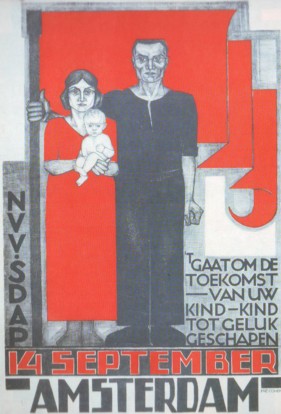

Figure 1: Quartet card

Volwasseneneducatie

Overijssel

The Gazette increasingly pays attention to the national economy. The present column analyzes the theory of the policy of education. Learning theories of adults are discussed, notably the cognitive and humanistic theory. The theory of human capital and the theory of screening are explained. A summary is presented of the recent policy theories with regard to the primary, secondary and tertiary education. Finally, the views of Van Kemenade and Tinbergen are discussed briefly.

Education is one of the pillars of the welfare state. Both the individuals and the state benefit from a highly educated population. The Gazette is evidently mainly interested in the effect of education at the macro level of the economy. The institutional education has three goals1. First, it is indispensable for the development of individuals. Second, education improves the productivity of the individuals. It is an investment in human capital. Moreover, education certifies the made effort to learn with a diploma, which provides useful information on the labour market. And third, the students learn collective morals during their education. They become acquainted with the social institutions. The school is indispensable for the socialization of the individuals. Thus the bonding (cohesion) within the state is strenghtened, so that social capital is accumulated. So the benefits are partially material, and partially immaterial.

The policy must aim at optimizing the supply of education. This is not simple, among others because both the benefits and the costs of education are difficult to measure. Economist do realize since half a century, that knowledge is an important production factor. In a column about innovation the Gazette has already paid attention to models, which describe economic growth as an endogenous process of advancing knowledge. But such models are speculative2. It is undeniable that the traditional compulsory education provides for a sound basis of the educational system. On the other had, there is an increasing expectation, that adults continue or supplement their education. At the same time it is clear, that education leads to high costs. The present column makes a first attempt to present a cost-benefit analysis. Note that the analysis can lead to different conclusions for the individual and society.

Your columnist obtains his technical information about education from the books Volwassenen-educatie (in short VE) and Leren en veranderen bij volwassenen (in short LVV)3. They place the individual in the focus of their analysis of the benefits, and not society. Learning is defined as a process with durable results, so that the individual expands his behavioural potencies (p.80 in VE). Learning is a source of morals and meaning (p.154 in VVL). All things get connected, as it were. Nevertheless, learning can be quite negative, namely when the learned behavioural potencies are an obstacle to efficient and effective actions (p.160, 194 in LVV). The institutional education obviously tries to make learning positive (p.81 in VE). This will only succeed under favourable conditions.

There are roughly ten theories of learning for adults, which each have their specific domain of application. For the present theme notably the cognitive theory and the humanistic theory are relevant4. The cognitive theory assumes the individual mental system, that is to say the frame of reference. This is also called a concept of self (p.88 in VE). The basis of the theory is the methodological individualism. Many individuals learn, because they want to realize a goal, in other words, the motive of learning is extrinsic (p.28, 59 in LVV). Consider for instance the income motive. The individual freedom is restricted by the group morals (p.64, 212 in LVV). The environment also affects the individual by means of cognitive dissonances (p.25, 213 in LVV). Individuals learn by observing the behaviour of others, and by imitating successful behaviour (p.21, 211 in LVV). Therefore learning becomes an evolutionary process.

The humanistic theory assumes, that thanks to human nature the individuals are inwardly motivated (p.83 in VE). The desire to learn is autonomous (p.223 in LVV). People learn for the sake of learning, in other words, the motive to learn is intrinsic (p.28, 59 in LVV). This is apparent from the pyramid of Maslow, who is a founding father of the humanistic theory. Therefore education must not try to form them externally. An environment must simply be created, where the individual can unfold relatively freely. Since the goal of learning remains vague, then the results of learning can not be measured (p.83 in VE). The humanistic theory and the cognitive theory are difficult to reconcile.

