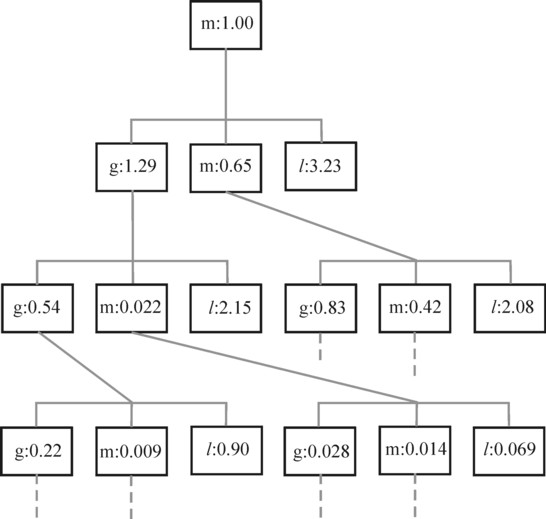

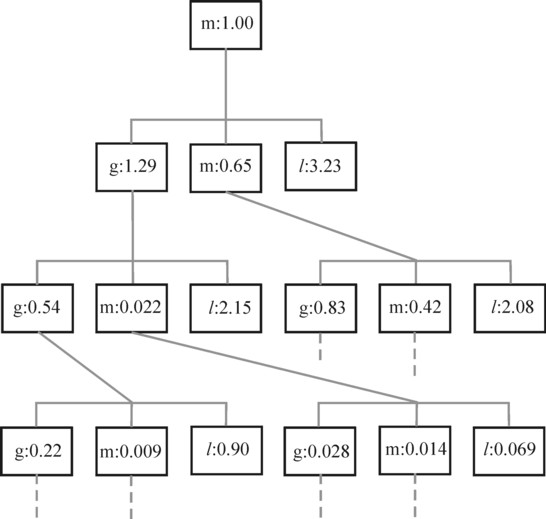

Figure 1: Production layers in the production of metal

--- Numbers are taken from the example

Various preceding columns have presented discussions of production models, that use intertwined matrices (sometimes called Leontief models, input-output tables, or balances). The present column describes methods for the calculation of the material coefficients of the total or full input (in the German language Bedarf, Aufwand) in the production. Besides, a method is presented for the dissection of prices into quantities of dated labour. These methods are useful for the economic planning at the macro level.

In this column several simplifying assumptions are made. The producers dispose of a single existing production technique. The techological progress, and thus the innovation, is ignored. Therefore, the growth due to a rising productivity of labour is ignored. Moreover, the presented calculations are limited to linear production models. Consequently the possible positive effects of scale are ignored. Here a rise of scale will not change any proportion in the production. The common expression for this neutral situation is constant returns to scale.

In fact the column is completely based on the book Vorlesungen zur Theorie der Produktion by the famous economist Luigi L. Pasinetti1. But the motivation to write the column has another origin, namely the many economic works from the former Leninist block. In these states the production models were popular, because they give insight in the functioning of planned economies. At the time the Eastern European governments have invested much in research, that tried to make the models applicable for the economic practice. The column will on several locations refer in footnotes to the Leninist literature, which your columnist has acquired notably from the Berlin second-hand bookshop Helle Panke2.

It is unfortunate that this rich source of literature had been ignored by the west. There are several reasons. First, the free market economy can not be reconciled with a central plan. Incidentally, here the scientific institutes can not even access the information about the production of the enterprises. Second, there was an ideological barrier: all Leninist products were supposed to be inferior. And third, most of the literature was published in the Russian language, which was never popular in the west.

In the column about the intertwined balances the fundamental equation of the neoricardian theory has been defined3

(1) y = (I − A) · Q

Contrary to the mentioned column now the time variable t will be left out, because the present column only considers static situations. The formula 1 is a vector equation in n dimensions, where each dimension corresponds with a branch of economic activity. Each branch generates only a single product. The quantities in the total product are represented by the vector Q. The vector y is the end product, or according to Sraffa the nett product.

The difference term I-A shows that the end product is smaller than the total product. Here I represents the unity matrix, and A is the matrix with elements aij = qij / Qj. The indices i and j lie in the interval 1...n. The symbol qij expresses the quantities of product i that are needed in order to generate a quantity Qj of the product j. The elements of A are called production coefficients in the western states, whereas in the Leninist states they are called the coefficients of the direct material input or the coefficients of the circulating input (in the German language Qj)4.

