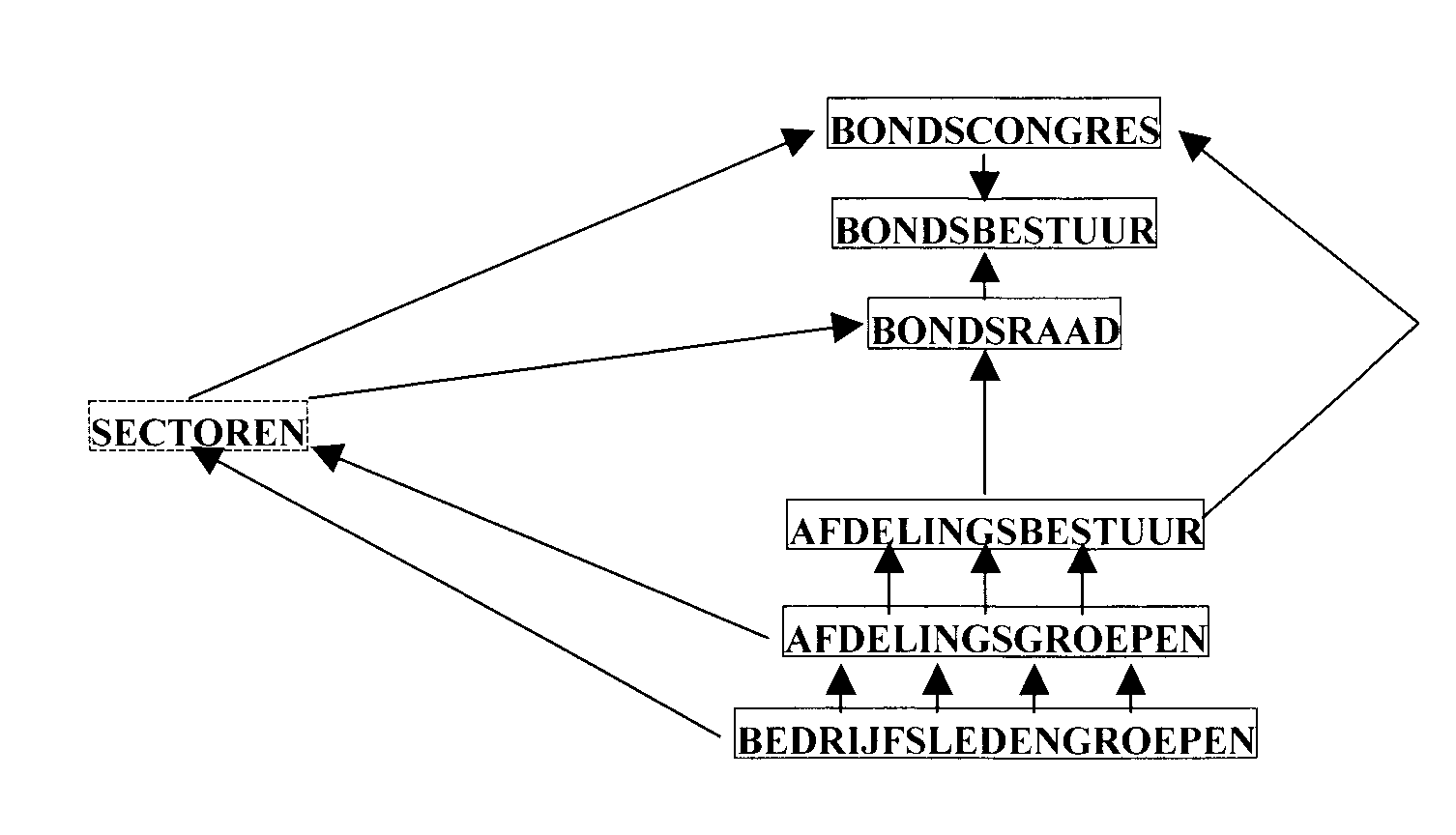

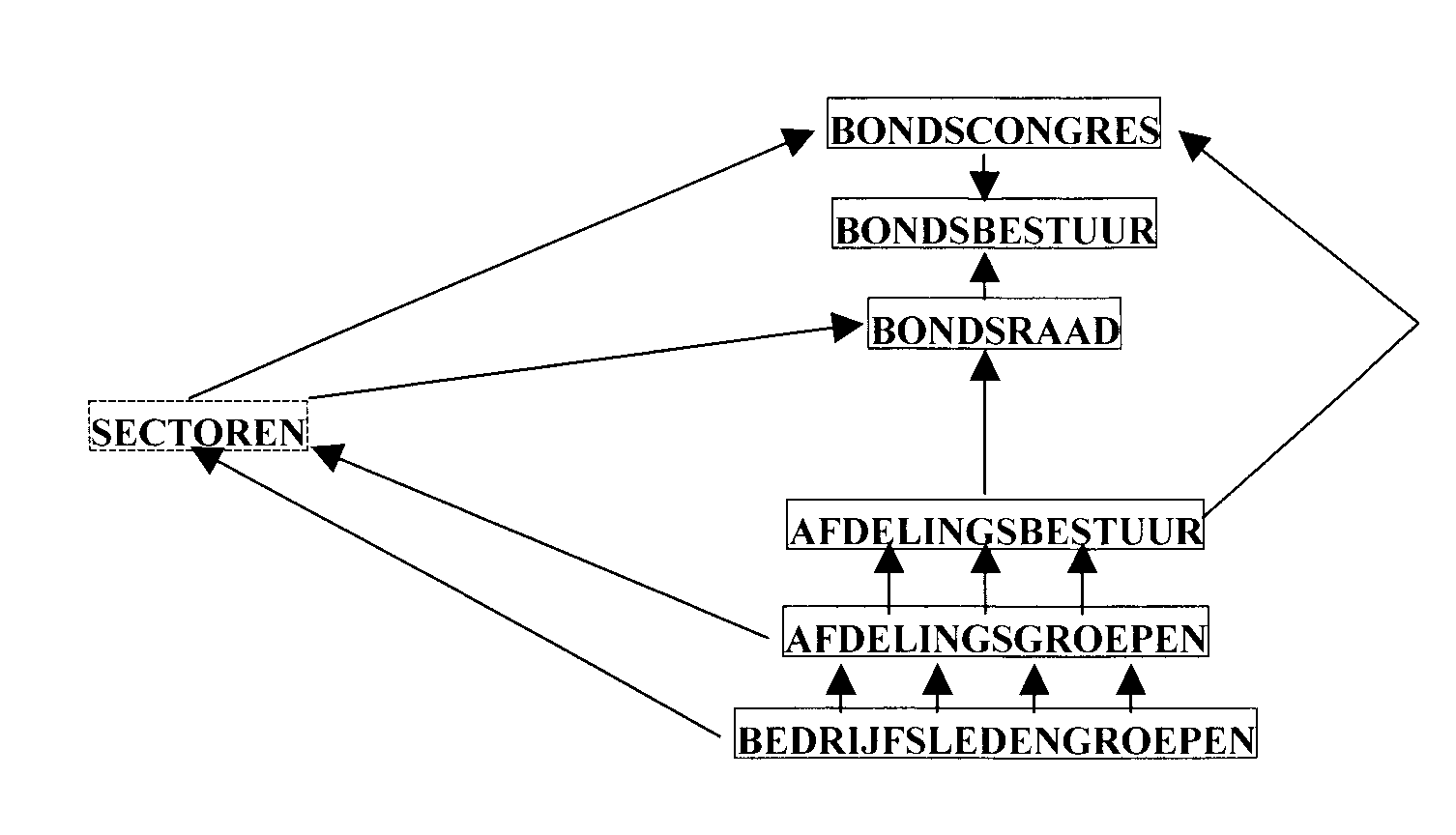

Figure 1: structure of the democracy of the union

The trade union movement is a cartel with a special character. The present column analyzes the influence, that it can exert on the wage level and on the functioning of the enterprises. The democratic structure of a trade union is described. Unfortunately the materialism of trade unions sometimes also causes penal behaviour. Next the mission of the Dutch trade union movement is studied for the postwar period, which is characterized by corporatism and by the controlled-wage policy. At the time the morals serve as a line of action. Nowadays there are theories, that can model the collective bargaining. However, they are difficult to apply to reality.

In 1963 the well-known Dutch economist Jan Pen has written an important book about socio-economical conflicts, namely Harmonie en conflict1. It contains several interesting chapters about the trade union movement. The present paragraph summarizes its essence. In the preceding column Oudegeest yet states, that the trade unions must realize higher wages. However, Pen concludes, that the wages rise naturally, because the factor capital becomes more and more abundant. That increases the labour productivity ap. Besides, the technical progress requires better skills, and thus a better education, which all contributes to the quality of the performed labour. The mass production in capitalism is sometimes called Fordism. The mass consumption is coupled to the names of Kalecki and Keynes, who invented ways to maintain the level of the spending power (the consumptive demand).