The subject-matter of tuition transfers cognitions (knowledge), or skills, or morals, also for adults (p.187 in VE, p.48 in LVV). Here the teacher plays a model role for his pupils (p.51 in LVV). But they are autonomous individuals with their own identity, preferences and responsibility (p.84-86 in VE, p.74, 156 in LVV). They are self-assured. They choose their own goals for learning, and this motivates them (p.87 in VE). Then education must build on the existing mental system. The learning plan or curriculim must be sufficiently flexible in order to allow open learning (p.91 in VE). The pupil must have a say in the subject-matter, and this also holds for the judgement of the progress (p.90-91, 169, 187, 190 in VE). Successful experiences encourage repetitions and imitations (p.60, 137 in LVV). The cognitive theory sees this aspect clearly, whereas the humanistic theory attaches little value to material successes.

Obviously the practice of education is sometimes different. The subject-matter is commonly presented in an abstract manner, because this increases the field of applications. The danger is, that the pupil does not see a relation with reality. He does not succeed in translating knowledge in a personal construction, which has meaning within the personal mental system (p.56 in LVV)5. Furthermore, an open curriculum is risky for the teacher, when he derives his authority mainly from his professional expertise (p.85 in LVV). Book-learning reinforces the passive orientation of the pupils (p.85 in LVV). It also discourages personal planning and evaluation (p.136 in LVV). Then the curriculum remains hidden for the pupils themselves (p.142 in LVV). The pupils must listen and obey, in order to avoid sanctions (p.137 in LVV). They become uncritical followers (p.144 in LVV).

Summarizing, those who want to understand education for adults, must use a mix of theories of learning. The cognitive and humanistic theory differ in their view of man. The social utility of education can be analyzed better with the cognitive theory than with the humanistic theory, because in economic life the extrinsic motive of income dominates. Furthermore, the modern society is pluralistic, so that every (local) group has its own collective morals. Since some morals are better than others, there are good and bad schools. This problem will be discussed again in the following paragraphs. An example: education can teach a passive orientation to pupils. This is the hypothesis of this column: not every education is good, and education is not always good.

This paragraph mainly consults the contents of the books Modern labor economics (in short MLE) and Labor economics (in short LE)6. Nowadays the theoretical school of human capital dominates in the economic analysis of the institutional education. Being educated is interpreted as a decision to invest. The potential student weighs the costs C and benefits B of education (p.281 in MLE). The material costs are the costs of studying, and the time spent on studying, which is lost for earning an income. But there are also immaterial costs, namely the effort of learning. The benefits of education emerge only in the long run, namely better paid jobs, in a challenging and autonomous function. The probability of work pleasure (job satisfaction) during the career increases (p.92 in LE). The humanistic theory also identifies immediate benefits, due to the pleasure of studying (p.285 in MLE).

Suppose for the sake of convenience that the costs C are made at the time t=0. The yearly benefits B(t) are uncertain, and are only received during the course of the working life. Benefits are valued less, according as they are farther in the future. For each year of delay of certain benefits the individual devalues them with a discount factor δ. Obviously δ<1 holds, so that one can write δ = 1/(1+d), where d>0 is the individual discount rate. Let T be the duration (in years) of the career. Then the nett present value of the investment in education equals (p.283 in MLE)

(1) NPV = -C + Σt=1T δt × B(t)

An investment with a size of C only makes sense, as long as the nett present value NPV is larger than zero. According to the formula 1 the discount factor determines, whether the education project at t=0 is profitable. Each individual has unique preferences, and therefore has its own discount factor. However, d(δ) can be transformed into a profit rate r by calculating it for a project, which exactly covers the costs (NPV = 0). The calculated r is called the internal rate of return (in short IRR) of the project. Thanks to this method the various projects can be compared by means of their IRR. Furthermore note, that the costs of the totally received education is determined by the yearly costs of the study and by the number of years of education. At the end of each study year it must again be decided, whether a continued education is profitable. In this manner the marginal costs of education ∂C/∂t are calculated (with t≤0 in the model of formula 1)7.