Apparently in the production coefficients the required quantity qij is reduced to the quantity per unit of j. This is expressed clearly in the formulation ∂qij/∂Qj = aij. Furthermore, note that the index j refers to both the branch and its product. The formula 1 expresses that a part of the total product is consumed by the branches themselves.

If desired the formula 1 can be supplemented by a relation, which describes the connection between the size of the production and the required amount of labour. In vector notation the relation is

(2) L = a · Q

In the formula 2 L is the totally required amount of labour. The right-hand side is the inner product of two vectors. The vector a consists of the components aj = lj / Qj, where lj represents the required quantity of labour in the branch j. In other words, the vector represents the quantity of labour which is required in the branch j in order to generate a unit of the product. The components of a are also called the coefficients of the direct input of labour, or in short the labour coefficients. Together with the production coefficients they form the technical coefficients.

Identify the inverse matrix of I-A by the symbol B. Then the formula 1 can simply be rewritten as

(3) Q = B · y

The elements of B are represented by βij, and they are evidently constants as well. Apparently the coefficient βij expresses the quantity of the product i, which must be generated in total for a unit of the end product j. She can be written by means of mathematics in the form of the partial derivative βij = ∂Qi/∂yj. In other words, she is the totally required quantity of means (in the German language: the Bedarf) for the production of the final consumption. She contains, in addition to the direct material input (the means of production A·Q), also the indirect material input.

In the Leninist states the βij were called the coefficients of the full input5. The formula 3 can be considered to be the foundation for planning, because the plans are commonly based on the end product. The size of the economic system is merely its derivative.

In the matrix theory it can be proven, that the matrix B equals I + A + A2 + A3 + ... 6. Substitution of this power series into the formula 3 yields

(4) Q = y + A · y + A2 · y + ...

The formula 4 is a dissection of the total product Q in such a manner. that the production structure is clearly visible. First the production system must generate the end product y. But this does not suffice. The production of y can only proceed, when a quantity A·y of the means of production is available. That explains the second term in the right-hand side of the formula 4.

Similar arguments will now show, that the means of production A·y can only be available, as long as they have been produced earlier by means of a quantity of means of production A2·y. This is the third term in the right-hand side of the formula 4. The same argument can be repeated in an endless way, which explains the existence of the infinite series in An·y 7.

As an illustration the figure 1 shows a scheme of a number of layers in such a production process. The end product is located at the top of the pyramid (in this case a quantity of 1 ton of metal). Each lower layer represents the production factors, which are needed for the production in the layer above. The dotted lines are vertical production columns, which have been left out. The scheme is taken from the example, which will be discussed at the end of this column8.

The total quantity of labour, which must be expended for the generation of the product, can be calculated simply by means of the row vector v = a · B. The components of the vector are vj = Σi=1n ai × βij. It has been stated previously, that βij represents the required quantity of the means of production i for a unit of end product j. The multiplication with ai transforms the physical quantity of i into the quantity of labour, which is expended in order to generate the quantity of j. In other words, the components vj are the quantities of labour, which are required in order to generate a unit of the end product j.

The components of v are called the vertically integrated labour coefficients. The term vertical expresses, that they are the sum of all labour, which must be expended in that vertical production chain. The sum contains both the indirect labour, which was required to generate the means of production, and the direct labour. In the figure 1 all the bits of labour are indicated in the blocks with l in them. Since labour itself is not produced, the labour block does not have its own column.

The vector v is implicit in the formulas 2 and 3. For the combination of both formulas yields the formula v · y = L. Now note that y/L is simply the real wage wR per unit of labour, at least in the case that the factor labour receives everything, which it has generated as end products. That is to say, wR is the physical wage per unit of labour. Apparently that wage satisfies v · wR = 1. In this situation a unit of labour is paid exactly that, which it has produced, namely 1.

The reader may feel, that the preceding arguments are too abstract. Therefore, in the following paragraph an example is presented, in order to make the matter more appealing and transparent. Anyway, the practical application of the previous formulas cause several problems. In the Leninist books about the planned economy much effort is invested in the analysis of the technical coefficients. For instance, studies are made of the changes in the end resuls, when a coefficient is adjusted9.

In this paragraph the dating in the price system of the production process is studied. Since a year ago the first column about price setting appeared, several columns have elaborated in detail on this theme. For the sake of convenience, the arguments are repeated here, and several insights from the former Leninist states are added. The price formula in its most general form is

(5) pj × Qj = Σi=1n (pi × qij) + Dj

In the formula 5 the dependence on time is ignored, for instance in the case of economic growth. The quantity pi represents the price of the product i, and Dj is the added value in the branch j 10.