Thus in, say, the first half of the twentieth century the part of the wages in the gross domestic product (in short GDP) has increased significantly, in the industrial states from typically 55% to 70%. A cause is the increase of the number of wage-earners, but this can not completely explain the rise. This means that the real wages rise faster than the productivity ap2. In short, the position of the wage-earners improves with respect to other income groups. One may ponder about the extent, in which the trade unions contribute to the rise. For instance, sometimes the trade unions artificially make labour scarce and thus expensive, among others by rejecting and forbidding temporary labour contracts. Then, in economic terms they are a monopolist on the labour market. Indeed the trade unions sometimes abuse their power, but according to Pen these are exceptions.

It has also been said, that the trade union movement hurts the employment, because it pushes up the wage level. That makes the production more expensive, so that the sales decrease. The unions can push up the wages, as soon as the unemployment is low. For, that is also a situation of scarce labour. Besides, during the twentieth century the trade union movement has organized itself, which has increased its power. But Pen believes, that the correlation between the unemployment and the wage level is weak. Namely, the rising wages create additional spending power. The profits do obviously suffer, so that consequentially the investments are less. However, Pen believes that this is not a problem. Besides, many entrepreneurs can include the increased wage costs in their product prices. In that case the profit remains constant, albeit at the cost of more inflation3.