The presented model gives a simple insight in the decision to (continue to) learn. For instance, some individuals dislike learning, and therefore during the education their yearly costs ∂C/∂t are relatively high. Then the investment in learning will sooner lead to losses (p.284 in MLE). Other individuals are a bit myopic with regard to their future, and therefore have a low discount factor δ. Also for them learning will soon create losses (p.286 in MLE). In other words, this type of individual requires, that the discount rate d of the education is high. Risk averse individuals will invest less in their human capital, because the benefits B(t) are uncertain (p.292 in MLE)8. Levelling of the wages will also discourage the formation of human capital (p.291 in MLE).

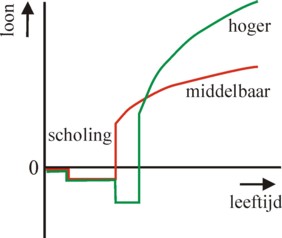

In this argument the immaterial costs and benefits are always taken into account. In general, empirical studies of the effects of education merely measure the income during the career T. Evidently such studies do not elaborate on the individual discount rate d, but on the average profit rate r. According as individuals have learned for a longer period, their income between the age of 25 and 40 increases faster, at least on average. In the United States of America university graduates on average end on double the wage of individuals with merely a secondary education (p.294 in MLE; p.67, 74 in LE). See the figure 2. Partly the rising wages are caused by company trainings and the acquisition of skills (p.74 and further in LE). It turns out that on average the profit rate r (here in the sense of IRR) of education varies around 5-12% (p.304 in MLE; p.96 and further in LE).

Furthermore, the formula 1 shows, that investments in education are less profitable at a later age. For, older individuals have a shorter remaining career T (p.288, 297 in MLE). Moreover, they receive a relatively high wage, which is given up for each year devoted to studying (p.289 in MLE). Older workers are sometimes educated merely in order to replace their outdated knowledge. Apparently human capital also requires replacement investments9.

Until now this column has assumed, that workers become more productive thanks to their learning efforts. This is undoubtedly true for primary education. However, from secondary education onwards it is dubious whether knowledge and skills are really useful for doing a job. Individuals have already developed their own personality from their adolescence onwards. They differ in efficiency, discipline, zeal, creativity, innovation, or responsibility. It is obvious, that precisely the most talented individuals suffer least from the immaterial costs of learning (p.308 in MLE). According to the formula 1, they will learn for longer periods than their less talented contemporaries. Thus engaging in education is a signal of the already internalized individual skills. A column of more than two years ago has explained, that thanks to the certificates of the applicants the enterprises can indeed distinguish between the individual talents.

According to this theory, education is simply an instrument for screening the most talented individuals. This talent has not been created by education, but it is already present in the individual, by its genetic hallmarks and by his early formation, socialization and experiences. So this view deviates from the school of human capital. It has the important consequence, that education must last exactly sufficiently long to fulfil its function as a signal. Therefore less education than is presently common is possibly sufficient. Finally, politics must decide about the investments in secondary and university education (p.311 in MLE; p.80 and further in LE). The costs of over-education lead to a loss of welfare. Therefore the screening theory warns, that not all education is good.

The screening theory clashes with the theory of the education of adults, which has been discussed in the first paragraph. For, certainly the cognitive theory is convinced, that individuals truly learn new useful skills. Yet, on reflection the screening theory is less odd than its appearance suggests. Empirically it has never been proved, that education leads to economically more productive individuals (p.88 in LE). And also the humanistic theory supposes, that talent is intrinsic. Few students complete their professional education with the explicit intent to become more productive. Most want to show, that they are smart. Or they want to distinguish themselves by their diploma10. One must indeed conclude, that an enterprise hires its (young) workers on the basis of their certificates (p.314 in MLE)11. During the application procedure the enterprise does not measure the productivity of the candidate. When workers have proved skills, then the diploma obviously becomes less significant12.