The added value supplies the income in order to pay the wages, and to accumulate funds for future investments. Also taxes must be remitted to the state, so that the necessary infrastructure can be maintained at the desired level. In principle the formulas 1 and 5 imply, that the summed added values must satisfy the relation Σj=1n Dj = Σi=1n pi·yi. In other words, the total "income" must equal the value of the total end product11.

However, the reality is different. Both in the planned economy and in the private market economy the price formation of products is a subjective process, which is hardly amenable for a logical analysis. In the planned economy the prices are determined or steered at the central level, so that at least some systematics can be introduced12. This process of price fixing by means of planned value modification has been described in a general manner by a previous column. In particular, it is common to modify the consumer prices (or prices for the final consumption) with regard to the prices for the means of production (the industrial or (in German) Erzeuger prices).

Such a differentiated price system is perhaps unavoidable in practice, but it is hardly accessible for a scientific analysis. And the plan also somewhat differentiated the efficiency r of the invested capital, in accordance with the social interests, that were attached to certain economic activities. Therefore, the central plan usually employs physical intertwined balances, whereas the value balances are merely derived and dependent on the physical ones. The price system was kept constant during the currency of the multi-year plan, because price fluctuations disturb the production.

These are the reasons that the Leninist economists (rightly so or not) have never paid attention to the integral price model. Therefore, in the present paragraph your columnist draws mainly from the neoricardian theory of Sraffa. In that model, which is based on perfect competition, the producer j receives in exchange for his production a yield according to the formula

(6) pj × Qj = (1 + r) × Σi=1n (pi × qij) + w × lj

In the formula 6 w is the wage level. The efficiency r of capital can be interpreted as the profit rate, corresponding to the prevalent social conditions.

The interest must be paid from the profit. When it is supposed that the producers themselves receive an insignificant surplus, then r equals the interest rate. Apparently, together with the efficiency r there are n+2 unknown variables. The calculation of these variables becomes more transparent, when the quantities are removed from the formula 6. The division of the left- and right-hand side by Qj yields

(7) pj = (1 + r) × Σi=1n (pi × aij) + w × aj

The producer j can not solve the formula 7 by himself. The prices for his raw materials and equipment are dictated by the market. The solution is only possible at the macro-economic level, where the formula 7 has the form of a vector:

(8) p = (1 + r) × p · A + w × a

The solution is obviously13

(9) p = w × a · (I − (1 + r) × A)-1

If desired, the wage level can be taken as the numéraire. In that case the prices become relative, namely p/w.

The argument of the formula 4 can be repeated for the price formula 9, in order to make also a decomposition of the price:

(10) p / w = a + a · (1 + r) × A + (1 + r)2 × A2 + a · (1 + r)3 × A3 + ...

The formula 10 can be explained in the same way as the formula 4. The price of a product unit must contain at least the wage sum of the labour, which is expended directly for its generation. That is the first term a·I in the power series. The second term represents the labour, which has been expended in the generation of the used means of production. This is called indirect labour, because it has been done during the previous period Δt. In the same way all following terms can be explained.

The difference with respect to the formula 4 is the term (1+r)n. It takes into account, that capital must yield a revenue. Consider for instance the second term a·A. It has just been stated, that it represents the labour, which has been expended in the previous period Δt. The investor wants to realize an efficiency r on the advanced wage sum, so that in the sale of the end products a·A must be "taxed" with a markup r. The subsequent terms in the power series correspond to even earlier periods, so that a markup is put on the markup14.

The formula 10 shows that the price is composed of contribitions from the direct and indirect labour. Whereas in the formula 4 all layers of production are treated equally, they are clearly dated in the price formula 10. One recognizes in this formula also the complex manner, in which fluctuations of the wage level and of the efficiency influence the prices. For the wages and the efficiency must both be paid from the value of the end product p·y. For instance in case of a falling wage level w room will be created for an increase of the efficiency r. Each term in the power series will show a different response15.

Certainly for the present theme an example will serve to enliven the theory. Again the familiar example of an economy with two branches (n=2) is employed, namely the agriculture (branch 1) and the industry (branch 2). In the agriculture 20 workers (20 units of labour, lg = 20) produce 12 bales of corn (Qg = 12) during a production period. In the industry 10 workers (10 units of labour, lm = 10) produce 3.1 tons of metal (Qm = 3.1) during the same production period. The nett or end product is y = [3, 0.9].

