Figure 1: Colijn cartoon

(1927, Albert Hahn)

Until now the Gazette has not presented a satisfactory connection between the actual description of public management and the various administrative theories. The present column wants to fill this lacuna by presenting two models of the administration, namely the bureaucracy and the new public management (NPM). It turns out that the NPM can solve several deficits of the bureaucracy. Therefore it has become more popular since 1980, and nowadays its instruments are frequently applied in practice.

Since a few years the Gazette studies the recent reforms and innovations in the public administration. Three years ago a column about the policy of the radical centre appeared, also called the Third Way. Notably the developments in Germany and England have been described, during the period between 1995 and 2005. However, an analysis of the ideological foundations was omitted. A year ago the Dutch policy has been described in another column about the Purple cabinets. Incidentally, this text also sketches the New Choice of the New Democrats in America. And in a simultaneously appearing column the radical centre in Germany has again been studied. Yet these studies do not advance the insights. A renewed attempt, which also elaborated on the policies of the Dutch cabinets Lubbers, at least provided some understanding of corporatism. But also here the knowledge of the foundations remained unsatisfactory.

It is strange, that the study of tens of books hardly clarifies the foundations of the modern public administration. But many of these books merely want to describe the history of persons and political processes, and do not aim for an understanding of the public administration. Besides, the ideologies block a sincere analysis. Namely, most of the consulted sources are social-democratic, because precisely in 1995-2005 this ideology rules. However, originally the modernization is started by liberalism (notably the governments of Thatcher and Reagan). This heralded the definitive end of socialism as an ideology. The social-democratic literature has some reservations in admitting its ideological defeat, so that its texts are rather ambiguous and vague1. Although at the time the social-democracy had administrative successes, nowadays it still wrestles with its identity crisis.

It is probably more fruitful to first make an inventory of the foundations of the public administration, and only after this to interpret real life. Since its establisment, the Gazette has analyzed such foundations. Already six years ago a column about the social-democracy described the problem of politically transforming the preferences W(u) of the voters into a set of target functions U(q). Another two years later the new institutional economics (in short NIE) was presented, which analyzes various problematic behaviours, such as rent seeking. The problems of collective property have been discussed, and the costs and benefits of privatization are compared. At the start of 2018 the target functions are again addressed, now in the form of social welfare functions.

Here it always concerns analytical models of political and economic processes. They identify the (probably) decisive factors, which affect the public administration. But they are too abstract and therefore too simple for providing a usable interpretation of reality. They can not generate a theoretical-substantial frame for the political, institutional, sociological and economic columns in the Gazette. The present column makes a new attempt. It again addresses the public administration, but now from a policy-theoretical perspective. In policy analysis the theoretician must leave his ivory tower and test his ideas in a comparison with practical reality.

The focus is on the literature about the new public management (in short NPM). Here management can be interpreted as entrepreneurship in the spirit of NPM. The NPM analyzes political processes with a theory of organizations, which uses abstract models as a tool. Therefore it is the link between the descriptive and the model approach. During the nineties of the last century NPM has become a popular manner for interpreting the practice of public administration. This column takes its contents mainly from the books Public management & administration (in short MA) and New public management (in short PM)2. The ideas in these two books are not all commonly accepted, but your columnist believes that they are clarifying, convincing and defendable.

A clear understanding of new public management requires, that first the old administrative doctrine is described succinctly. During the first half of the nineteenth century the public administration was still often managed by volunteers, or by individuals, who had obtained a concession from the state (MA 18). This system was characterized by arbitrariness and therefore by an inequality of justice (PM 30). According as the middle class became more powerful, the desire for a better system increased. Finally the choice was made to establish a state bureaucracy3. This is also called the civil service. In the analysis officials are usually distinguished from politicians. Although politics leads the bureaucratic administration, it is not a part of it. This is evidently merely an abstract assumption (MA 26). In fact politicians do sometimes receive wages, and then become administrators. Politics and the civil service (as a bureaucracy) need each other.

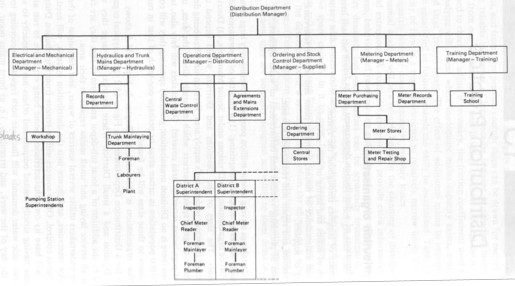

Each organization in the bureaucratic structure has a well-defined task. The task is divided in various subtasks, so that layers of execution are formed with an increasing specialization4. This is a division of labour, where each subtask requires a specialized expertise. The organization is functional (PM 129). The production is planned and hierarchical, where the coordination of the subtasks is realized by means of strict rules and supervision (PM 17)5. The goals at the highest policy level are designed by politicians, namely the representatives of the people (parliament, municipal council) and the chosen top of the administration (government, the mayor and aldermen, B&W). This is the policy formulation. Politics delegates the execution of the goals to professional organizations, which are structured in the way of the described bureaucracy. They must be politically neutral (MA 22).