The policy of education must determine the size of the offer of education. Here the profitability, that the investment in education has for the individual and society, must be taken into account. This implies the application of the formula 1. However, this evaluation is very difficult, because various immaterial costs and benefits emerge. For instance, politics must decide, whether investments in shared social morals (knowledge of social institutions) may hurt the economic growth (welfare loss). Etcetera. Actually the state should base its policy on a social welfare function. But in reality this is clearly impossible. Some will even argue, that the material and immaterial factors are mutually incommensurable. The present paragraph will analyze mainly the material profitability, as a first step towards a complete evaluation of costs and benefits.

Again, it has never been proved empirically, that education indeed increases the productivity (p.88 in LE). Partly for this reason the screening theory has been proposed. Nevertheless, it can be concluded, that during the past half of a century the expenditures for education have increased globally13. Apparently, it is generally recognized, that it is desirable to improve the education of the population. Then the question is evidently, which level of education (and with it the size of the budget for education) is optimal for society.

The theory commonly distinguishes between the various human phases of development. Children until the end of the compulsory education (5-16 years) are still insufficiently capable of making decisions about their own education. The parents and the state act as their guardian. The state dominates the parental authority, due to the compulsory education. Social justice requires, that each child obtains equal opportunities to develop autonomously by means of education. Incidentally, this is also desirable for an optimal productivity, because all innate talents must be used optimally. Apparently sometimes morals and efficiency are interwoven14. At the end of the compulsory education there is still the obligation to qualify.

The compulsory education includes the primary and secondary education. After the compulsory education and during adulthood the individuals are considered to be capable of making responsible decision. In particular, during the tertiary (higher) education there is room for free markets. The present column elaborates on these aspects, and the compulsory education and the higher education will be discussed separately. Four books have been consulted thoroughly, namely The economics of the welfare state (in short EW), Économie et finances publiques (in short EF), Economics of the public sector (in short EP), and De prijs van gelijkheid (in short PG)15.

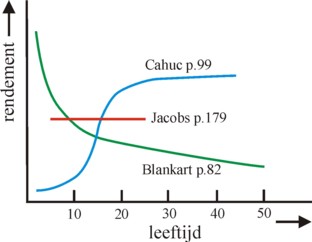

The foundation of the education of individuals is laid during the formation years of todlers. The early socialization is mainly the task of the parents. When during this phase a child develops poorly, then his chances for success in regular education diminish. According to some researchers investments are most profitable during the earliest phases of formation16. Pre-school childcare would be more profitable than the infant school, etcetera. A good preparation is half the work. The effect of the earliest formation is mentioned merely in passing in the consulted books, and it is somewhat beyond the knowledge of your columnist17. However, other researchers state, that most profits are acquired during the subsequent education! Perhaps this is different for each state18. Such differences do not support trust in the practical applicability of these scientific analyses. See the figure 3.

Various books do conclude, that the inflow in the tertiary education is furthered most by investing in the secondary education. This has the result that the students become more positive about continuing their learning, so that the individual discount rate d falls. Here the intervention of the state is acceptable, because by nature highly educated parents attach more value to education than less educated parents (p.313 in EW; p.427 in EP; p.408 in EF; p.181 in PG). This process threatens to thwart the social mobility, and perpetuates (reproduces) the social classes. Therefore the innate talents do not get sufficient opportunities for unfolding19. So qualitatively good education not only encourages better results, but also leads to a better choice of the subsequent education.