The production technique is fixed by the technical coefficients. The values of those coefficients aij and aj are displayed in the table 1. If desired the reader can check for himself, that the formulas 1 and 2 are satisfied. The reader is reminded once more, that the values represent the direct use of quantities per unit of product during its generation.

| agriculture | industry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| corn | agg=0.4167 | βgg=1.913 | agm=1.290 | βgm=6.956 |

| metal | amg=0.01667 | βmg=0.08989 | amm=0.6452 | βmm=3.145 |

| workers | ag=1.667 | vg=3.479 | am=3.226 | vm=21.74 |

Next the coefficients βij of the total input have been calculated, which together form the matrix B of the formula 3. They express the quantities of means of production, which are needed in total per unit of end product. Their value is the sum of the direct and indirect input. Also the components of the vector v of the vertically integrared labour have been computed. All those values are also included in the table 1. The reader may remember, that the value of the direct input is normalized with respect to the total product, whereas the value of the total (full) input is normalized with respect to the end product16.

For instance in the agriculture 0.4167 bales of corn are needed as a direct means of production in order to generate a single bale of corn in the total product. However, in total 1.913 bales of corn are needed in order to generate that single bale of corn in the end product. Apparently the first branch requires an input of 0.913 bales of corn and 0.08989 tons of metal during the production process of one bale of corn for the end product.

In the same way the industry requires 0.6452 tons of metal as a direct means of production for the generation of a single ton of metal. However, in total 3.145 tons of metal are needed for the generation of that single ton of metal. Apparently, the second branch requires an input of 6.956 bales of corn and 2.145 tons of metal during the production process of one ton of metal for the end product.

Consider again the end product y = [3, 0.9], then the agriculture requires an input of 2.739 bales of corn and 0.2697 tons of metal in the production. The industry requires an input of 6.260 bales of corn and 1.931 tons of metal in the production. In total at the beginning of the next production cycle 9 bales of corn and 2.2 tons of metal are available as means of production17. This is of course also clear from the data in the first sub-paragraph of the present paragraph, when one calculates Q − y.

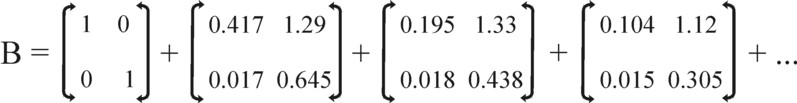

The formulas 3 and 4 show that the matrix B can be rewritten as a power series of the matrix A. The figure 2 shows the form of this decomposition for the present example18. The first term in the power series corresponds to the quantities, that are needed in the end product, and the second term represents the means of production, that generate this end product. The third term represents the generation of the means of production themselves, etcetera.

In the preceding text the figure 1 has already been presented, which is an elaboration of the decomposition in the figure 2. The scheme in the figure 1 is restricted to the branch of industry, and thus concerns the second column in the matrices of the figure 2. The top of the pyramid corresponds to the unity matrix I. Here a ton of metal is located. The production factors, which have been consumed for its production, are shown in the layer below (g = corn, m = metal, l = labour). This layer corresponds to the matrix A.

In the same way the third layer corresponds to the matrix A2. This becomes clear, when all quantities of the production factors in the scheme are added. The result is 0.54 + 0.83 = 1.37 bales of corn, and 0.022 + 0.42 = 0.44 tons of metal. This equals (apart from rounding errors) the second column of A2. The fourth layer in the scheme is not completely displayed, but the reader will understand that it corresponds to A3. Etcetera.

Now consider the price system. The formula 10 shows that the price of a unit of product can be calculated from a power series of (1+r)×A. Incidentally, this expansion in a power series is only possible, as long as the efficiency r is small. In the present example the upper boundary of r is 0.395. A special case is r=0, because then p/w equals v. Then the price is clearly composed of a series of labour values. The first term is the direct labour input, and all subsequent terms represent the indirect labour, which is stored in the means of production.

In the general case with r≠0 the indirect inputs of labour are dated, and the simple summation of labour values is no longer valid. That is to say, in the general case the internal time structure of labour during the complete production process affects the prices19. As an illustration the formula 11 describes the form of pg/w:

(11) pg/w = 1.667 + 0.7484 × (1 + r) + 0.3824 × (1 + r)2 + 0.2210 × (1 + r)3 + ...

The normalized price rises for an increasing r 20.