The organization is hierarchically ordered in such a manner, that efficiency, effectivity and equity (justice) are optimal. For, each worker has an accurately defined task. The conditions of labour are such, that the worker is incited to behave as an (obedient) homo sociologicus. Apparently a century ago the people already understood, that without clever incentives the personal interest would deviate too much from the general interest. First, the hierarchical supervision furthers the desired behaviour. Furthermore the worker has a high job security (usually a job guarantee for life) and a solid pension (MA 150). As long as the worker accurately executes the rules, he is certain of a steady career (MA 23). The sidewise inflow of personnel is discouraged (MA 150).

All this stimulates the worker to behave in a reliable manner and to be loyal to the organization (MA 151). This weakens the incentives to seek rent in the execution of policies. Then the performance of the bureaucracy as a whole becomes stable and predictable (MA 23; PM 18). The rules lead to standardization (MA 28), and are a guarantee for rationality. The resulting activities are more akin to an administration than to management (MA 155). Since the execution proceeds mechanically, the responsibility (accountability) for the policies lies completely with politics (MA 26). Politics realizes its goals by providing the bureaucracy with sufficient means (MA 169; PM 76). This is called input management (PM 141, 151).

The specialized expertise is the hallmark of the bureaucracy. Within the traditional public administration the conviction dominates, that the bureaucracy has a better insight in the social development than others, like interest groups (MA 206)6. Knowledge is a factor, which contributes to the power of the bureaucracy (MA 23). Nevertheless, the public administration itself is not accountable (MA 245). In the European democracy only politics (first of all the concerned minister) is accountable for abuses in the execution of policies, even when it is ignorant about the matter (MA 243)7. This is a problem, because the executing organizations possess more information than politics (PM 20). Thus the bureaucracy can even influence the formulation of policies (goals) (MA 32-33; PM 16, 25). Here the loyal reader recognizes the principal-agent problem.

Management by means of production factors is only justified, as long as the bureaucracy is undisputed the best approach. Actually this is of course an illusion. Already in 1937 the economist Coase states, that efficiency benefits from a good mix of the hierarchy and free markets. The hierarchy is too rigid to adapt to rapid social changes (MA 37; PM 19). Its capacity to learn is weak (MA 37)8. The various policy departments (services) are directed inwardly, and rarely cooperate9. Besides, society becomes more complex (PM 30). During the seventies of the last century the industry already reduces its bureaucracy (MA 38, 48). At the time the public administration has also become inert and too expensive (MA 32, 48; PM 29-30, 34). It does not have incentives to be efficient (MA 61).

Thus the efficiency is completely lost in the endeavour to treat all equally and to be neutral (PM 26)> Everybody has the same claim on bad performances10. The administration becomes a hindrance for social progress, which develops towards pluralism (PM 27-28). Due to the high costs the state claims an ever larger part of national income. During the seventies the state ratio regularly exceeds the 50%, sometimes even amply (MA 86). Working in the public administration also gets a bad reputation on the labour market. It is true that job security is high, but the opportunities to unfold the personal talents are rare (MA 152). Because of all these factors the public administration is reformed during the eighties and nineties by the introduction of instruments, which originate from NPM (MA 44)11.

The new public management (NPM) is a paradigm and a concept (MA 262-263; PM 47). It owes its existence to the new scientific insights, which emerge around 1970, when reality shows the weaknesses of the existing management methods. Scientists make proposals for improving, on the one hand, the functioning of institutions, and on the other hand, entrepreneurship (management) (PM 49). The analysis of the institutions takes the homo economicus as its image of man (MA 10, 40). The public choice theory expresses doubts about the loyalty and dedication of officials with respect to the general interest12. The principal-agent model illustrates the power of officials (MA 12). The theory of the transaction costs shows, that often the hierarchy is not the most efficient form of organization.

The NPM proposes alternatives for the bureaucracy, which take into account these insights. The NPM derives knowledge from management theory, law, policy analysis, and economics (PM 47). Contrary to the traditional paradigm of the bureaucracy, where politics manages only by means of the factor costs (input), the NPM prefers managing the policy results (output, or even outcome) (MA 60; PM 6)13. So the primacy of politics remains intact (PM 71). The political goals must be realized in an efficient and effective manner. Politics selects the instruments of policies by means of a cost-benefit analysis (PM 187). The results are made quantitative by calculating indicators, which are relevant for the stated goals (PM 147). Indicators are obviously indispensable for result management14.

The instruments, which affect the execution, use incentives of competition. They further efficiency, and present choice options to the customers (MA 11). Besides, such instruments increase transparency, because they supply information with regard to the execution. The information is wider than just indicators. Since the performance of the bureaucracy has become discredited, a search for alternative ways to supply public goods and services has started. There is a plea for entrepreneurship in order to make the execution more rational (PM 58, 71, 114). Entrepreneurship is furthered by competition (PM 204). Many of the public goods can simply be exchanged on private markets, possibly restricted by means of regulation (MA 39, 82; PM 66). Both enterprises and non-profit organizations can engage in the production (make-or-buy decision).