Primary education is indispensable for functioning in society, because of skills such as reading, writing, and computing (p.405 in EF). But it is definitely conceivable, that secondary education is already partly a signal to future employers (screening) (zie p.297, 309 in EW). Interest groups and the administrative bureaucracy could unnecessarily increase the offer of education (p.302 in EW). On the other hand, the income tax can discourage attending education, namely when the profit rate r of education is affected (p.194 in PG). See the formula 1, with r substituted for the discount rate d. A falling willingness to continue a study affects the productivity (at least in the theory of human capital), and therefore leads to a welfare loss (p.194 in PG). This is partly a reason for offering secondary education for free (p.197 in PG). The free supply is naturally also logical because of the compulsory education.

Education is not a public good, because it is consumed individually (p.426 in EP). The marginal costs per student of the school are not much smaller than the average costs. However, educations had several positive externalities. First, a continued education leads to a higher income, so that the tax incomes rise (p.298 in EW)20. Besides, it is assumed, that the behaviour of highly educated people is an example for the less educated (p.298 in EW)21. It turns out that a high level of education is favourable for the flexibility of the labour market (p.298 in EW), and it makes the economy more innovative (p.427 in EP; p.184 in PG; p.101 in LE)22. Well educated individuals are relatively healthy, and therefore cause less costs of health care. It is sometimes stated, that this is due to the learned attitude and morals at school (p.406 in EF). Education also lowers unemployment (p.414 in EF; p.68 in LE)23.

Furthermore, schools are a bonding factor at the local level, so that they represent social capital (p.298 in EW; p.427 in EP; p.412 in EF). This argument naturally refers to the moral socialization during education. Thus education also furthers the political functioning, and it stimulates good citizenship (p.410 in EF; p.184 in PG; p.92 in LE). Here it must be noted, that group formation can also be negative, namely when it is too much inwardly directed. This leads to biases and even discrimination. Care must be taken not to segregate education. Nevertheless, in general the positive effects justify the compulsory education, as well as its free supply. This is to say, the costs are covered by taxes.

Since education is a consumer good, it is logical to give a free choice to the parents. A free choice evidently only makes sense, when the schools are allowed to somewhat distinguish themselves, and thus obtain a certain autonomy. Then the schools can mutually compete, or perhaps focus on a certain target group. In principle the primary and secondary education can even be offered by private enterprises (p.428 in EP)24. In such a system the inflow of pupils in the school depends on its educational results. The state pays the school a certain sum for each pupil. In its most pure form the system provides vouchers for education to the parents, as a kind of personal budget (p.314 in EW; p.433 in EF).

However, it is controversial whether the parents must have the right to personally choose a school for their child. For, the free choice can lead to homogeneous schools, so that the children are insufficiently trained to cope with diversity. Then the schools will improve their results by mainly selecting the best pupils (cream skimming) (p.312 in EW). There is a moral hazard, where the most popular schools pick the good risks (p.318 in EW). Difficult pupils are hard to place, and get concentrated in problem-schools (p.435 in EP; p.95 in LE)25. Note that also here the causal relation is controversial. Perhaps the popular schools perform well, because they attract enthusiastic pupils. Thus it is uncertain, whether the quality of education itself leads to better results (p.93 in LE).

A quasi-market, for instance by means of vouchers, must be regulated strictly26. External supervision on quality is needed, because the pupil consumes education only once. The quality can not be established by the market, because then some pupils will become the victim of unsound suppliers (p.303 in EW). Parents are often not capable of judging the quality of the school (p.304 in EW). It has been suggested, that precisely the poorly educated parents will fail here (p.315 in EW; p.433 in EP). Therefore a free choice must be supported by sufficient information. For instance, the schools can be forced to periodically test their pupils, and to publish the results (p.309 in EW).