Therefore, some reproach the trade union movement, that it pushes up the inflation. This has serious consequences. For, many social groups are not able to raise their incomes in proportion to the inflation. This does not hurt the high finance, but the small savers and inactive people do suffer. Thus they become the victims. Nevertheless, Pen does not make the trade unions responsible. The rising wages are commonly the result of a true scarcity on the labour market. In that situation the entrepreneurs themselves begin to offer higher wages. The unions must follow by necessity, because they would otherwise lose members. The state is primarily responsible, because it can introduce austerity. The trade union movement is only the cause, when it pushes the wage demands above the market level. And that happens.

Thus, nowadays the state gives a high priority to the stabilization of the prices. Such a low inflation allows the trade unions to restrict their extra wage demands to situations, where the productivity ap rises. For, there is no longer a reason to demand price compensation. Such a bargaining norm is called a wage policy. Incidentally, the trade unions also need to moderate, when they violate this norm with greedy demands. Because such a behaviour increases the unemployment, and therefore reduces the power of the factor labour. The society needs profits and investments in order to make the employment durable. Although the labour market looks a big artificial, yet the law of supply and demand remains valid. For this reason it is doubtful, whether the trade unions can exert a structural influence.

Pen states that they can notably plead in favour of egalitarianism, and equal pay for equal work. The levelling of wages also raises the wage level in the weak and low-productive branches. On the one hand, this gives an incitation to produce more efficiently. On the other hand, thus the needy activities are eliminated definitely. It depends on the social situation, whether this is a desirable development. Under certain circumstances the plea for a differentiation of wages and for more inequality can certainly be justified. This is a fascinating aspect, because it shows the conflicts of interest among the various groups of workers themselves. The economic growth offers a certain room for wages, and for this a distributive code must be found. The operation of markets pushes in the direction of wage differentiation.

It has just been remarked, that the trade union movement prefers egalitarianism. This is notably true for the federations. The most important reason is that this prevents conflicts between the separate unions and between the industrial groups of members. The situation is more complex for the so-called vertical wage differentiation, that is to say, the inequality between various professional groups. Here it is actually desirable, that the wage incites performances. Moreover, some groups need a higher income, for instance in order to pay their own education. On the other hand in any case a dire poverty is unacceptable, because it causes negative "external" effects for society as a whole. Then it is first necessary to attempt to define when life is poverty-stricken. There are studies, that determine a budget for professional groups and their families. This approach is called normative budgeting. However, Pen believes that the method is extremely subjective and impracticable.

Another approach is the work classification. She studies how productive a certain activity actually is. Next a given ap is coupled to a fitting wage. The method is agreable for the trade unions, because it offers an objective foundation for the wage level. The function appraisals are indeed included in collective agreements (in short CAO). Unfortunately the determination of the weighing factors is yet a subjective process. In any case the scale should not conflict too much with the "natural" operation of markets. All in all, Pen is fairly enthusiastic about the function appraisals. However, they are difficult to handle, according as the functions are mutually more different. Your columnist has the impression, that indeed the jobs become increasingly unique. And then only markets can still determine, what the wage must be.

Since Jan Pen wrote his book, the economic knowledge has expanded enormously. The book Labor economics by the French economists P. Cahuc and A. Zylberberg gives a recent survey of the empirical studies concerning the trade union movement4. Firstly, it is striking that the institutions differ in each state. In the Anglosaxon states the collective bargaining of the trade unions is never done at the central level. The coverage of the concluded contracts is too meagre for that, typically 20-40%. On the European continent central bargaining does occur, so that the coverage is 80-90%. Then the contracts are generally binding. Furthermore, since 1980 there is a tendency that the degree of organization (also called the union density) decreases, at least in the western states.

The book Labor economics supports the statements of Pen on several points. The collective bargaining indeed turns out to diminish the inequality of wages, both within the enterprises and between them. Especially the lowest paid jobs benefit from the presence of the trade unions. And the collective bargaining reduces the profits, and thus lowers the level of investments. Furthermore, it has indeed been impossible to detect a clear correlation between the trade unions and employment.

However, the supposition of Pen that the trade union movement raises the productivity ap can not be confirmed. And contrary to the statement of Pen the workers in the organized enterprises do indeed extort higher wages. That is most noticable in the Anglosaxon states, where the trade unions realize approximately 20% higher wages. On the continent the markup due to the trade unions is less, approximately 5%, due to the higher coverage of the contracts, also in the non-organized enterprises.

A study in the essence of trade unions must begin with the structure of a union. The organization of unions varies for the various states and episodes, but nevertheless they maintain generally a striking similarity. The members do not like change. The present paragraph gives a description of a typical structure5. This union X organizes ten branches of activity (sectors), and in addition five sectors of categories, that aim at special target groups (youth, recipients of relief etcetera). In the Netherlands this organizational structure of branches has become common since the Second Worldwar. The union is an association, which is supported by the paid professional organization. Traditionally the activities of the volunteers are coordinated by the local sections of the union. For, at the time the people hardly looked beyond their own residence. This is called the A- or section-line. The work in the enterprises got its own structure much later, and this is now called the B- or enterprise-line.