The real state enterprises (airline companies, public transport, telephony, waste management, savings banks, shipyards, mining and the like) have been privatized first (MA 94, 240). Ways are proposed to curb the private monopoly, for instance by keeping the network in public ownership (MA 102)15. These tasks are not the responsibility of the state, because the state does not clearly perform them better than the private market (MA 105 and further). But the private market is not the only option. NPM is only interested in the competition, which is present in private markets (PM 204). Competition provides an incentive to perform better (PM 222). Politics can also further entrepreneurship by making organizations more independent (autonomy) (PM 94). They can learn from the experiences in the private sector (PM 59). The aim is to balance supply and demand (PM 89). Therefore, the decentralization of execution is preferred more often than in the past (PM 97).

Politics often manages the execution by means of performance contracts (MA 44; PM 166) or agreements (PM 167). The arena of such performance deals outside of the private market is often called a quasi-market (PM 206, 211). This requires negotiations, among others about the price (PM 102, 168, 178). The management of the executing organizations can determine their own working methods, including the expenditure of the agreed budget (MA 55; PM 99, 160). It distributes its own budget. In this manner NPM widens the separation between financing and execution (PM 106, 178). Then the executive management is responsible for the realized performances. This stimulates management to engage in a more customer-centred approach. An executing organization with satisfied customers increases the probability, that its contract will be renewed. More and more the organization accounts to the customer, and not to the voter (MA 237; PM 98). The customer demands quality, information, and choice (MA 237)16.

Good public services increase the legitimacy of the executing organization (PM 13, 31). The executing entrepreneur must develop his own strategy (towards goals), much more than the traditional bureaucracy (MA 132). This is called strategic management (MA 141 and further). The public administration partly takes over this task from politics, with the approval of both (MA 133). Therefore the direction of the executing agency becomes more publicly visible (MA 207). The agency continuously deliberates with all concerned groups (MA 206, 248). This is essential for performing well. And the agency can increase his power by solliciting support from interest groups (MA 207). Besides, the participation of customers and interest groups has a democratic value in itself (MA 209; PM 55)17. Pressure groups, the media and scientists become partners of the agency (MA 209).

The participation makes the execution more complex, but also creates opportunities for quality (PM 102). The competition between the various interest groups is called pluralism (MA 212). A previous column has shown, that competition can degenerate. The state must take care, that the power struggle between the groups remains fairly balanced (MA 214). The state is a player in the social network, and he can also intervene coercively, when necessary. This is called public governance (MA 77; PM 39). A special form of governance is the public-private partnership (in short PPP; PM 36). In PPP the risks and resposibilities are shared by the partners (PM 217 and further).

Contracting assumes various forms. It can simply be an agreement (PM 172). In any case the agencies must be held accountable for their performances, so that competition is encouraged. For instance, the executing agencies begin to internally and externally pass on the true costs for delivered services (MA 174; PM 167, 206). This stimulates efficiency, and furthers transparency (MA 181). Here the transaction costs must always be included. For instance, the tender for the execution can itself be a costly procedure (MA 179). In the ideal situation all costs are coupled to products (PM 192). In benchmarking the organization compares its performance with those of congeners (PM 210). When such methods are permanently successful, then private markets are not necessary (PM 224)18. The granting of concessions is a temporary privatization (PM 222).

Politics remains responsible for controlling: tender, contracting, decisions, and supervision (PM 112, 177, 185). Notably the fragmented execution forces politics into the role of coordinator (PM 111). Also within organizations the coordination between the functional groups increases. The focus on the customer leads to one-stop-shops, so that the customer contacts are taken up by a single counter (PM 131).

The NPM naturally also changes the position of the personnel in the agencies. The jobs become comparable to those in the private sector (MA 154; PM 246). Incidentally, the activities justify this convergence (MA 154). The career is related to the personal performances (MA 154; PM 248 and further). The traditional bureaucracy does persevere in the formulation of policies, where the administration advises politics (MA 156). Core departments and a small town clerk's office are sufficient (MA 156; PM 20)19. Obviously, a problem for these core organizations is, that they are not incited to be efficient (PM 124).

In conclusion, the paradigm of the new public management clearly has characteristic properties (MA 260; PM 37). Almost all scientists have their own list of NPM elements (MA 51-53; PM 41)20. Your columnist prefers a list, which the authors of the book New Public management have published elsewhere21. It is:

The customer, the personnel and politics benefit from NPM (PM 65). However, the state has historically built up its own administrative structure. Therefore NPM can not assume the same form in all states. There is a path-dependency of the state structure (PM 44)22. Thus each state will make its own selection from the NPM set of goals and policy instruments for the execution of policies (MA 267). The practical diversity is large (PM 47). Besides, internationally there are time differences in the moment of introduction of NPM instruments (MA 265). Often the reforms only start after the emergence of an administrative crisis. The NPM is not a political doctrine, but it does give advices with ideological consequences (MA 269). For instance, it is irreconcilable with socialism (socialization of the whole economy). In this sense it does impose morals (PM 42).