An important question is the degree of centralization in education. Nowadays there is consensus, that more decentralization is desirable (p.438 in EP). It increases the autonomy and made-to-measure programs in the school. However, the desired equality of opportunities makes some centralization inevitable. This could be done be means of performance indicators. However, the previous column about privatizations has explained, that it is difficult to develop indicators, which indeed result in the desired incentives for the concerned institute (see also p.438 in EP). And some municipalities are simply so poor, that they have little means available for education (p.439 in EP). At least a minimum curriculum must be dictated by the centre - but this again reduces the local say (p.440 in EP).

Strictly speaking, the policy of education must be based on a comparison of the profits of the various investments in education (p.446 in EP). At the beginning of the paragraph it has been stated, that the decision is subjective and therefore political. The choice can be made to maximally support the weakest pupils (p.446 in EP). Then in the end the maximin principle emerges, which has been proposed by Rawls. In practice this is difficult to execute, because the social profits of the various investments in groups of pupils are empirically not well known (p.446 in EP). Generally the conviction does dominate, that it is socially desirable, when individuals can continue to study after the end of the compulsory education, at least as long as they are capable to do so. Often the state subsidizes continued studies (p.317 in EW; p.411 in EF).

The consulted books consider in their discussions of the tertiary education mainly the universities27. Since the sixties the universities have become places of mass education. In some respects, the higher education exhibits the same phenomena as the primary and secondary education, but there are also differences. Thus much information is available about the quality of the various universities, whereas the pupils (students) are more or less capable to make their own conscious choice (p.323, 327 in EW; p.441 in EP). Therefore the offer of education can become more diverse, for instance by means of a modular structure (p.323 in EW). Nevertheless, the children of poor families are still under-represented. This is mainly due to insufficient incentives during their time in the secondary education (p.338 in EW; p.179 in PG)28. Also here it is true, that a good preparation does half the job.

The student invests in himself, because university graduates receive a significantly higher income than less educated people. When the tertiary education would be (almost) free (like during the sixties), then the poor families pay the continued learning of students coming from wealthy origins. This is a regressive system (p.329 in EW; p.441 in EP; p.175 in PG)29. This makes it just to base the payment of the costs on the principle of benefit. This is to say, the students pays a significant tuition. Since also the children of poor families must be able to study, they can contract a loan for their study (p.324 in EW). Such a loan is a levelling of incomes during the course of life, because it is a claim on the later earned high income (p.327 in EW).

It is also an investment, and therefore risky (see the formula 1)30. The risk can be reduced by coupling the manner of repayment to the later earned income (p.326, 330 in EW; p.442 in EP; p.430 in EF). Since commercial banks can not insure this risk, the loans are supplied by the state. Children from poor families could obtain a supplementary scholarship, in order to correct for their high discount rate d (p.327 in EW; p.423 in EF).

Furthermore it is worth mentioning, that the state affects the preparedness to study by imposing taxes, first of all those on income (p.187 and further in PG). Only a poll tax (imposing a lump sum on all incomes, this is to say a single universal payment) would not affect the decision to study. But such a tax would be extremely unfair, and therefore politically impossible. The state must construct the tax system in such a way, that it does not discourage studying. However, this is such a complicated theme, that the discussion will be postponed to a later column in the Gazette. See here and there in PG.

The tertiary education also creates positive external effects. The state must further these by offering subsidies. This is for instance the case for studies, which spread knowledge about the social development, including culture (p.331 in EW; p.412, 422, 430 in EF; p.184 in PG). Consider studies such as Literature or Philosophy. They are actually a public good. Furthermore, the universities obtain income from donations of alumni (graduates) and of rich philantropists (p.424, 430 in EF). In this regard the university is similar to other non-profit organizations.

The debate about decentralization is also relevant for the secondary education. For instance, the state can conclude a contract with the institute of education (p.427 in EF). Or the state delegates the supervision to an independent committee of experts (p.428 in EF). It is interesting that N. Barr propagates a variable tuition, depending on the type of study and the concerned university (p.336, 340 in EW). Moreover, Barr advocates the establishment of elite universities, which can satisfy the needs of the most talented students (p.340 and further in EW). Such a system makes the education more expensive for the students, but it also creates additional funds for education and research.