Thanks to the A- and B-line the union has a matrix structure, with the residence and the branch as the two axes. Each member is incorporated in a local section according to the location of his employer. The section is managed by the local executive, which is composed of democratically elected volunteers. Furthermore, each member is incorporated in the branch, where his employer is active. The union members can organize within their enterprise in a group, the so-called member group of the enterprise (in short BLG). Each BLG can unite with other BLG's in her own branch, within the area of her local section. Thus each branch gets his own group in the section. So in the union X the section has ten of those groups, supplemented by the five target groups. Each group can elect one representative, which serves in the local executive. In this way the section is actually a federation. The structure of the section is shown in the figure 1, and is represented there by the three bottom layers.

The local sections have the task to maintain the emotional band between the members and their union, and preferably also to canvass for new members. They are the place for meetings of members, that want to be active in their union, the so-called cadre members. And they form a connection in the communication channel, that allows the professional organization to share information with their members. Although originally the unions are still managed at the central level, nowadays the communication is organized in a democratic manner. The groups within the local sections discuss matters with regard to their own branch, such as the terms of employment. All groups of the section within a single branch organize in a branch council at the national level. Each group has a say in the branch council by means of her representative (see the left-hand block in the figure 1).

The trade union as a whole is controlled democratically by the members, by means of the yearly union congress. The congress is the highest body of the union. Traditionally the democracy of the union at the national level was delegated exclusively to the local sections, that is to say, the A-line. However, since approximately half a century the B-line has a say on an equal footing about the union policy. Therefore, nowadays the union congress is composed of the representatives of all branch councils, of the target groups, and of the local sections. The congress appoints a central executive of the union, generally for period of four years. The executive is in control of the daily activities of its union. It is obvious that the executive wants to communicate with its members also in the period between two congresses, about various themes that concern the general policy of the union. Therefore a so-called union council is also established, which is much smaller than the congress, and sometimes indeed is called the "little congress". The union council can convene with intervals of several months, or so frequently as is desired, with much lower costs than the congress. At the top of the figure 1 it is shown, that the union executive is placed between the congress and the council.

Most trade unions have joined a national federation of unions. The executive of the federation is the mouthpiece for general socio-economic affairs, for instance towards the government. That position makes the federation executive highly visible. The executives of the connected trade unions are represented in the executive of the federation. Besides, the federation often tries to unite the local sections of the unions at the local level. The federation is democratically legitimized, because she has established a federation council as its own body for members. Nevertheless, the federation must rely strongly on the support and cooperation of the trade unions. Finally, it is worth mentioning, that the sketched structure of a union often has a sleeping or languishing existence, at least at the lowest levels.

A trade union is definitely not an association for charity, and not even an organization of professions. It merely aims at the furthering of the material interests, which now and then can degenerate into greed and pinching. The well-known Belgian socialist Hendrik de Man has expressed this tersely by calling the trade unions a community of fate. The solidarity is enforced from outside. This distinguishes them from the community of ideas, that is bound by shared norms and values.

Historically, especially the socialist trade unions adhere to the ideology of the class struggle, and are implacable towards the industry. And notably this movement is particularly attractive for all kinds of people with a grudge against the realities of life. In unions with a more harmonious view of life the extremism is less terse, but not totally absent. Therefore this paragraph pays attention to the dark sides of the trade union movement. This does not primarily concern the corrupting influence of the unions, for instance when she disguises fraud with benefits or even encourages it. It is true, that lies and a shady egoism are morally objectionable, but at least they commonly lie within the legal limits. However, sometimes a union goes one step further, and tries to reach her goals by means of actions, that are strictly speaking illegal.

She is driven to these actions by her hunger for power. That power is determined by the extent, in which her demands are publicly supported by the workers. A union uses two methods. Firstly, she wants to organize and dominate the workers in an enterprise, and secondly she tries to block the entrance of unorganized workers. Both goals can be realized by the so-called picketers at the gate of the enterprise. However, the propaganda and agitation work up the most radical part of the workers, even to such an extent, that picketing sometimes degenerates into rude intimidation. The Dutch laws against stalking were even introduced for the first time in order to protect the non-strikers against the assaults of their furious colleagues. Whereas picketing is in principle legal, this is not true for the occupation of the factories, and certainly not for keeping the direction as hostages. Yet these two actions also belong to the standard repertoire of many trade unions.

However, this does not end the scale of violence. Namely, especially in the USA some trade unions are originally interwoven with the organized crime. The famous example is the trade union leader Jimmy Hoffa, who finally indeed disappeared from the earth in a mysterious manner6.

Now it will be described how the mission of the trade union movement changes during the two decades immediately after the Second Worldwar. The information is mainly copied from the book De beheerste vakbeweging8. In the previous columns about the public branch-corporations it is sketched that already during the Second Worldwar the Dutch elite prefers a harmonious society. The social-democrats want to stop the class struggle. And the roman-catholics want to order the society by means of corporatism. All believe that at last the new dawn has come. This also holds for the trade union federations within both ideological pillars, the Dutch association of trade unions (in short NVV) and the Catholic labour movement (in short KAB). In the Foundation of labour (in short StAr) and since 1950 also in the Social economic council (in short SER) the top of the trade union movement want to reconstruct the industry, together with the entrepreneurs, in an atmosphere of harmony. The industrial expansion is necessary in order to create sufficient employment9.

