds by joining the coalition. This is the marginal contribution of k to C, as it were. The faculties are a weighing factor corresponding to the number of ways (by means of permutations) to form this C. Thus ζk in the formula 5 is an average of all marginal contributions of k.

The Shapley value can be clarified with the following game, for K=3 53. The actors 1 and 2 are agents (U) of policy, and the actor 3 is a developer (O) of policy. According to the figure 1, a design must be followed by its execution, so that only the combination {O, U} has some value, say 1. Suppose that the policy requires just a single agent. Thus one finds the values ν({k}) = ν({1, 2}) = 0, and ν({1, 3}) = ν({2, 3}) = ν({1, 2, 3}) = 1. Thanks to the formula 5 the Shapley value can be computed, namely ζ = (1/6, 1/6, 2/3). Note that the actor 3 is a monopoly, which can play the actors 1 and 2 off against each other54. Therefore the core of the game consists of Γ = {(0, 0, 1)}. Here apparently ζ is not in the core. It is just to such an extent, that it somewhat levels the steep inequality of Γ.

In the parliamentary system, parties form a coalition, which supports its government. The government programme consists of compromises between the parties about the most important subjects. This can be interpreted as an exchange of votes, where the actors grant each other something. In this case, in the parliamentary sessions the parties do not vote according to their true preferences regarding the subjects. The exchange of votes is also useful, when a collective programme is absent, and the members of parliament determine their actions in isolation. Namely, then each politician wants to further decisions, which favour his rank-and-file. Also in this situation the policitians mutually conclude agreements in order to coordinate their votes. They temporarily engage in coalitions. This is called log-rolling, or vote trading. Another conceivable application is the policy formation in a policy network, which decides by means of voting.

| β1= −,− | β2= +,− | β3= −,+ | β4= +,+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| actor 1 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 |

| actor 2 | 0 | 5 | -2 | 3 |

| actor 3 | 0 | -2 | 5 | 3 |

As an illustration the table 3 shows the utility values u of K=3 actors, who must vote about 2 policy proposals55. The interpretation of the table is, that a proposal yields a utility of 7 for a single actor, whereas the costs of 6 are borne by all 3 actors (so u=-2). Each actor promotes a minority interest (otherwise a coalition would be unnecessary). The actor is rent seeking, where he shifts the costs of his preference to the majority56. When the actors vote according to their preference, then both proposals are rejected, so that the outcome is β1. However, the outcome β4 is better for the actors 2 and 3. Therefore it pays for these actors to engage in a voting coalition, where they no longer follow their own preferences. This is an exchange of votes, which is beneficial thanks to the intense preference of the actors 2 and 3 for, respectively, the first and second policy proposal.

The exchange is even socially desirable. Suppose for instance, that the social welfare function is given by W(u) = Σk=13 uk. Then the outcome β4 increases welfare, more than β1, β2 or β3 57. Unfortunately logrolling can also lead to undesirable policies58. For, suppose that in the table 3 each proposal has a utility of 5 for the favoured actor (instead of 7). This is to say, u2=3 for the outcome β2 etcetera. Then one has W = -1, -1 and -2 for respectively β2, β3 and β4. All in all the social costs are larger than the benefits. The proposal unnecessarily increases the state ratio, because actually it must be rejected. Apparently the other actors in the coalition are misled by the high utility (5), compared to the low costs (-2) per actor59. It can only be hoped, that the competition in the bargaining between the actors keeps them alert, and moderates this danger.

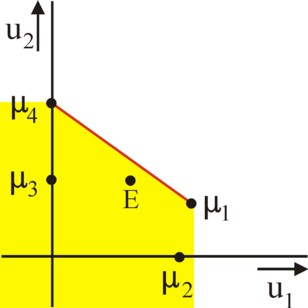

Furthermore, note that at least theoretically situations with exchanges of votes are never stable60. This is illustrated in the table 3, and is shown in the figure 4. First the actors 2 and 3 decide to form a coalition in order to realize β4. But the actor 1 will oppose this by offering a more attractive coalition, say {1, 2} with outcome β2. But next the actor 3 will offer {1, 3} to the actor 1, with outcome β1. And in this situation the coalition {2, 3} is obviously again attractive. Such a sequence is called a voting cycle61. This can be moderated when the actors engage in predictions. For instance, the actor 2 can reject the offer of actor 1, and stick to the outcome β4.

An instability also emerges, when the bundle of proposals is not put to the vote at once, but each proposal is discussed separately. Then it is tempting to defect from the agreed voting behaviour. The actor votes for his own proposal, but against the other ones. Yet in the parliamentary practice it turns out that decisions are fairly stable. Thanks to durable relations the members of parliament have built up trust. They realize, that they need each other also in the future62.