According to Jacobs education makes social-democracy tick (p.175 in PG). This may well be true, although there are also objections31. In this paragraph the ideas of two leading social-democrats will be discussed, namely Jos van Kemenade and Jan Tinbergen. Two books of these thinkers have been consulted, respectively Geloven in de oogst (in short GO) and Income distribution (in short ID)32.

Van Kemenade emphasizes two functions of education, namely the selection of the future job (p.87, 105, 169 in GO), and the socialization of the pupils (p.18, 84, 87, 105, 126, 176 in GO). He appreciates the school as a local community (p.29). Since individualism in society increases, education must offer more variety, for instance by means of flexible curricula (p.127), brief courses and modular education (p.95, 126, 185). This becomes increasingly simple, when the various institutes of education cooperate. Therefore the present partitions must be removed (p.129). Definitely in the higher education demand steering is indispensable because of the international competition (p.128). Training during the career becomes essential, because knowledge becomes obsolete more and more rapidly (p.127).

One gets the impression, that Van Kemenade prefers the perspective of the screening theory above the theory of human capital. He is clearly worried about the reproduction of the ruling order in education (p.171). The partitions between the institutes of education and the curriculum are still an obstacle for the children from less educated families, who can or want to continue their study (p.172, 177). Van Kemenade cites the French antropologist and neo-marxist P. Bourdieu, who perceives durable social classes (p.175). This could be caused by an unequal distribution of cultural capital. Therefore the mentioned partitions must be removed. All in all the view of Van Kemenade is down-to-earth rational, although he still tends to unreasonably see the "labourers" as victims of a supposed class society. Since then many of his proposals have been realized33.

Tinbergen believes that the spread in attended education is an essential cause of the inequality of incomes. There is notably a scarcity of higher educated people, and therefore these receive a high wage. However, Tinbergen believes that an egalitarian distribution of incomes is desirable. In principle the welfare of the various categories of workers must be equal34. This can be realized by a mix of policy measures. Om the one hand investments can be made in education, so that the scarcity on the labour market is eliminated (p.114, 151 in ID). The policy reduces the profits on investments in education. This affects the supply side of the labour market. On the other hand, the income can be redistributed by means of a progressive income tax (p.110).

Perhaps the scarcity of higher educated people is partly a reflection of the innate capacity to learn within the population (p.121, 148 in ID). Tinbergen supposes, that a tax could be imposed on such innate talents! Even your columnist, who is yet an energetic adherent of psychological research, believes that this is an unrealistic proposal. There are no reliable measurements of talent. And the distinction between innate and learned talent is diffuse. Learning of talent must not be discouraged (p.195 in PG)35. Jacobs warns on p.199 in PG, that high subsidies for universities will lead to over-investments in education and to welfare losses. Moreover, they are regressive, and this increases the inequality (p.199 in PG). On p.200 in PG he prefers the levelling by means of progressive taxes. In general the utopian desire to increase equality (of incomes) has disappeared from science.

Tinbergen remarks, that the economic structure is dynamic, so that the supply side of labour changes. The technical progress creates a growing demand for higher educated persons. Therefore the profitability of higher education will rise. Thus the policy of education and the technical progress become involved in a race, and its effect on the social inequality is not in advance clear (p.156 in ID). Tinbergen, who firmly believes in central planning, advocates to control the technical progress in such a way, that there is no selective scarcity on the labour market (p.156 and further in ID)! Here Tinbergen shows that he is a traditional social-democrat. Nowadays this view is not very popular. The consulted books (EW, EF, EP) all prefer private markets in higher education and in research36.

In conclusion, although the analysis of Tinbergen is fascinating, nowadays his solutions are seen as outdated. Incidentally, in Income distribution he develops an empirical model, which allows to numerically calculate the effect of education on the economy. This demand-supply model will be discussed in a future column.