The trade unions want to rapidly increase the national welfare, and are willing to moderate their wage demands for this purpose. For the present column the wage policy is important, which is developed during that period, and is unique in Europe. The approach is as follows (see p.26 in Dbv). The Central bureau for statistics (in short CBS) yearly determines the costs of the necessaries of life. The state has established an independent agency, the College of national mediators (in short CvR), which decides about the allowed wage rise. For this the CvR uses a system of function classifications. The CvR consults the StAr and the SER, before a decision is made. Next the StAr is the arena for the wage bargaining, also within the various branches, within the limits that the CvR has imposed. This is actually a harmonious consultation, aimed at maintaining the peace within the industry. The CvR decides about the legitimacy of a collective agreement, and the CvR can also declare that the agreement is generally binding. The SER is merely a consultative council.

Thanks to the control on wages the conjuncture can be curbed. Moreover, it creates room for investments, and furthers the export. The downside is that in 1951 and 1957 the central bodies impose restrictions on the expenditures of the workers. Between 1945 and 1959 the wages of the wage-earners somewhat lag behind the rising welfare. Until 1954 the real wages even stagnate, because the accumulation is preferred. The wage policy is mainly supported by the NVV, because of its ideological views. According to the KAB the policy is temporary, and the Christian national trade association (in short CNV) is even somewhat opposed. The entrepreneurs desire cheap labour, although they also pay black wages, if necessary. Furthermore, the trade unions want to create the financial room for establishing the welfare state. In 1952 the NVV (which is most familiar to your columnist) publishes the report Welvaartsplan, followed in 1957 by Wenkend perspectief. The reports propagate a spiritual emancipation, and arrogantly qualify the call for higher wages as a "narrow materialism".

For the case of the NVV this is amply documented in the book Vakbondswerk moet je leren10. The harmonious spirit is also apparent from the establishment of the works councils (in short OR), in 1950. In this way the old social-democratic and roman-catholic dreams of participation are realized. The institute OR fits well in the ideas about personal development. Henceforth the trade union federations want to make their influence felt by means of the OR, and they make efforts to educate their members for the work in the OR. Remember that at the time many workers have merely an education from the primary school. The need was so pressing, that the federations developed their own educational programs for the formation of the cadre members. In 1947 the NVV establishes the Foundation for school services (p.373 Vmjl). This includes the Worker's evening school, where a bridge is built to the secondary education. The Local cadre school offers secondary education, albeit merely in the economic subjects. Correspondence courses are also offered. Later, according as the Dutch education improves, the school services can concentrate on the union themes.

The confessional federations are also still in the phase of the personal development. The loyal reader remembers from the column about the PBO, that the KAB members automatically join the regional diocesan association. The local sections of the unions have their own priest. He is a spiritual guide for the roman-catholic union cadres, and thus truly participates in the decisions about the union policies. Only in 1964 the diocesan associations are abolished. All in all, at the time the union life is rather paternalistic. The elite demands from her rank and file, that they have a sobre life for the sake of a careless future. The top even condemns labour conflicts and rebellion, because these would conflict with the general interest. In exchange for obedience the rank and file are sure of an almost complete employment, as well as the elimination of extreme poverty.

Until about 1960 the value of products in the Netherlands is party determined on an ethical basis. In the beginning there even is a price control, where subsidies are given on the daily necessaries of life such as milk. The wage control also bases on the morals and ethical principles. Pen just mentioned the instruments, such as the normative budgetting or the work classification. It is true that experts are consulted, among others in the SER, in order to adapt the wage level to the economic situation. But in the end the wages and the prices tend to deviate from the market values. They are ideal and therefore do not lead to an equilibrium. Loyal readers may remember a previous column, where the same problem is observed in the Leninist planned economies. The next paragraph describes, that also in the Netherlands the system turned out to lack durability. The ideal state slowly collapses under the reality of the free markets. There is no alternative for capitalism11.

The wage policy mainly collapses due to its own success. In a situation of full employment the workers naturally demand higher wages, if necessary black. However, there are additional factors, that begin to complicate the control of wages. For instance, the technical development and the globalization make it difficult to yet accurately predict the near future. The collapse occurs between 1959 (formation of the cabinet De Quay) and 1973 (formation of the cabinet Den Uyl). Here again a distinction can be made between two periods. Between 1959 and 1965 attempts are made to include the differentiation in the wage policy. In the second period, since 1965, the situation is complicated further by political turbulences. In the United States of America the black population demands equal rights. This movement for civil rights spreads to Europe. Later she mingles with the peace movement, and obtains the name New Left. The present paragraph is limited to the first period, so until 1965, because the unrest since 1966 is difficult to interpret.

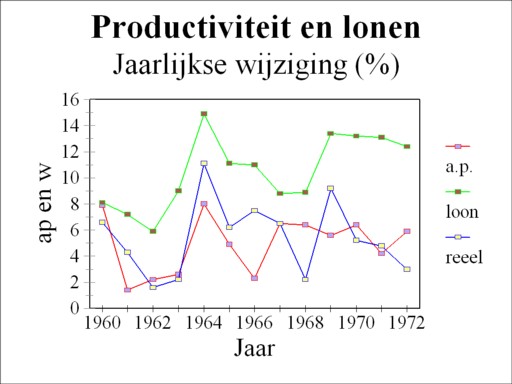

In 1959 the liberal-confessional cabinet De Quay ends the rule of the cabinets by social-democrats and roman-catholics , which lasted for decades12. This increases the willingness of the government to liberalize the wage formation, which initially has the form of wage differentiation. Prospering branches should pay higher wages than withering branches. In practice the full employment blocks the differentiation, because low wages no longer attract workers. In fact the workers have become omnipotent. This is illustrated strikingly in the figure 2, which compares the development of the wages and productivity. The wage growth (green) is structurally higher than the increase of the ap (red). This is even true for the real wage (blue), so after correction for the inflation. During these years the state for ever tries to reconcile these two growth rates. The StAr does cooperate, but the industry simply follows the market wages.