First it must be emphasized, that the concept of utility is essential for the presented social choice theory. One can only decide, when preferences exist. But utility is an elusive and dynamic variable. According as an actor disposes of more means, more can be exchanged, and then the set of utility possibilities of the other actors increases. An actor can derive utility from immaterial variables, such as status, trust, knowledge, or even ideology. And the effort, which is needed in order to acquire the good, again reduces its utility. When all these factors are taken into account, then the social choice theory would be universally applicable. But such a calculation is naturally impossible. Therefore one can only expect realistic results from the social choice theory, when a single cause of utility dominates. Often this utility has a material origin, for instance money.

Furthermore, the mentioned models make assumptions, which are controversial. The actors must dispose of complete information. Moreover, in the previous paragraphs it has usually been assumed, that the actors in a coalition honour their agreements. The enforcement of the "contract" would be automatic. In reality this is evidently all not true, and information can be used as a source of power. The Gazette has already often discussed this theme, usually in the form of the principal-agent problem. Incidentally, the public choice theory offers solutions for this. In specific situations self-enforcing contracts are sought. In coproduction of policy the ownership of the various means and tasks must be distributed wisely among the actors in the network63.

It is worthwhile to integrate the social choice theory in the decision theory of the science of public administration. They can compensate each other's weaknesses. The present paragraph wants to analyze this possibility.

The social choice theory uses a limited number of standard models with a wide applicability, such as the theory of rent seeking. Methodologically it builds on two well-tried and sound approaches, namely game theory and the theory of social exchange64. The social choice theory describes the strategies, which various actors use in their policy network. Their motivation is defined clearly, namely as an (enlightened) self interest. The formation of coalitions can even be modeled in complex situations, such as for decisions about bundles of policy proposals (package deal). Here compromises are concluded, so that the actors vote against their own self interest for some proposals. Situations can also be described, where the actors compensate each other for unfavourable decisions. And finally the morals and institutions are included thanks to the rules of the game and inventions such as the Shapley value65.

The primacy of the self interest fits nicely with societies, consisting of well educated citizens, who embrace individualism. The distribution of power is reflected in the inviolable rules of the game. A previous column has already described the proposal of Buchanan and Tullock to externally impose collective rights in the constitution. According to the social choice theory the policy formulation is devoid of goals, within these legal boundaries66. Only the utilities count, and thus guarantee the support for the policy. So the theory is deductive, and this makes it easily applicable. Notably, games without core show the essence of administrative concepts such as muddling through and the garbage can policy. Then the normal form in game theory is a suited instrument for the analysis of the policy network.

The assumption, that the behaviour of actors is determined by their utility, is a powerful abstraction. But it also conceils certain aspects. For, various factors contribute to the utility, and many of these contributions are difficult to measure. First, the utility of an actor is partly determined by his morals and by the social rules of the game. The social choice theory assumes, that the rules of the game are given in advance. Therefore the institutions and the social morals are an exogenous factor in the models. The morals and institutions become only visible in the utility of the actor, as far as they give him a feeling of satisfaction or displeasure. This reduces morals to a preference. On the other hand, this has the advantage, that the social choice theory is ideologically neutral. The instruments for the execution of the policy also remain undetermined. They are rules of the game and contribute to the utility values of actors, in the form of means and resources.

The actor can only weigh the costs and benefits of a decision, when he can develop rational expectations. Therefore the various probabilities must be known. In reality this is often not the case, because the policy always has unintended side effects67. Furthermore, the compromises in the decision sometimes result in vague formulations of the policy goals. Then the policy only takes shape during the execution68. Also remember the garbage can model. Policy networks try to reduce this uncertainty by mutually sharing information.

Game theory and the social exchange theory do not study the specific nature of the means of power, which are used by the actors69. The struggle to control the agenda is ignored. The social choice theory does study the various institutional forms of policy agenda's70. The social choice theory hardly elaborates on the way, in which networks are coordinated, except for the rules of the game71. It also remains silent about the effect of communication on policies. And finally, boundedly rational behaviour, such as heuristics and roles, actually fit poorly with the actor model of the homo economicus. Then it must be assumed, that a heuristic or role is selected, because it has less transaction costs than rational behaviour.

The present column has made clear, that the social choice models are not capable of accurately describing reality. In fact, this has never been the intention. They merely want to give insight in the general processes, which underlie policy formation. As actor-model the homo economicus is used. This model has proved its value in economics, sociology and social psychology. Incidentally, the model of the homo economicus is usually applied in such a manner, that he acts within the framework of the institutions.

On the other hand, policy analysis often uses narrative models, also in decision theory. Then all factors can be addressed, which are relevant for policies. But this approach also has disadvantages. The analyst may get bogged down in a swamp of details. And the researchers do not have the support of tested standard models. Each researcher develops his own model, so that the debate about the truth is fragmented. This increases the probability, that scientists may succumb to the temptation of propagating morals or an ideology. Here the concept of utility of the social choice theory works like a remedy. because it can often reveal the weak sides of such doctrines.