For instance, the state asks the entrepreneurs to at least partly pass on the rising ap by lowering prices (p.72 Dbv). That is certainly wise, but not reconcilable with the scarcity of labour. Therefore the factor labour enriches itself at the cost of the consumers. The attempt by the state fails procedurally due to the technical problems to precisely calculate the ap. The numbers are controversial. Incidentally, the economic prognoses of the Central Planning Bureau (in short CPB) are often questioned by the federations. The reduction of working hours, such as the free saturday in 1961, is introduced earlier than the state wants. Due to the discontent with the existing wage policy the control of the collective agreements for the period 1963-1965 is delegated to the StAr, in other words, to the industry herself. Henceforth the CvR merely supervises at a distance. In this construction the SER is again a consultative body. This is a liberalization, which for the NVV is a change of her old line of action.

The new system of wage formation turns out to function poorly. The labour unrest (strikes etcetera) increases, partly due to Leninist agitation in the enterprises (p.144 Dbv). The year 1963 passes fairly peacefully, but in 1964 a wage explosion occurs (see the figure 2). The SER does not succeed in giving an unanimous advice. The central organizations in the StAr acknowledge, that they can no longer control their rank and file (p.153). This time the state does not intervene, perhaps because he hopes that thus the black wages will be "whitened" (p.147 and further in Dbv). This might ease the economic conjuncture. And indeed the industries are weakened by the wage explosion. Firstly, the international competitive position of the Netherlands worsens. And secondly, the factor labour becomes so expensive, that the entrepreneurs begin to mechanize their production. These are called depth investments (p.148, 160). For the short term the extra investments have the paradoxical result, that the demand for labour still increases!

Unfortunately some of the weaker enterprises collapse, such as those in the textiles branch. Nevertheless for now the employment remains stable, because the state begins to spend more. This leads to overheating in the construction branch. Thus the whole economic structure is affected. And in 1965 the consultations in the StAr stagnate completely, so that in fact the state is forced to intervene and mediate all the time. Under these circumstances the industry is simply not able to internally coordinate herself. Especially the central organizations are shocked, that the electronics giant Philips agrees to a collective agreement, without consultation, that contains an automatic price indexation, and moreover an additional reduction of working hours. The weaker branches actually can not imitate this. Nevertheless, all other collective agreements also begin to include the price compensation (p.188, 209). The first misery already becomes apparent, because in 1964 the balance of payments has a deficit.

Thus the liberalization leads to a decrease in power of the central organizations. Henceforth the collective bargaining shifts to the level of the branches. The economic life toughens, so that backward branches can no longer survive, and become the victim of what the economist Schumpeter calls the creative destruction. On p.408 Vmjl it is concluded, that due to the collapse of the central wage policy the unions are forced to become more active in the enterprises. Therefore from 1959 onwards the unions develop the company action, in order to be present in the enterprises beside the works councils (OR). The union members are encouraged to form a member group in the company (BLG). That does not really happen spontaneously, so that the unions must send organizers in the enterprises. Thus the mentioned B-line is created in the unions. This also affects the OR, where henceforth the union members form their own fraction.

After two decades of guided wage policy the transformation to the free wage formation occurs in shocks. In 1964 the workers get the impression, that anything goes. The New Left movement will further increase the confusion. She is mainly popular within the then youth, and contains many emotional and irrational elements. The previous generations observe her with dislike, and sometimes with horror. Nevertheless, even they can not escape completely from the hysteria. In the Netherlands the derailment is worse than elsewhere in Europe. Henceforth the social-democracy prefers polarization. Her demand-side policy becomes a part of the problem, and not of the solution. The figure 2 shows, that the workers and their unions are no longer capable of making realistic wage demands. From the seventies onwards the economy can no longer support the excessive collective agreements, so that a huge unemployment is created. Then the statement of Pen, that there is an effect of spending power, is no longer relevant. Your columnist will discuss this situation in detail in a following contribution.

Collective bargaining about the wage

To be honest, in practice the existing models of trade unions are not very useful. On the other hand, a model is capable of presenting a simple picture of reality, and that has advantages, certainly for analyzing the essence of the trade union movement. And finally, the models have a divine beauty, which attracts at least your columnist. Why is reality so ugly? Thus here a model and dreamworld is presented of a colllective agreement (CAO) between a union and an enterprise. The model is copied from the profound book Labor economics by the French economists P. Cahuc and A. Zylberberg13.

The model begins with stating the goals, that the two negotiators have. The enterprise wants to maximize its profit Π. Suppose that it hires L workers for a wage w, and that those workers generate a product Q(L). Then the profit is the difference between the sales and the wage sum, namely

(1) Π(L) = Q(L) − w × L

The goal of the trade union is somewhat more complicated. Suppose that all union members have approximately the same preferences. An individual income y gives them a utility u(y). Now suppose that the union merely bargains for a high wage w, and not for employment L. The latter is determined by the enterprise, which thus has the right to manage. Suppose that the union has N members. In other words, a fraction λ=L/N of the members gets a job from the enterprise. The remainder of the members is unemployed, and obtains a benefit x from the state. Obviously, x is less than w. Then the satisfaction of the union members is represented by

(2a) U = λ × u(w) + (1 − λ) × u(x) that is to say

(2b) N × U = L × (u(w) − u(x)) + N × u(x)

For the sake of convenience it is assumed, that during the bargaining the union tries to maximize the total utility U (or N×U) of its members. The members will certainly obtain a benefit, so that the maximization merely concerns the first term on the right-hand side of the formula 2b. Thus it seems reasonable to represent the CAO bargaining by the expression

(3) choose from all w the one, that maximizes the variable ψ = Π1-α × (L × (u(w) − u(x)))α

In the formula 3, α is a measure of the power of the union. For, when α=0, then only the profit is relevant, and the preference of the union is irrelevant. And when α=1, then the profit is totally unimportant. For intermediate values of α the interests of the enterprise and the union are both considered. The problem can also be expressed as the condition ∂ψ/∂w = 0 for the optimum. The result is called the general Nash solution, in honour of the mathematician John Nash.

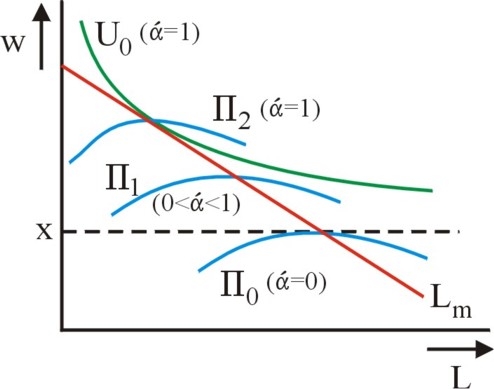

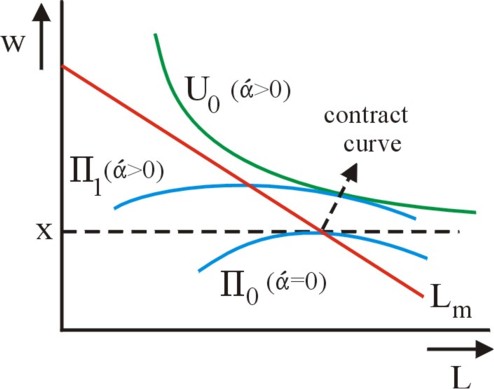

Readers who remember the Edgeworth box, may understand that it makes sense to depict the preference curves of the negotiators in the figure 3. The Edgeworth box also describes a bilateral negotiation. The preference curve for the enterprise has the shape of the iso-profit curves Π = constant. That is to say, on such an iso-profit curve one has ∂Π/∂L = 0. Here the assumption is common, that the output Q increases as a function of L, but at a decreasing rate. Mathematically, this is ∂Q/∂L > 0 and ∂2Q/∂L2 < 0. This is called a concave behaviour of Q(L). The marginal product ∂Q/∂L decreases. Due to the maximization of the profit the enterprise keeps hiring extra workers, until ∂Q/∂L = w holds. This point is L=Lm. For, at a still larger L the extra hired workers would produce less value than their wage w.

Thus the (inverse) demand curve w(Lm) of the enterprise can be sketched, and that is done in the figure 3 (red). It is falling, as is common for demand curves. It can easily be shown, that the iso-profit curve (blue) is horizontal on the demand curve, and rises at the left-hand side and falls at the right-hand side. Moreover, it is concave14. According as one moves to the right on the demand curve, the profit will increase. In order to understand that, consider a constant wage w. Then one has ∂Π/∂L = ∂Q/∂L − w, and that difference is positive at the left-hand side of the demand curve. In short, during a movement to the right iso-profit curves with an increasing constant profit are passed. That is shown in the figure 3.

The iso-utility curve (also called indifference curve) of the trade unions has the form L × (u(w) − u(x)) = constant. First, note that for w≤x no member will be willing to work. The assumption is common, that the utility u(y) increases as a function of y, but at a decreasing rate. Mathematically this is ∂u/∂w > 0 and ∂2u/∂w2 < 0. This is called a concave behaviour of u(w). The marginal utility ∂u/∂w decreases. It can easily be shown, that the iso-utility curve falls and moreover is convex15. The trade union will choose the iso-utility curve with the highest utility value, that is still allowed by the enterprise. The utility will increase, according as one moves to the right. In order to see this, consider a constant wage w. Then U increases with L. Therefore the optimal iso-utility curve of the trade union will be tangent to the demand curve w(Lm), as in the figure 3 (green). There w=wo is clearly larger than x.

Bargaining about the wage and employment

The described model is instructive for several reasons. Firstly, in the Edgeworth box the so-called Pareto optimal solution is sought, where the iso-utility curves of the negotiators touch each other. However, in the optimal solution wo of the present problem (see the figure 3) the iso-utility curve and the iso-profit curve are not tangent to each other. The reason is that the enterprise unilaterally determines Lm. When L would also be included in the bargaining, then a better result could be obtained. Secondly, the presented argument is based on a constant value of α. When the trade union has little power, then the enterprise will lower the wage to close to x. According as the power of the union increases, she will commonly demand a higher wage than x. Then, due to the demand curve the employment Lm diminishes. The union creates unemployment.

Apparently a better bargaining result can be obtained, when a decision about the wage and employment is made as a package deal. Then the enterprise must share the right to manage with the union. Now the bargaining about the collective agreement changes somewhat, in comparison with the formula 3:

(4) choose from all w and L those, that yield the maximum of the variable ψ = Π1-α × (L × (u(w) − u(x)))α

In this case the general Nash solution results from an optimization in two dimensions, namely ∂ψ/∂w = 0 and ∂ψ/∂L = 0. These two equations allow to derive a relation between w and L in a straightforward manner, namely16

(5) w − (u(w) − u(x)) / (∂u/∂w) = ∂Q/∂L

The formula 5 is intriguing, because she describes w(L) independently of the exponent α. This relation is called the contract curve, analogous to the Edgeworth box. One point on the contract curve is already known, namely the point for α=0. Then the enterprise is omnipotent, and will choose w=x. That is the point x = ∂Q/∂L, and is located on the demand curve. See the figure 3 or the figure 4.

Next the complete behaviour of the contract curve deserves attention. Again differentiate the formula 4 with respect to L, where how w depends directly on L, then the result is17

(6) ∂w/∂L = (∂2Q/∂L2) × ∂u/∂w / ((w − ∂Q/∂L) × ∂2u/∂w2)

Under the made assumptions about the derivatives of Q and u the slope ∂w/∂L of the contract curve is positive. The curve goes to the upper right. The figure 4 depicts for an arbitrary positive α, what now will be the agreement between the enterprise and the union. It shows that here the employment Lm is higher than the demand curve would suggest. That is to say, w > ∂Q/∂L. The reason is that in exchange for that employment the union accepts a somewhat lower wage than is possible in the case of some unemployment.

In Labor economics many more collective agreements are modelled. For instance, on p.399 and further the case is analyzed, that the union bargains about the wage w and the compensation b for dismissal. It turns out, that the union will choose b in such a manner, that the unemployed are fully compensated for their loss of wage. In other words, it demands w = b+x. Then the employment is otherwise irrelevant for the union, and the iso-utility curves U(L) = constant are horizontal. The profit of the enterprise becomes Π = Q(L) − w×L − (N-L)×b = Q(L) − L×x − N×b. When the enterprise is omnipotent (α=0), then it chooses Lm on the demand curve at w=x. Then b=0 holds. Moreover the iso-utility curve and the iso-profit curve are tangent, so that Pareto optimality is realized. When the union also disposes of some power, then b>0 holds. However, the enterprise has no reason to change Lm, so that the contract curve is a vertical line.

In Labor economics several other strategies of bargaining are also studied. The possibilities are only limited by the phantasy of the model-developer. In itself the performances of creative thinking are impressive. However, again and again the arguments are based on analogies with the Edgeworth Box, such as occur in the discussed cases. This does not increase the relevancy for practical situations. In principle such models can be applied in two ways. Firstly, they provide a frame of thought for the trade union movement. However, they are too primitive for that. Secondly, the descriptions can be tested empirically by a comparison with reality. For instance, intuitively one is inclined to model the controlled wage policy with bargaining about wages and employment. However, according to p.427 and further in Labor economics such analyses turn out to be inconclusive. Therefore your columnist will halt his elaboration. An analysis must not (further) end in autism.

It turns out that the trade union movement does exert some influence on the economy. It stimulates the increase of wages, notably those of the lowest incomes. The downside is that it discourages the willingness of the industries to invest. Furthermore, the unions bring an element of democracy in the economy, and they contribute to the participation of the workers in the enterprises. But it can also degenerate in breaking the law and in organized crime. The present column analyzes the mission of the Dutch trade union movement in the post-war period. Originally it supports the formation of the welfare state. Here an order of labour is established, with works councils in the enterprises, and with the SER as the national council. The order is very effective in combatting the unemployment, which is historically low during that period.

Unfortunately this period has the drawback, that the state dictates the wage level at the central level. For the sake of employment the investments get the highest priority, so that the workers benefit merely moderately from the growing richess. And the new generations of workers have never experienced the misery of unemployment. They simply demand more income, and the entrepreneurs give in. Thus during the sixties this artificial system of planned prices and wage collapses. Then the trade unions must revise their constructive attitude, and they must abandon the old ideal of harmony. A more militant attitude is required, where the material interests are dominant. Unfortunately, in this respect the unions are not yet very skilled, so that they worsen the conflict and create unnecessary unrest. The new position leaves little room for morals and for spiritual emancipation. In view of this development it may even be wondered, whether full employment is perhaps an utopia.

Nowadays there are theoretical models of bargaining, that can be applied to the consultations with regard to collective agreements. In principle these can provide insight in the strategy of the negotiators, and in the consequences of their actions. However, the reality is so complex, that for the moment the models are not yet really helpful.